Amanda Hansen is president of AdvancedMD of South Jordan, UT.

Tell me about yourself and the company.

I started in the position of president of AdvancedMD in June. It represents my 15th role within the organization over the past 13 years. AdvancedMD provides integrated workflow solutions and services to more than 35,000 physicians and providers in the ambulatory market.

How is that market changing?

We are in a replacement market. We sign a couple of hundred clients per month. The new clients we’re signing are on their second or their third EHR, so they are much more selective. Where historically with EHR it was about meeting regulation and Meaningful Use and driving towards that compliance, now it’s more about usability and workflow. Doctors don’t want a solution that is going to interrupt their workflow and add significant labor and administrative work on the back end.

The need for systems to be integrated and fully connected, that all-in-one, has definitely evolved over the past several years. Specialty-specific clinical records are more prevalent within certain subsets. You get a lot of benefit from having everything connected and working well together.

Is it fair for clinicians to say that the EHR causes burnout?

I do think it’s fair. It is necessary to have EHRs and the data structure and the storage of the information. Hopefully over time we’ll be driving more towards a patient-controlled health record in addition to the clinical records from the physician, and having those work in tandem.

But when you look at the demographic in healthcare, somewhere around 50 to 55% of physicians are over 50 years old. In that segment, it has driven some degree of burnout. The millennial generation, the generation that is rising now, grew up with all this technology at their fingertips, so those types of physicians and providers are excited about the technology. I think it’s more of a generational issue than additional work that has driven burnout.

How are consumer expectations changing with regard to how technology can allow them to interact with their providers in ways that are convenient for them?

We spend a lot of time thinking about this and building strategies. The consumerism of healthcare is here to stay. I’m the perfect demographic to talk about it. I don’t have a primary care physician. My husband and I have three kids and we have an established pediatrician that we go to. But if I get sick, I go to urgent care. I want the same thing. I want an app that I can use. I want to do telehealth or do a telemedicine visit. I want that immediate gratification, that instantaneous response and result. In the healthcare IT space specifically, vendors have to put more resources on having those mobile applications.

Even at AdvancedMD, historically we’ve focused on patient engagement. But the patient engagement we focused on was more driven about how to help physicians engage with their patients, not to help patients engage with their physicians. We need to flip the switch. It has to be patient centralized, where everything drives from that patient and how they interact with their doctors.

With my pediatrician for my kids, we got a patient portal login. We never used it because it was really complicated. We couldn’t remember it. It was dual authentication, just very complicated. Whereas if I get a simple text message that says, go ahead and fill out this consent form and confirm your visit, I’m much more likely to do that than I am to remember some login. It puts pressure on the vendors to make sure that they’re delivering technology in a way that patients want to consume it.

How should interoperability work optimally when a patient’s records are scattered over multiple providers and there’s no PCP to collect and manage all their information in one place?

This is a huge opportunity. This is the secret sauce to making healthcare IT great, being able to have that interoperability and the connectivity. To make it successful, it has to shift from a clinical record from the physician to a clinical record from the physician that the patient can take with them always. This is something that I’m passionate about.

My dad was a type1 diabetic. He got diabetes when he was 20 months old. He passed away about two and a half years ago after two kidney transplants, two pancreas transplants, thousands of dialysis appointments, and a complete loss of vision. He was a modern day health miracle in many ways. He passed away when he was 60. It’s important to me because my mom would take him to doctor’s appointments and she would literally have to bring a binder of his health information with her everywhere they went. It had the prescription history, his conditions, his ailments, the procedures that had been done. It limited the ability of his physicians – specialists, primary care, mental health, behavioral health — to focus on his care at that moment because they were so focused on what had happened historically.

With FHIR and all the standards that are coming out in interoperability and accessibility of information, it really needs to be a record that is controlled by the patient. It doesn’t mean the patient is the only person inputting information we want. There’s a reason doctors go to medical school. We want it to have that flavor and we want it to be certified in the right way, but the patient should be able to take that information with them. What’s missing in healthcare IT is that patient. Companies are trying to address it, like Apple with the Apple Health Records app, and if you’re on an Epic system, you can get your medical record history. It’s something to assemble all of those records into one place that the patient can take with them

Why hasn’t the Health Record Bank concept taken hold?

There could potentially be a role for it. No one cares about a patient’s health as much as that patient. It is like your job, where nobody cares about your career or your progression at an organization more than you do. You have to own that.

Ideally, that the patient would have access to all of their own information and they could carry it with them and be the quarterback for themselves. Some people are in a situation where they can’t do that, and then their caretaker, spouse, family, or loved ones can help drive that. I really believe that it should be patient centralized, because we care about our own health more than any physician or provider is going to.

What is the mechanism of that patient carrying their data around?

