Thomas Charlton is chairman and CEO of Goliath Technologies.

Tell me about yourself and the company.

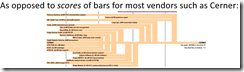

We offer software that plays a critical role in ensuring that clinicians have seamless access to clinical applications so that they can focus on delivering a high quality of care. As a company, our mission is to work with health IT and focus on the areas of availability, speed, and reliability of EHR systems, most commonly Epic, the Oracle Health EHR that was formerly Cerner Millennium, and Meditech.

How would you contrast the use of end user experience monitoring and troubleshooting systems to the traditional model of waiting for users to open trouble tickets?

Users will assign blame when it comes to speed and reliability to whatever they see on the screen. If it’s the EHR, they will say Oracle Health is slow, or Epic is slow, or Meditech is slow. That reflects on the IT organization.

What we’ve found in health IT, which is unique relative to enterprise, is that clinicians are very busy. It’s the unreported issues that are the real problem. Clinicians can take their caseloads to other hospitals where they have privileges. There’s a significant amount of data around burnout.

Through our partnerships with Oracle Health, Meditech, and Epic, we give health IT executives, staff members, and clinical executives the ability to understand if clinicians are having experience issues or usability issues. Who is having those issues? How often do they occur and how long do they last? What is the cause? That is incredibly important, because if you are dealing in the realm of unreported issues, there’s a baseline of consistent dissatisfaction. We provide empirical data so that you don’t have to rely on feedback from clinicians or other users of the technology.

What changes in the first several months after a health system implements your system?

Our technology’s ease of use and price profile gives us the ability to scale to some of the largest health systems. Some of our current clients are CommonSpirit, Ascension, Oracle Health themselves, and small regional health systems such as Southwest General and Maine Health. If you talk to of those, they will say that it’s being able to quickly identify issues that affect clinicians. We do it with data. It’s easier to identify and fix problems when the root cause is identified.

They will also say that the clinician experience is substantially improved, because we’re not just solving reported issues more quickly, but providing visibility into unreported issues. They would cite a reduction in reported issues, a substantial reduction in the mean time to remediation, and immediate assessment of the criticality of issues.

Imagine that you are receiving a large number of complaints from the 10,000 users in your health system. That makes it seem as though there are problems everywhere. On demand, you can run a quick report through our technology so that you can frame up where the problems are occurring, who is having those issues, and very likely identify the root cause.

Probably one more thing to note is the vastly improved communication between health IT and the clinical sides of the health system. Conducting surveys is the traditional method that is used to gauge clinician and user satisfaction with EHR applications. But surveys are not timely. They don’t provide actionable data. They are subjective. We bring empirical data into that subjective conversation. Both sides of the organization, clinical and IT, are looking at a common set of facts and figures around end user experience.

How are user experience problems spread over application problems, infrastructure, connectivity, and third-party software?

If you look at KLAS’s House of Success, a number of factors support a good EHR experience for a clinician or user. One of the factors is application processes. How many clicks does it take to admit a patient or download a lab report? We don’t deal with that. We focus on availability, speed, and reliability.

In that situation with those three components, it is a complex mesh of technologies. If you think of just the simple logon sequence, are they using Citrix or VMware Horizon to grant secure access to these applications? Are they hosted, primarily like Oracle Health, or on-premise like Epic and Meditech, although that’s changing because they both have cloud offerings now.

You have the user. You have whatever their particular device is. You have where they’re connecting from, the service provider, the network, and then back into the back-end systems that support the application. We cover all of those variables.

We’ve had years of experience and many man-years of development to be able to automatically correlate data from various sources, look at the end user experience specifically, and determine that of all of those factors, which are the most likely root cause of the issue. We use a combination of AI-enhanced data, automation, and embedded intelligence to be able to determine which of those. They are all silos in an IT organization – database, application, end-user device, server, et cetera. We use data to determine which of those silos, one or more, is the root cause of the various issues.

What is the cultural change of an organization that moves from a complaint-based system of clinician satisfaction to a fact-based, measurable data approach?

