Peter Bonis, MD is chief medical officer of Wolters Kluwer Health and an adjunct professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine.

Tell me about yourself and the company.

I’m a gastroenterologist. I was at Yale on my first faculty job when I was recruited to join UpToDate as a startup. I joined the company, and along with many other capable people, I was able to lead it to grow, scale, and become a very important information resource that is used by healthcare professionals around the world.

Wolters Kluwer acquired UpToDate in 2008. We became part of a portfolio of information services across different verticals. Those verticals include health, tax and accounting, finance and corporate compliance, legal and regulatory, and corporate performance and ESG.

What are the advantages of presenting clinician-authored or clinician-supervised content at the point of care rather than using the literature search engine approach of some of your competitors?

Let’s frame the issue. Patients expect their doctors to give them the best possible advice. It’s a covenant that doctors would be seeking to counsel their patients with the best possible information.

As it turns out, clinicians have regular questions. When they get answers to those questions, they in fact change decisions about 30% of the time. As readers are out there doing the thought experiment of being with their clinician, imagine that they would change their plan if they had a particular piece of information. Those are the stakes.

We decided to address that information need, which has been well documented, by recruiting a faculty of the best people in the world who are clinically active and who are contributing to the body of knowledge in the area that they are writing about.

We framed the approach by understanding the types of questions at an extremely granular level, having an evidentiary way to look at the body of evidence, make that transparent, rate the level as a recommendation so that it’s highly transparent, and infuse into that the wisdom of these people who are some of the most deeply experienced clinicians in the world.

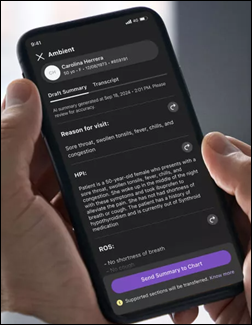

Human curation not only can summarize the body of evidence, but also can add to that the clinical wisdom and experience of considering factors that are important, such as patients’ values and preferences, to issue recommendations that are granular enough to be used at, or near, the point of care.

Doing that purely as a matter of information retrieval, even with advanced technology, is complicated. The expectation is that that technology can ingest all of that material, present it, prioritize it, and consider all of those factors that I just mentioned to make that experience transparent for both clinicians, and ultimately the patients that they’re serving.

Clinical decision support in its early days pushed guidance indiscriminately on physicians, with the assumption that they should digest it all and also to avoid malpractice issues from not offering complete advice. How do AI-focused tools address that, and could AI itself tailor the content to what an individual physician sees and how they react to the information, such as measuring overrides?

That is the frontier and the challenge, and indeed it’s the opportunity. We have plenty of opportunities to inject knowledge at or near the point of care, both for matters that might be more operationally focused, but also in this high-stakes domain of clinical care. Doing that well can improve care, remove friction, and help to ensure that every patient gets the best possible care, no matter who they are seeing and where they are being seen.

Doing that well is extremely challenging. It requires an enormous commitment to be sure that the experience is as accurate and usable as possible. And where feasible, to include information that is relevant to specific patients and make that experience transparent enough so that the clinician who is ultimately making those decisions can feel confident in the accuracy of that decision, or at least to be sure that they can serve as an interpreter when applying it to the patient in front of them.

To do this well, particularly in this area of decision support, requires a enormous commitment. You have to be sure that all of the different components of that which can break down are done as well as they possibly can be, and to provide an experience to clinicians that is as transparent and as effective as possible.

The business model of massively funded OpenEvidence appears to be running drug company ads that are targeted to the retrieved medical information of the patient. Will clinicians see the ad-supported model as a conflict of interest?

We focus on what we do and have always done well. We have been entirely supported through subscriptions. We have extremely strict policies related to conflicts of interest, particularly among our internal staff, but also all of our 7,500 external contributors, the external faculty and peer reviewers who contribute to UpToDate. We have found that important for maintaining integrity, increasing transparency, reducing bias, and ensuring that our sole purpose is to deliver care recommendations that are clear, unbiased, and free of any commercial taint.

Whether that can be done with a different business model remains to be determined. Ultimately, the market will let us know where the cracks are in that type of a model.

We will continue to do what we do and do well, which is to have a commitment to deliver an effective and easy-to-use experience, focusing on making it easy to do the right thing wherever frontline healthcare professionals are working in their EHR in an enterprise environment or on their mobile devices, Making that experience as free from bias as possible to ensure safety to the best of our capabilities. Providing transparency so that the entire experience is grounded in information that has been curated by humans, and in fact some of the most experienced clinicians in the world.

