Top News

HIMSS reschedules its HIMSS21 conference to August 9-13 in Las Vegas. It was originally planned for March 1-5.

HIMSS22 reportedly remains on schedule in Orlando for March 2022, just seven months later.

Reader Comments

From Pearl Drops: “Re: HIMSS21. In August? In Las Vegas? Really?” My reaction:

- Assuming the event actually happens a year from now, it will have been 30 months since the last live HIMSS conference. Relevance is a crapshoot given the ill will created by the HIMSS20 refund policies, the pandemic’s financial impact on exhibitors and attendees, and the many months everybody will have had to decide whether they should just show up lemming-like as usual or instead look harder at ROI. People have learned to live without restaurants, sports, and concerts in their absence with potentially permanent impact, so a full-fledged return to conference life is far from assured.

- The email says HIMSS22 will remain on track for March in Orlando, which would mean doing it all over again just seven months later, so the fatigue factor could be significant.

- The revenue hit to HIMSS is surely monumental just from timing alone, not even considering a likely big drop-off in exhibitor and registrant revenue.

- The timing of HIMSS20 could not have been worse for HIMSS since it coincided with the early start of a long pandemic, thus impacting at minimum both HIMSS20 and HIMSS21. RSNA20 moved to a virtual event in losing one live conference, but its 2021 conference will take place as planned unless 2021 is a full-year scratch, in which case HIMSS will be in even more trouble.

- I visited my least-favorite city of Las Vegas in late June a few years back to scout HIStalkapalooza venues, and it was nuclear hot even then. I swear my flip-flops started melting while walking to the pool, which was steamier than any hot tub should be. Miserable outdoor heat is good for exhibitors and casinos, however.

From Concision: “Re: health IT articles. Have you noticed how long they take to get to the point and start off reciting the obvious?” I have. Writers are either short on skill or long on vanity when they can’t lead off with compelling information and instead meander around before making some questionably valuable point. I turned down a lot of Readers Write articles because of my #2 test (after #1, “don’t pitch your company”) – if three randomly chosen sentences don’t contain anything insightful or fresh, or if the opening sentences stiffly recap universally known facts, then you’re wasting the time of readers.

From Vaporware?: “Re: DoD. Fascinating update from Cerner earnings call, and a reminder that the CommonWell Vaporware Alliance was formed in March 2013 to address the DoD’s expressed desire for an interoperable EHR.” Cerner mentioned in the earnings call that DoD and the VA launched a joint HIE in April and will connect to CommonWell later this year.

HIStalk Announcements and Requests

Welcome to new HIStalk Platinum Sponsor Everbridge. The Burlington, MA-based company is the global leader for integrated critical event management (CEM) solutions that automate and accelerate organizations’ operational response to critical events to help keep people safe and businesses running faster. More than 1,200 hospitals rely on the Everbridge CEM Platform to deliver resilience on an unprecedented scale. With COVID-19, Everbridge is helping hospitals to safely resume care and establish a new normal with a robust risk mitigation and emergency response platform that offers automated contact tracing and wellness checks, safe and secure telehealth, critical events management platform, incident management response for cybersecurity risks, and digital wayfinding with blue-dot turn-by-turn navigation. Thanks to Everbridge for supporting HIStalk.

Webinars

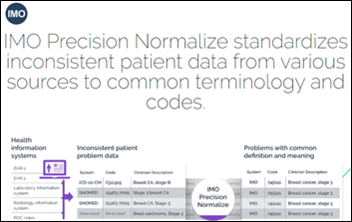

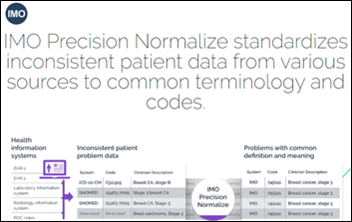

August 19 (Wednesday) 1:00 ET. “A New Approach to Normalizing Data.” Sponsor: Intelligent Medical Objects. Presenters: Rajiv Haravu, senior product manager, IMO; Denise Stoermer, product manager, IMO. Healthcare organizations manage an ever-increasing abundance of information from multiple systems, but problems with quality, accuracy, and completeness can make analysis unreliable for quality improvement and population health initiatives. The presenters will describe how IMO Precision Normalize improves clinical, quality, and financial decision-making by standardizing inconsistent diagnosis, procedure, medication, and lab data from diverse systems into common, clinically validated terminology.

Previous webinars are on our YouTube channel. Contact Lorre to present your own.

Acquisitions, Funding, Business, and Stock

Allscripts reports Q2 results: revenue down 8.6%, adjusted EPS $0.18 versus $0.17, beating Wall Street expectations for both.

Allscripts will sell its EPSi business unit to Roper Technologies-owned Strata Decision Technology for $365 million.

