EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 12/13/18

CMS announced an upcoming outage of the Open Payments system, in advance of the data submission for Program Year 2018. The system will be down January 3-6 and then again January 14-26. CMS notes that the outages “coincide with enhancements which will enable a better user experience,” but I suspect that they won’t be revolutionary enough to justify 17 days of downtime.

I felt like a fish out of water in my practice this week, as my state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database had some technical glitches. Apparently, connectivity issues impacted the accuracy of the dispensing data for the past week, leaving physicians wondering whether their patients had actually picked up controlled substances more than the website showed. It can be amazing how dependent we become on technology and how much we miss it when it’s not working.

On the other hand, we rolled out some new technology that isn’t working quite as planned and it led to a great deal of aggravation. We switched online check-in platforms and it’s been difficult for both patients and staff to adjust. Our old platform was pretty basic, allowing a patient to provide demographic and insurance information along with a brief history. It also added the patients to a queue so we could bring them into the EHR when they arrived.

The new platform promised much more functionality, including an “appointment time” so that patients can wait at home, avoiding other sick patients and remaining comfortable. However, we’re still trying to see patients quickly as they arrive and aren’t set up to hold an exam room for a patient with a pending appointment time. Despite the wording on the online check-in page, patients have been arriving at the office with the expectation that they’ll be seen at their appointment times. This has led to some friction at the front desks and to a couple of outright confrontations. We’ve been working with the vendor to see if we can change the nomenclature to something like “estimated visit time” or “estimated treatment time” rather than an “appointment time” but it doesn’t look like it can be done.

Our leadership is contemplating going back to the “virtual line” product, which happens to be integrated with our EHR. One of my partners asked about using a system like restaurants use, where a patient can leave the office and be paged when it’s their turn. I have mixed feelings about that approach for patients with infectious conditions. If they’re sick enough to be seen, they don’t need to be moving around the community or visiting retail locations adjacent to our offices.

They’re also contemplating telehealth options, which could help to reduce congestion in the office. I’m personally excited about that option, as flu season makes me dread the inevitable upper respiratory infection I’ll get regardless of how much handwashing I do, and would reduce the number of sick people traveling around the community.

A friend who works at a software vendor clued me in to a recent New York Times piece about our collective obsession with innovation. I was pulled in by its tagline that “some of our best ideas are in the rearview mirror.” It further hooked me with this:

We are told that innovation is the most important force in our economy, the one thing we must get right or be left behind. But the rear of missing out has led us to foolishly embrace the false trappings of innovation over truly innovative ideas that may be simpler and ultimately more effective. This mind-set equates innovation exclusively with invention and implies that if you just buy the new thing, voila! You have innovated. Each year businesses, institutions, and individuals run around like broken toy robots, trying to figure out their strategy for the latest buzzword promising salvation.

That seems to sum up a good portion of the healthcare IT market, especially in the lead-up to HIMSS. There’s a lot of “shiny object syndrome” going on, and by looking for the next buzzword-enriched solution, we may be missing what the article describes as true innovation:

It is a continuing process of gradual improvement and assessment that every institution and business experiences in some way. Often that actually means adopting ideas and tools that already exist but make sense in a new context, or even returning to methods that worked in the past. Adapted to the challenges of today, these rearview innovations have proved to be as transformative as novel technologies.

How many new technologies have hospitals partially implemented that might be revisited to ensure they deliver their additional promise or might be pushed to provide additional benefit for users? Can we glean additional return on our investment or find new uses for it? Are there ideas where some old-school thinking might be of benefit?

The article mentions swings of the pendulum in urban planning and the return of previously marginalized solutions such as farmers’ markets. It mentions the rise of craft beer, heirloom vegetables, and artisan baking as ways that we are moving forward by looking back.

There are plenty of problems that we can solve in healthcare that don’t require technology, and many organizations aren’t even thinking about them. At one large multi-state integrated delivery network, physicians aren’t allowed to delegate refill authority to trained staff even for routine maintenance medications for blood pressure or high cholesterol. Although there are some great systems out there to help with refills (healthfinch, anyone?) an organization first needs to decide that physicians should have support completing those types of routine tasks. Until they arrive at that point, it doesn’t matter what technology is available.

The intersection of technology and policy made me want to scream this week. One of my clients recently changed their password security requirements. I’m wondering if I missed a new release from NIST because some of the requirements are directly contrary to what had been released earlier in 2018. This hospital has adopted some particularly onerous guidelines. Not only must the password include upper- and lower-case letters, it must also include numbers and special characters. They’ve also reinstituted time-based changes every 90 days. Passwords can’t be reused for at least a year. Worst of all, at least five of the eight required characters must be changed for every new password.

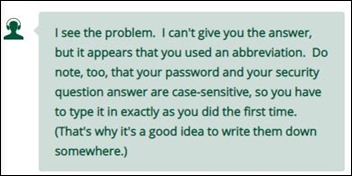

NIST has said previously that requiring periodic changes and arbitrary complexity isn’t helpful for security and that it just frustrates users. On the flipside, the helpful people at LL Bean recommended that I write down both my password and the answers to my security questions. If you’re a hacker looking to score some durable polo shirts or “wicked good” boots, have at it.

Email Dr. Jayne.

It is a screenshot. In some cases they are useful, in others - not so much. In either case we…