Will standards of care change as enterprise-associated physicians are provided access to sophisticated knowledge tools while others are financially forced to do without or to use free resources such as ChatGPT?

That’s an excellent point. It really comes down to the matter of how widely governance can be established across healthcare enterprises and small institutions as well. Obviously the governance involved in advanced technology such as AI requires a multidisciplinary approach. It’s not clear that that is going to be available widely for all of the different types of institutions that could take advantage of these technologies.

I do think there is a potential for creating a digital divide, or at least to have some institutions which have governance processes in place and others which may be relying on third parties such as their electronic medical record systems to do that governance process for them.

It ultimately comes down to the safety and effectiveness of the information services, particularly in the high-stakes domain of clinical decision support. For an institution that employs doctors, it’s not just the doctors, but it’s the institution itself that has risk involved, along with the potential benefits of helping to achieve high quality, consistent, and safe care. Having the right information available is certainly a fundamental piece of that equation.

Everybody cites the supposed fact that it takes 17 years to incorporate research findings into frontline care. Will that go away as point-of-care tools can put fresh information right on the screen of the person who is making a clinical decision?

It’s interesting you mention that. The 17-year statement has been cited often, to the point where I decided to hunt down one day the original source of that. In fact, there is documentation, but it’s much more nuanced than that. And in fact, it is not 17 years.

A lot of the adoption of new technologies and new approaches is related not just to having the information available, but also other factors, such as financial incentives, convenience, and superiority over alternatives. But there is a process of information diffusion.

UpToDate since its origins has done very well to accelerate that process. We have, for many years, showcased some of the newer concepts in a specific feature within UpToDate called Practice Changing Updates. It describes what is new to ensure that our subscribers have an efficient way to know when practice has changed because of new studies, new guidelines, or simply new knowledge that has accrued.

Now with more tools available at or near the point of care, including Gen AI, that process will continue. Ideally, as new technologies evolve and new knowledge evolves, we as a system will have an easier time at implementing them for the right patients.

The physician who is making decisions from the EHR may be presented with patient summaries or suggestions, information they already know but might miss, and new information that they are seeing for the first time. How do you present that without overloading them data they don’t need?

It’s an excellent point. Doctors are overloaded, and that fact is critical to consider.

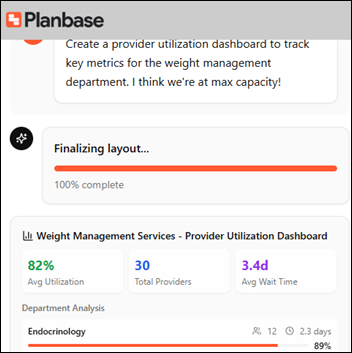

Studies have looked at the number of tasks that clinicians have to perform to fulfill all of the requirements that are expected of them. Primary care, for example, would have to have about 26.7 hours per day to complete all the tasks that are required. That is impossible to achieve, obviously, so there’s always a matter of triage. Designing systems that do not produce a cognitive overload is a critical part of the overall design process, and also the approaches of who should be doing what. It doesn’t always have to be clinician facing.

The potential for overloading clinicians is absolutely there. Many organizations are seeking to have that mindshare and to inject knowledge in front of clinicians, and all of it can’t be done. It has to be prioritized and it has to be effective. How that will look is still a work in progress. There are many efforts to do this using advanced technologies, but there’s also a long track record of what works and what doesn’t work.

I’m optimistic that we can do better and that these advanced technologies will have an important role, but the devil is in the details. How will this work within workflow systems? What will the interaction look like with the data that are available within the clinical record, and perhaps even from other sources, to create an experience that helps frontline providers and their patients? That will be the journey that we’re on.

If I can digress for a moment, what is happening to the patients in all of this? All of what we are talking about is taking place in the background, when there is an enormous erosion of trust in healthcare services and healthcare professionals taking place in the backdrop. Patients are increasingly fed up. They are looking for alternatives. The healthcare system is increasingly unaffordable, and it delivers variable quality of care depending on where you are, your level of insurance, and other factors as well.

In more recent surveys this year, 15% of consumers don’t trust their doctors, which is up from 7% in 2023. Only 24% believe that their healthcare systems are focused on caring for patients, down from 77% in 2020. Instead, about three-quarters believe their hospitals are mostly focused on making money.

This process of busyness and the business of medicine is having a fundamental effect, not only on clinician burnout and the actual care delivery, but in a very fundamental way around trust and the experience that patients are having. Ideally, technology will help this problem, both for frontline providers and for patients who are seeking to have a better, more affordable experience.

We are in that potentially awkward phase where some physicians aren’t interested in technology for technology’s sake, but digital natives are coming out of medical school who can’t wait to do everything electronically. How will that change the way that physicians are educated and then trained?