Cerner reports Q2 results: revenue down 7%, EPS $0.44 versus $0.39, beating consensus earnings expectations but falling short on revenue. From the earnings call:

- The company says its revenue came in lower than expected because the pandemic impacted sales or timing of some low-margin offerings, such as technology resale and billed travel.

- Q3 revenue expectations have been reduced because of divested businesses and a larger-than-expected pandemic impact, but the company expects earnings to grow due to cost reduction.

- The company says it won’t cut R&D spending.

- Cerner says that while virtual go-lives work for simple implementations, the future model will be a hybrid, with fewer people on site who are supported centrally, which also reduces billable travel for the client. The company notes that employees are 25% more productive working remotely because avoiding two half-days of travel during the work week means they have five days billable per week instead of four.

- Cerner is looking beyond its Amwell virtual visit partnership to virtual hospitals and ICUs that would involve its CareAware platform.

- An analyst asked about a $35 million acquisition that he saw on the cash flow statement, which Cerner says was for a cybersecurity company that it can’t talk about otherwise.

- Cerner is interested in acquisitions related to research data and analytics.

- The grating phrase “new operating model” thankfully wasn’t uttered even once.

Teladoc Health reports Q2 results: revenue up 80%, EPS -$0.34 versus –$0.41, beating revenue expectations but falling short on earnings. Expenses increased 63%, mostly in marketing, sales, technology, and acquisition costs, and the company projects a loss per share of $1.36 and $1.45 for the year.

Private equity firms TA Associates and Francisco Partners invest in healthcare clearinghouse operator Edifecs at a valuation of up to $1.8 billion.

Private equity firm Leonard Green & Partners acquires a stake in WellSky from TPG Capital that values the company at over $3 billion.

Ciox Health acquires NLP vendor Medal to enhance its real-world data business for drug companies and researchers with information extracted from unstructured EHR data.

NantHealth acquires OpenNMS, which offers an open source network management system.

In-hospital specialty care telemedicine provider SOC Telemed merges with Healthcare Merger Corp. in a complicated transaction that will create a Nasdaq-listed company that values SOC at $720 million.

Sales

- Australian Capital Territory government chooses Epic for implementation across Canberra’s public hospitals and community health centers in a 10-year, $80 million contract.

- Summit Healthcare announces several new clients for its Summit All Access for web-based and mobile information sharing, including ADT notification, community data sharing, and downtime data access.

- Franciscan Health chooses Accruent’s Connectiv software, based on ServiceNow, to manage its facilities and biomedical assets and devices.

People

David Tucker. MHA, MBA (Huntzinger Management Group) joins 314e as VP of sales and client services.

Announcements and Implementations

WebPT adds 1,700 clinics to its rehab therapy platform in the first half of 2020 as the company rolled out a virtual visit system, a digital patient intake feature to minimize waiting room contact, and increased use of its patient relationship management solution.

Diameter Health releases its turnkey FHIR Patient Access solution that allows payers to comply with CMS requirements that they give members access to their data using FHIR standards.

Goliath Technologies creates a managed service offering for remotely monitoring the availability of applications running under Citrix and VMware Horizon, which allows clients to make sure users aren’t having problems accessing business applications from home or other offsite locations.

InterSystems lists how its TrakCare health information system has been globally deployed in response to COVID-19, including rollout of a screening module that was installed on site in Beijing early in the pandemic, connecting labs and temporary hospitals in Madrid, creating interfaces between new COVID-19 testing machines to its lab system in 48 hours, and implementing TrakCare Lab Enterprise for the 118 COVID-19 labs of the UAE’s Pure Health in two weeks.

Premier enhances its crisis forecasting and planning technology to predict a given hospital’s COVID-19 patient census in near real time.

DirectTrust releases the draft of its Trusted Instant Messaging+ standard for testing.

Aiva offers customers of its in-room patient communication system – which is powered by voice assistants such as Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant — with caregiver-to-caregiver technology from Hillrom’s Voalte.

Cerner will add Nuance’s virtual assistant technology to Millennium, allowing users to navigate by voice for chart search, order entry, and scheduling.

Intelligent Medical Objects launches IMO Precision Normalize, which standardizes diagnosis, procedure, medication, and lab data from diverse systems into common, clinically validated terminology.

Government and Politics

An NPR investigation into HHS’s awarding of a $10 million contract to health IT vendor TeleTracking for a COVID-19 hospitalization data collection system finds several irregularities:

- HHS first said the contract was sole source, but now says it was competitively bid among six companies that it declines to name using criteria that it declines to list.

- The process HHS used to award the bid is normally used for innovative research, not the development of government databases.