That’s the mystery that that we all need to solve. It goes back to your earlier question, which is, can you have some sort of health data bank? We believe in big data. The challenge that we have had with big data so far is it has helped us to understand risk profiles of patients and to segment different patient bases, but it doesn’t create the action plan. If the information can be assimilated, whether it’s through a data bank or something else, that’s great. But the missing link has been what’s done with the information.

We know that 20% of our patient population has a high risk for adult onset diabetes, but outside of that, there’s not anything to link to what those next steps are. It’s tying that data into proactive tools, like our HealthWatcher solution that automates some of that process.

There are hundreds of EHR vendors and healthcare IT solutions. Unless we have some sort of universal health plan where there is only one vendor, then that can’t be the keeper of everything. We have to rely on something else, whether it’s the patient to control their own fate or if there’s some sort of health data bank. But we need to make sure that whatever information is assimilated, that there are action items and automated processes that happen as a result of the information. That’s the missing piece.

Are EHR vendors backing away from offering revenue cycle management services?

There is high demand for revenue cycle management, especially with the increasing complexity of getting reimbursed. Regulation is consistently changing and it makes it more and more challenging for doctors to get paid for the work that they do.

At AdvancedMD, we’ve seen a big influx in our revenue cycle management demand. Kareo recently divested their revenue cycle management business. I don’t believe that was for lack of demand. It seemed that it was more about the financial profile of the organization, where revenue cycle management is a more expensive business. It’s lower margin. With the exception of Kareo, the main vendors that we see day in and day out all have a revenue cycle management offering.

It has helped that providers and physicians want choice. If they want to do their billing themselves, they can use the software. If they want to have someone else do it, we have billing partners, and then we also have our own revenue cycle management division.

What was the strategy behind payments technology vendor Global Payments acquiring AdvancedMD in 2018?

Global Payments is focused on integrated payment solutions. The philosophy is that if they own software companies that have payments integrated within them, customers will be less likely to switch out their payment vendor for an alternative solution. They have, I think, 10 software companies in multiple verticals. Healthcare is a strong vertical, making up almost 20% of the opportunity in the US. We were their first effort in healthcare to have the integrated payment experience.

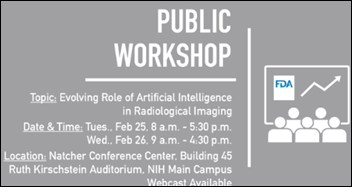

How do companies build a development schedule around technologies such as AI and voice-powered user interfaces that may be at various points on the hype cycle?

It’s always a balance. Technologists always want to work on the latest, greatest, really cool things. Sometimes those really cool things end up not being practical, or they aren’t something that’s even needed. A customer would rather you move a button or decrease the number of clicks to do a step in their workflow process. You see that more with startup organizations, where they are developing things that they think are really cool and revolutionary and then the adoption becomes much more of a challenge.

We experienced that historically with a couple of solutions that we put out. One of those was a benchmarking solution that we felt really excited about, paired with our analytics solution. What we quickly learned is that 70% of our client base is practices of fewer than five providers, independent practices, and they didn’t really care — even in a really cool way — to benchmark themselves against their competitors.

The most important thing that companies can do is to make sure that they keep the voice of the customer at the forefront. Not only do market research, but solicit those clients, internal and external, to help drive their roadmaps and make decisions on what to invest in and what to build.

What lessons have you learned in being promoted many times within one company instead of following the conventional wisdom that you have to move out to move up?

I’ve had a lot of friends come and go at this organization since I’ve been here. I can’t point to any of them and say that they are in a better position, or better off than I am, for having worked through the inner workings of an organization to drive my way to the position that I’m in today.

The biggest thing that I’ve learned is that moving ahead requires taking the jobs that no one wants to do. I’m sure that physicians, providers, and others in the healthcare space understand that sentiment as well. Sometimes it’s not the glamorous things. Sometimes it’s the ones that seem extremely challenging and difficult, but that propel you forward.

We have a great team assembled at AdvancedMD. I am extremely grateful and humbled for all of the people that I’ve been able to work with in my 13 1/2 years at this company. Nowadays, especially, you don’t see a lot of people who are fiercely loyal in sticking with an organization. It requires your own drive and will to do it. It also requires having mentors and advocates who look for opportunities for you. Lastly, it requires raising your hand to do the jobs that that may seem impossible at the time, but they’re not. Anything is possible.

Do you have any final thoughts?

We are excited and enthused about the opportunity to help propel the consumerization of healthcare forward, focusing on flipping the switch and with the patient being central to patient engagement rather than the physician. That’s through mobile applications and various programs to engage patients to play a more active role in their healthcare experience.

‘

‘

Look, I want to support the author's message, but something is holding me back. Mr. Devarakonda hasn't said anything that…