There has already been an organic adoption of technologies, particularly by younger clinicians and those who are trainees. That has been going on for a very long time. It’s really no different that an adoption cycle occurring with Gen AI as well. Although it’s not uniform, clinicians of all ages and career statuses are facile at adopting technologies for it.

But I do think it will change education in many ways and we’re on that journey as well. One is where AI fits into traditional education and the awarding of continuing medical education credits. Is an AI experience and AI-generated content sufficient and trustworthy, for example, to award continuing education or CME credits?

For students, can you adapt these technologies to support a more effective learning journey and a lifelong learning journey? Certainly AI has been applied for adaptive learning. We at Wolters Kluwer have had a lot of experience in this area, and there are opportunities there.

There’s also training around healthcare professionals being an effective consumer of information services. And particularly now, to understand the limitations of Gen AI and how its convincing and compelling answers can make us falsely believe that they are accurate when they clearly need more interrogation.

A final point is that there is an emerging literature about the degradation of learning from overreliance on Gen AI tools. There is some empirical data that reliance on Gen AI tools might lead to a decreased ability to retain and then to apply that knowledge in other settings. That’s a fundamental pedagogical change. Where this comes out and how educators will approach all this remains to be determined.

For the moment, clinicians at all levels, including trainees, are adopting Gen AI tools. It’s important that the tools that they are adopting to lead to their training and to patient care will be effective, safe, and reliable over an extended period of time.

What about AI governance?

Governance is important. It is tempting to use tools that are expedient. In fact, they are so compelling that there’s a tradeoff that I think clinicians are willing to take around expediency when they haven’t really taken a sharp look at what’s being traded off for accuracy, reliability, and some of the other dimensions of challenges related to the core technology.

The word that I’d like to get out is the emphasis on adequate governance. That can be by a third party, such as the electronic medical record vendor who is forwarding and embedding these tools, or the governance committees themselves at institutions. They need to be sure that all the tools that they are onboarding that are provider-facing, or that take advantage of advanced technologies, are properly vetted, scrutinized against important benchmarks, and transparent. If there are deficiencies, you have the tools necessary to understand those deficiencies over time in domains like we operate such as decision support, where a right and wrong answer to an untrained eye or even to a trained eye can look equally good.

You need a gold standard to be sure that each answer is complete, accurate, and contemporary. That’s hard to do, but nonetheless, that’s the work that needs to be done to be sure that we’re helping all the healthcare professionals live up to their covenant and deliver the best possible care for their patients.

How do you choose a company strategy when AI and other technologies change literally every day?

Across Wolters Kluwer, we have a lot of experience with adopting advanced technologies. Across our verticals, we have already released more than 20 Gen AI related products and services. We are reinvesting constantly into advanced technologies and innovation, including AI, SaaS, blockchain, and other emerging technologies.

In the area of clinical decision support, such as what UpToDate provides, we have to really live up to our own standards in this high-stakes domain. There’s an evolving regulatory framework, but we understand our North Star. We understand in constructing this content that we are part of a medical community. We adhere to those standards. We have 55 physicians who work for UpToDate as deputy editors. Many of them are still in practice, mainly in academic medical centers. So the culture is one of patient safety, of seriousness, of understanding that there is a live patient somewhere behind all of our computer screens.

We have taken our time, as we have looked at the advances and particularly in Gen AI and how they can be applied, so that we adhere to our own standards and the standards that have been expected for our more than 3 million users out there. That means very, very careful product development and extensive testing. We’ve had a lot of innovation around ways to ensure reliability, accuracy, and validity, including not having the known pitfalls of Gen AI solutions like the degradation of context.

These things are very important. Generic Gen AI tools, for example, may recommend drugs that can be unsafe because they don’t ask contextual questions such as, is the patient pregnant? We have found examples of generic Gen AI tools that recommend drugs that are potentially perfectly suitable for the condition, but not if the patient is pregnant or they could be harmful to the fetus.

There have been many examples like that, so we have to understand the limitations of the technology and understand where the technology is going. We grounded it in this database that we have built over 30 years, which is not only summarizing the evidence, but infusing it with the clinical wisdom of deep experts drawn from a faculty around the world.

It’s our own commitment, our own standards, that are deferential to what is expected of us from our customers and the responsibility to take our time to test, release slowly, develop feedback mechanisms, and ground exclusively in UpToDate not the chaos of the internet, and in my view, create one of the most effective Gen AI solutions for decision support that currently exists.

I find it incredibly ironic and rather hypocritical that the co-founder of an Epic-centric consulting firm is calling for the…