- TeleTracking’s CEO is a long-time Republican donor who is loosely connected to a company that financed billions of dollars worth of Trump Organization projects.

- The contract ends in September and TeleTracking says it hopes for an extension, which could cost millions. The current contract is 20 times larger than all of TeleTracking’s previous federal contracts combined.

COVID-19

The US now leads the world in number of COVID-19 deaths per day, averaging over 1,000 and most recently hitting nearly 1,500 as total US deaths crossed the 150,000 mark. The US has less than 5% of the world’s population, but nearly 25% of its COVID-19 deaths.

An HIStalk reader reports that their large Texas hospital has been forced yet again to change COVID-19 testing platforms due to a nationwide supply shortage, leaving clinicians and the IT folks scrambling. Delayed results force clinicians to assume that the patient is positive, which requires them to needlessly use PPE that is also in short supply.

The COVID Tracking Project says COVID-19 hospitalization data is now unreliable, partially due to HHS’s no-notice switch to a new reporting system:

- Some states can’t report their data at all, some hospitals have stopped submitting data, and hospitalizations don’t always line up with local case counts.

- HHS and state-reported hospitalization information is sometimes dramatically different, with HHS oddly reporting higher numbers much of the time.

- HHS collects information of all COVID-19 hospitalizations, including suspected cases, but some states report only those cases in which COVID-19 is the primary diagnosis.

- States that collect information from state hospital associations may not be reporting numbers from the VA or other federal hospitals.

- Each state decides on its own which information to make public on dashboards and reports, which then feeds national dashboards such as that of the COVID Tracking Project.

- Case, testing, and death data remain accurate because the information was not affected by HHS’s change.

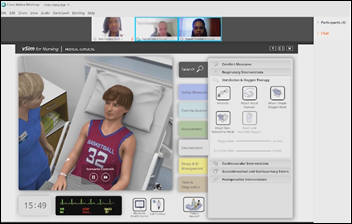

University of Colorado School of Medicine describes in a JAMIA article how it applied informatics interventions to meet UCHealth’s COVID-19 challenges, drawing on the relationships its doctors and nurses have with frontline staff and their experience in leading change. The team:

- Used an electronic teaching tool to ramp up EHR training for nurses who were being prepared for inpatient roles.

- Developed an electronic training guide for volunteer clinicians that included embedded videos and linked resources that covered, EHR, rounding, and common patient conditions.

- Created new Epic-based pathways using AgileMD that included proning, clinical trials, convalescent plasma, antivirals, anticoagulation, intubation checklist, septic shock, and hyperinflammatory response treatment.

- Added “indication for use” to discourage unapproved use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin.

- Created a Virtual Health Command Center to train clinicians on its Epic-integrated Vidyo virtual visit system in two weeks.

- Coordinated with the patient experience team to present training webinars on conducting video visits, including non-verbal communication and reflective listening.

- Partnered with Masimo to deploy a wearable device for discharged patients to monitor respiratory rate, heart rate, and pulse oximetry.

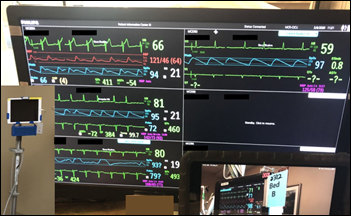

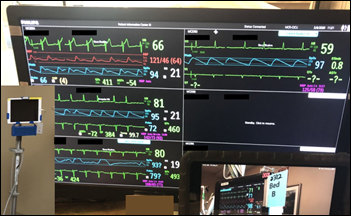

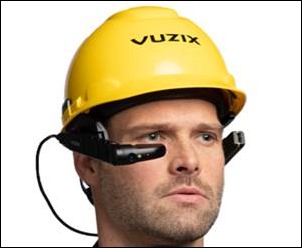

- Redeployed tablets to COVID-19 units to minimize staff exposure, to provide remote translator service, to help the palliative care team convene videoconferences with patients and families, to present group therapy for psychology and rehab, and to capture audio and video from non-networked monitors so that nurses can listen for alarms from the nursing station (pictured above).

- Created a Microsoft Teams collaboration site for regional intensivists, which then led to creating a public website for community providers.

- Developed logic for three levels of COVID-19 chart alerts based on patient check-in information.

- Developed note templates to store patient advance directive status in a central location.

- Helped nurses who were not able to work in the hospitals to use Epic Secure Chat to follow patients and then update their families, who were not allowed to visit.

- Created a scoring tool to ration therapy if needed.

- Studied EHR data for information that could be predictive of hospitalization rates.

