EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 10/3/19

Fall is finally here in my part of the world, although areas of the US are still near broiling. October 3 marks the start of the last 90-day EHR reporting period for those of you playing the Promoting Interoperability home game, hospital edition. Those not reporting for a continuous 90 days in the calendar year will receive a downward payment adjustment. Hospitals must also respond in the affirmative for the Prevention of Information Blocking and ONC Direct Review Attestations.

Speaking of reporting, I somehow wound up on an email list for Greenway Health customers. Apparently, there is an issue with the Greenway Patient Portal and settings that allow providers to block sending laboratory data through the portal. Originally designed to keep sensitive information from being sent, if the setting is enabled then the entire site is unable to attest to certain MIPS and Medicaid measures. Providers were advised to adjust their settings prior to October 1 so that they would have data for the 90-day collection period ending December 31. Seems like something that should have been found earlier in the year, and I’m still puzzled how I wound up on their mailing list.

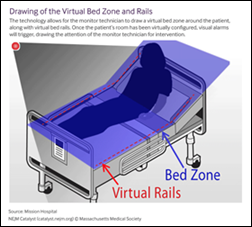

For anyone who has worked with hospitalized patients, we know how challenging it can be when patients are disoriented or at risk for falls. I was excited to read this case study about virtual sitters in the hospital environment. Mission Hospital in Asheville, NC piloted virtual sitters in its neuroscience unit. They noted a 23% reduction in falls and a 12% reduction in fall-related injuries during the 12-month pilot. Mission Health worked with Cerner to develop the virtual sitter system, using Microsoft Kinect technology to monitor patient movement. The solution included two-way audio, voice recognition, and customizable alerts. Technicians could monitor six patients at a time, and if patient movement occurred, the technician would be alerted to the specific feed. Similar to when an in-person sitter is used, the technician could use voice instructions to try to redirect the patient if needed. If the intervention isn’t successful, the technician can alert nursing staff to intervene in person. Large hospitals can spend millions of dollars on sitters, so this technology has the ability to significantly impact the bottom line.

Despite what the folks at Apple may have us believe, the iPhone isn’t the be-all, end-all of smart phones. I always cringe when a vendor launches a solution that is only available for the iPhone, as if those of us who use Android are some kind of second-class citizens despite Android having a slim majority of market share. I ran across a press release about a non-profit industry group that is working to create an open-source version of the Apple Health tool kit that can be used by Android users. Members of the CommonHealth project team include Cornell Tech, UC San Francisco, Sage Bionetworks, Open mHealth, and The Commons Project. The plans include robust governance to review partners and apps requesting to connect through the platform. UCSF is piloting along with other academic medical centers and health systems. I’d be interested to hear from anyone who is involved in the project.

From Incognito: “Dr. J – You are on to something when you note that switching back and forth between scribes and flying solo is a bit of a thing. I am convinced that EMRs bring a very different and intense kind of cognitive load than the analog world did, even without accounting for all the ‘little things’ that have been added to the physician’s thought process (because now, ‘they’ can). Adding a scribe is really just another piece of that cognitive load, even if it does reduce some bits. Switching back and forth flies in the face of ‘standard work’ in good processes. I’m sure that there are industrial design and psychology/perception experts who can tell us what we are doing to ourselves. They see it in fighter pilots and in air traffic controllers – and in Facebook ads.” Fortunately, I had a scribe all day today so things ran smoothly. Unfortunately, it’s probably the last time I’ll work with him since he’s getting ready to travel to residency interviews. Today’s scribe is a fully qualified physician, trained and licensed in another country. He’s been a delight to work with, even though his employment is a direct result of our broken health system that doesn’t always allow international medical graduates to perform the functions they might otherwise be able to. He plans to complete a residency in internal medicine so he can practice in the US, since he’s a dual national also holding US citizenship.

There was an article in my local paper about the explosive growth of urgent care facilities in the US, and not surprisingly several local physicians wrote scathing editorial letters claiming that urgent care providers are guilty of rampant overprescribing of antibiotics. The same claims are often made of telehealth providers, even though some have better data on others on how well they avoid unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. It can be difficult to get data out of EHRs to run those types of reports, and even more difficult to try to use technology to limit prescribing, as one reader recently wrote:

“At my facility, we get fairly regular reports on antibiotic stewardship. Oddly enough the EHR is one of the roadblocks for doing what we want and need to do in this area. Tracking antibiotic use requires substantial pharmacist and infectious disease physician time where a well-designed EHR should have easy-to-use canned modules for tracking use as compared to the latest local microbiology profile. More importantly, there is no straightforward/easy way to restrict specific drugs to be ordered only by certain specialists, on certain floors or services, or with co-signatories or approvals by another service. Oddly enough, it seemed easier to implement such restrictions in the pre-EHR era. One issue is that we don’t want to block all direct prescribing of specific antibiotics since we are very mindful of not restricting initiation of a potentially life-saving antibiotic in an emergency situation such as impending sepsis. The issue of drug-specific prescribing restrictions is not just a problem with antibiotics – we have the same issues in trying to restrict rampant prescribing of other costly drugs.”

There’s no perfect system out there that can prevent all imperfect human behavior from happening. I know providers who consistently do sketchy things regardless of the education they receive, and probably the only thing that would block those folks would either be a hard stop in the EHR or a disciplinary action. Even though the organizations I’ve worked for take a dim view of such behaviors, there’s a delicate balance between admitting volumes, revenue generation, and tolerance for those who know where their bread is buttered.

Has your organization figured out how to effectively transform physician prescribing behaviors? Was it high-tech or high-touch? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

I've figured it out. At first I was confused but now all is clear. You see, we ARE running the…