It’s phenomenal. If you can’t frame up the problem, if you don’t know who is having problems, the frequency of those problems, the duration of those problems, and why they occur, it is literally impossible to take any action.

Clinical executives would hear complaints from their clinicians. Health IT wants to provide a good clinician experience for all the reasons that we’ve talked about, including the impact on patient care. But if you don’t have data, how do you determine where the root cause is? You can’t frame up whether there is a critical issue or not.

We find from the health systems that use our technology that communication between the clinical side of the house and IT is vastly improved. You have engineers on one side and scientist clinicians on the other side, and now they are able to look at data. Data is friendly. It may not be welcome data, but it is objective. We are bringing actionable data into what is typically a subjective dialogue. They can look at our data as a team and put together a productive plan to resolve issues permanently.

How is the experience of clinicians affected by off-campus locations, remote work, and the use of mobile devices?

We have a great example from the University of Kansas Health System. A clinician is working in the hospital. They have great system performance during the day. They go home at 6:00 or 7:00 at night and their performance using Epic is fine. Around 11:00, a call comes in. The clinician is in their bedroom, they need to access Epic, and now the performance is slow. The performance should not be slower because there are fewer people using the systems at that time of night, yet there is the reality of that.

The IT folks can run a report in our product and show the varying degrees of connectivity that happen. They can sit with the physician and say, if you look at your entire day over the last 30 days, the problems that you are having are always at this time at night. Where are you at those times? They were able to determine, oddly enough, that it was because there was a lack of connectivity on the other side of the physician’s house. They were too far away from their router in their home.

This is what changes the paradigm. We are able to deliver both to health IT as well as to clinical executives on demand that visibility into the clinician’s experience with their EHR application as it relates to availability, speed, and reliability. You no longer have to be in a reactive mode. You can be proactive and understand where issues might be occurring so that they can be preemptively solved. It really changes the dynamic and improves the satisfaction of the clinicians. It’s not uncommon for health IT executives to say that we’ve helped improve the reputation of IT.

What opportunities are you seeing to be able to use AI to enhance your products?

We’ve had AI in our product now for about eight months, so this is Version 1. AI makes fault isolation and resolution easier. It reduces the mean time to resolution.

It also democratizes deep IT knowledge. A ticket or complaint comes in, it goes to a help desk, and then it’s escalated. When it’s escalated to Level 2 or Level 3, these are very serious issues. They are causing clinician experience issues, and very likely have patient impact. Those very experienced IT technicians have to spend a tremendous amount of time without our technology trying to understand where the root cause is.

We use a combination of AI-enhanced data to show them where the issue is. We also offer suggestions about how to resolve the issue.That has given our organizations the ability to push the resolution of those issues down to lower levels.

You may have a clinician who is interfacing with a patient and is having speed and reliability issues. Every one of those help desk escalation points is a delay to reaching a solution. Our technology allows resolving issues at Level 1 support, as opposed to being escalated to Level 3, where it’s put in a the working queue of an experienced IT engineer and can take quite a bit of time to resolve the issue. By pushing resolution down to lower levels, we are able to reduce the mean time to resolution, which impacts clinician satisfaction and ultimately delivers a higher quality of patient care. It allows the clinician to focus on patient care and not technology enablement.

What are the key parts of the company’s healthcare strategy over the next few years?

We’re going to add more and more enhancements that give our health IT organizations the ability to resolve issues more quickly and be able to prove the root cause so that permanent fix actions can be put in place. Reducing the mean time to remediation and providing empirical data so that the quality of the clinician experience with Cerner, Epic, or Meditech can be improved demonstrably over time.

When looking at clinician EHR satisfaction. speed and reliability are the easiest things to change. They have the highest impact on clinician frustration. It’s easier to identify where these issues are. The fixes are quicker than training, education, and application changes. They impact physicians greatly, because when they are experiencing speed and reliability issues when they are in a environment with a patient, it’s visible to the patient and therefore the most frustrating to them personally.

Comments Off on HIStalk Interviews Thomas Charlton, CEO, Goliath Technologies

"The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) posts an anticipated future contracting opportunity for a correctional EHR for ICE detainees,…