EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 1/2/20

Regardless of what holidays you celebrate, everyone is impacted by medical offices that are closed and healthcare facilities that are running on modified schedules this time of year.

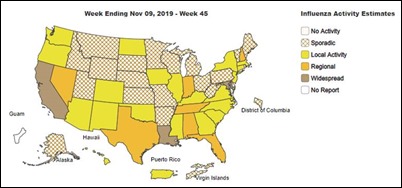

I’m in the middle of a streak of clinical shifts that have at times reduced me to a mound of quivering jelly. Influenza is definitely on the rise and I’m starting to feel like my mask is permanently attached to my face. Our urgent care group saw nearly 2,000 patients on December 26, breaking our city-wide record. Many patients reported trying to get in touch with their primary care physician only to find the office closed, with some offices being closed until after the new year.

Seeing a 20% bump in volumes, the IT side of my brain always wonders about scalability of the solutions we use. I’m happy to report that the EHR held up like a champ, but viewing radiology images in the PACS was another story entirely. Load times were running up to two minutes, which seems like an eternity when you’ve got a full house and need to know what’s going on with your patients’ films.

One of my patients happened to be an imaging rep, who asked how we were holding up this time of year. It was nice to see someone who understands that there are many factors behind keeping an office running, although he was less than amused that we couldn’t send his records to his primary physician.

As an independent organization, the large health systems in town aren’t too keen on sharing data with us even though it would mean they receive our work product as well. Just another example of information blocking that isn’t a vendor’s fault. In the meantime, I take full advantage of the features within Epic that allow me to access patients’ charts for a short time with their permission.

My operations brain is always challenged by these high-volume days. They make me wonder what “the system” could do differently to better manage these patients. Although many of those we saw had acute conditions that needed urgent treatment, like influenza or pneumonia or lacerations, many of them could have been handled by a nurse triage line or other lower-acuity situation.

Quite a few patients hadn’t tried any self-care, not so much as a decongestant or an over-the-counter cough medication, even though they were relatively young and healthy and didn’t have any reason to be concerned about medication interactions or worsening of chronic conditions. Several had been sick for less than a day. My favorite presenting issue of the day was, “My throat started with a tickle a couple of hours ago and I just wanted to see what it was.” This shows a lack of health literacy, even in the relatively affluent area in which I was working. What could we as a healthcare system do to serve these patients better?

I’ve also been able to put my telehealth hat on this week, due to a spike in volumes in my state. I only do telehealth visits sporadically since I don’t hold a lot of different state licenses. I was pleasantly surprised by the number of patients who weren’t specifically seeking antibiotics – who just wanted to make sure they were doing everything possible to treat their condition, or wanted validation of their treatment plan because they were making slower than expected improvement.

Back in the clinic the next day, I also saw the dark side of some virtual visit care as patients came in for face-to-face visits after having been prescribed medications that seemed unrelated to their symptoms. I saw three patients from the same physician who were each a bit concerning. It sounds like her practice has recently started using functionality within Epic that allows for patients to have billable asynchronous visits, and perhaps she isn’t in the swing with the fact that just because a visit is virtual doesn’t mean you don’t have to follow the standard of care. Maybe she doesn’t know the antibiotics she is prescribing aren’t indicated for the condition being treated, but there’s no good way to try to address that professionally when we see it.

Our volumes continued throughout the weekend, with record-breaking numbers of visits at several of our locations. I encountered a couple of primary physicians and one psychiatrist whose offices were not only closed during the holiday weekend, but also who had no after-hours coverage. Even other physicians received no response when trying to reach them. In my state, that’s tantamount to patient abandonment, and I hope those patients have some difficult conversations with their physicians (or perhaps soon-to-be-former physicians) about being left hanging.

I also heard some complaints from patients who just don’t feel like their physicians listen to them. It’s not only complaints about looking at the computer instead of the patient, but also complaints about physicians pushing additional procedures that are unrelated to their care plans. One patient showed me the brochure from her pulmonologist who was offering cosmetic Botox injections. These are just a small sample of the patients who wind up in the urgent care, where they’re trying to make up for whatever they’re not receiving in their usual setting of care, if they have one.

Santa must have been very good to a couple of patients, who presented with ICD codes in the F12 series: cannabis-related disorders. Cannabis-induced palpitations was one of the conditions, and I would have loved to have simply typed “lay off the weed” in my care plan. Somehow “reduce or eliminate cannabis use until cleared by cardiology” just doesn’t seem as festive. Nor does “your risk of recurrent vomiting would be lower if you stopped using marijuana.” These are the things they don’t tell you about in medical school, that one day you might find yourself dealing with in an exam room.

On days like these, I long for the relative lack of excitement found in a good lab interface build or some of the other work I do in my informatics practice.

For those of you who worked around the holidays, what kinds of adventures did you have? Any great stories? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Fun framing using Seinfeld. Though in a piece about disrupting healthcare, it’s a little striking that patients, clinicians, and measurable…