EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 9/9/21

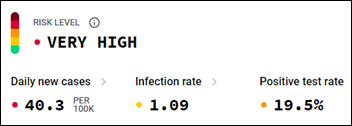

Lots of chatter in the healthcare community about the percentage of workers having “breakthrough” infections despite being fully vaccinated. Various investigations are looking at causes, including waning immunity, the increased transmissibility of the delta variant, and more.

It still boggles the mind that a year and a half in, we have not come to consensus on the fact that all healthcare workers need to be wearing high-level personal protective equipment. None of the hospitals in my area are providing adequate N95 respirators for their healthcare workers, the vast majority of whom are expected to see all patients wearing a surgical mask. The reality in our community is that a good number of people walking into healthcare facilities are indeed COVID-19 positive, so those on the front lines really need better protection. I was in an outpatient office today and staffers were wearing cloth masks and not even surgical masks – it is hard to believe that anyone thinks that’s appropriate in a healthcare setting. At times, it seems like embracing the new normal is instead a race to the bottom.

I booked my HIMSS22 hotel reservations today, despite the HIMSS website being completely confused as to what year we’re talking about. The HIMSS rate for my hotel of choice was $60 per night less than the rate on the hotel’s website, and with the post-COVID-19, less-draconian HIMSS cancellation policy, booking it through OnPeak was a no-brainer. The only reason I thought about booking my hotel was the fact that I received an email asking for HIMSS22 proposals.

I’m glad I got in at a reasonable room rate, although I wish there were more hotels closer to the convention center. I don’t mind getting my cardio in on the way to the conference, but my feet are definitely tired at the end of the day. Back to the call for proposals – they are due by September 20 and can be submitted for general education Sessions, preconference symposia, and preconference forums. Interested applicants can visit the HIMSS website, but don’t be thrown off by the ongoing presence of the HIMSS21 logo.

For those of you responsible for maintenance of the back end of EHR, practice management, and revenue cycle systems, the American Medical Association this week released its Current Procedural Terminology code updates for 2022. There are over 405 changes this time, around including nearly 250 new codes, 60 deletions, and nearly 100 revised codes. There are updates to vaccine codes and additions for remote patient monitoring and care management for patients with chronic conditions. Organizations need to look at the list of changes and determine how it impacts their physicians, coders, and other personnel. It’s not as simple as updating the codes in the tables of the IT systems – often changes are needed to workflows and education for end users is definitely a good idea. The changes take effect January 1, 2022.

Teladoc health announces open nominations for the She Powers Health awards, which are designed to “shine a light on diversity and inclusion initiatives across the healthcare industry that address the disparity of women in executive and board positions.” The third annual awards reception will occur at the HLTH 2021 conference. There are two awards, with the first being the Individual Award, which recognizes someone “who has not only made a significant impact on peoples’ health, but who also has recognized, empowered, and championed women and the important role they plan in enhancing care and transforming the healthcare industry.” The second award is the Rising Star Award, targeted at a member of the under-30 crowd “who has made an impact on peoples’ health, empowers women in the workplace, and is a champion for diversity and change, while still early in their career.” Nominations close September 17, 2021.

Jenn tipped me off on a recent job posting. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has posted for a chief experience officer. The chief experience officer is expected to work with CMS stakeholders to improve customer experience delivery and to develop and implement strategies for CMS to use as part of its routine development process. Additional responsibilities include promoting continuous change and developing a voice of the employee program to promote retention, recruitment, engagement, and productivity. The salary range is commensurate with government employment, so I suspect the position will attract those who are truly motivated to serve as opposed to those who seek C-level titles for other reasons. If you are interested, apply quickly, as Friday is the closing date for applicants to submit their materials.

Speaking of job postings, I’m working with a client right now who picked the wrong team for a project and now is trying to clean up the mess. It’s a case study in the need to really understand the skill sets you need for your team to be successful and to make sure that everyone has the minimum skills needed to move the project forward. Just because a physician is “interested in technology” doesn’t necessarily mean they’re suited for a role on a technical team. You can be the most brilliant clinician in the world, but if you can’t figure out how to work with Confluence and Jira, it’s going to be difficult to keep up on an agile team.

Despite training, they are struggling, and I’m almost to the point of recommending that we hire the equivalent of a scribe to assist them with their daily tasks. Paying for an intern or assistant would be cheaper than burning hours at a physician rate, for sure. On the other hand, they mastered biochemistry and passed their board exams, so I’m cautiously optimistic.

One of my other projects this week has been shopping for a new phone. My trusty Motorola is being rendered obsolete by upgrades to my carrier’s network, so despite the fact that it meets all my needs and doesn’t give me any trouble, I have to retire it. Several of my friends are trying to get me to cross over to the land of the iPhone, but I’ve been happy with Android ever since giving up my beloved Blackberry, so I think I’ll stay put on platform. I’ve heard the changeover to the phone I selected is easy and straightforward, so wish me luck as I’ll be working through it this weekend.

What’s the best or worst thing about upgrading your phone? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

The story from Jimmy reminds me of this tweet: https://x.com/ChrisJBakke/status/1935687863980716338?lang=en