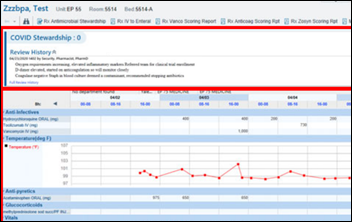

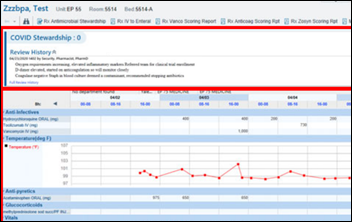

Yale New Haven Hospital describes how it customized Epic’s antimicrobial stewardship module for COVID-19, developing patient lists, assessment tools, and a handoff process, all to support reviewing a large number of patients quickly and to optimize their management.

Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD raises an interesting economic point.

Wolters Kluwer Health uses clinical search activity in its UpToDate reference, along with online and mobility data, to predict COVID-19 outbreaks in specific areas.

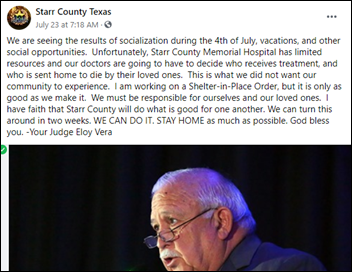

Seventeen University of Florida Health anesthesiology residents and one fellow contract COVID-19 after attending a party that was attended by 20-30 residents. The health system refused to acknowledge either the outbreak or the party in inappropriately citing HIPAA.

Former Republican candidate for President Herman Cain dies at 74 of COVID-19, for which he tested positive nine days after attending President Trump’s June 20 Tulsa rally without wearing a mask even though he was a Stage 4 colon cancer survivor.

The House of Representatives requires members to wear masks following the COVID-19 diagnosis of Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-TX), who previously refused to wear a mask for protection against the “Wuhan virus” and then speculated after testing positive that, “I can’t help but think that if I hadn’t been wearing a mask so much in the last 10 days or so, I really wonder if I would’ve gotten it.”

Amazon Prime Air drone engineers design NIH-approved face shields that Amazon will sell at cost to frontline workers, saving them at least one-third over other reusable face shields at $2.65 each. The company is also offering an open sourced design package for 3D printing and injection molding.

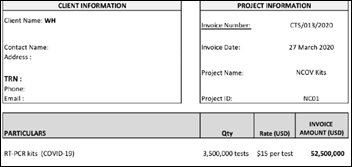

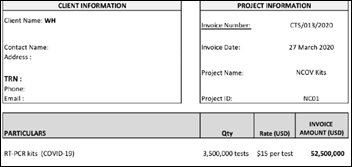

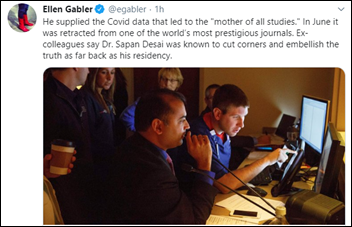

A Vanity Fair investigative report finds that a White House panel led by Jared Kushner developed a national COVID-19 testing strategy and ordered 3.5 million China-produced tests for $52 million from a company connected to the ruling family of the United Arab Emirates, but the tests were contaminated and unusable. The group’s national testing strategy was never announced and testing responsibility was eventually moved to individual states, to the group’s surprise. It called for federal distribution of test kits, oversight of contact tracing, lifting contract restrictions on where doctors and hospitals send tests so that any laboratory could perform testing, reporting all test results to a national repository as well as state and local health departments, and rapidly scaling up antibody testing to support returning employees to work. It also proposed establishing a “national Sentinel Surveillance System” with real-time identification of hot spots. The plan lost favor with President Trump, who insiders say was worried that more widespread testing would increase case counts that would harm his re-election chances. He favored optimistic coronoavirus models from Deborah Birx, MD that were eventually proven to be wildly wrong. The report also found that one member of Kushner’s team argued that a national plan would squander the political opportunity to blame Democratic governors of states that were being hit hardest early in the pandemic.

Other

Nacogdoches Memorial Hospital (TX) and Cerner agree on partial payment to settle the $20 million the hospital owes for an implementation it delayed repeatedly and finally cancelled.

Sponsor Updates

- Diameter Health launches FHIR Patient Access to help payers comply with federal regulatory requirements to provide members with access to their health data using FHIR standards.

- TriNetX will conduct a medical record review of 200 hospitalized COVID-19 patients to create a dataset that can be used to support drug treatment and vaccine research.

- InterSystems introduces a new credentialing program for its products and technologies.

- Fortune profiles the way in which Jvion re-focused its CORE technology to develop a COVID-19 community vulnerability map.

Blog Posts

Contacts

Mr. H, Lorre, Jenn, Dr. Jayne.

Get HIStalk updates.

Send news or rumors.

Contact us.

Look, I want to support the author's message, but something is holding me back. Mr. Devarakonda hasn't said anything that…