EHR Design Talk with Dr. Rick: Keep or Replace VistA? An Open Letter to the VA 4/24/17

Mr. Rob C. Thomas II

Acting Assistant Secretary & Chief Information Officer

US Department of Veterans Affairs

Dear Mr. Thomas:

The decision whether to bring state-of-the-art innovations to the VistA electronic health record (EHR) system or to replace it with a commercial EHR such as Cerner, Allscripts, or Epic will have far-reaching and long-term repercussions, not just for the VA, but for the entire country’s healthcare system.

Several years ago, when Farzad Mostashari was head of ONC, I attended a conference (see post) where he stated that when talking with clinicians across the country, the number one issue he heard was that their EHR was unusable, that "the system is driving me nuts." After his presentation, we had the opportunity to talk. I asked him, given the dominant market share (nearly monopolistic for hospital-based EHRs) that a handful of EHR vendors were in the process of acquiring, where would innovations in usability come from? His answer was that they would come from new “front ends” for existing systems.

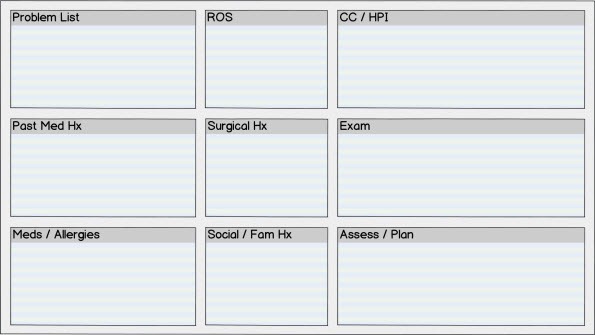

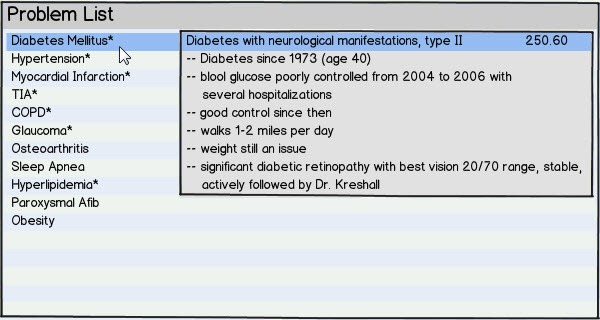

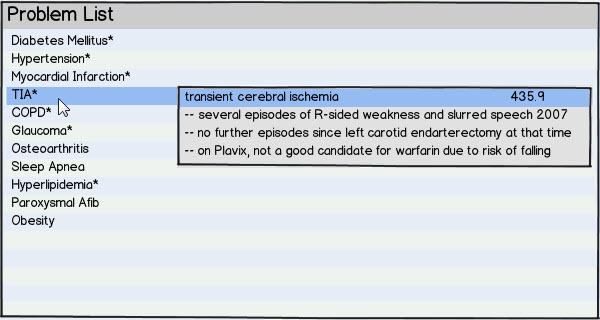

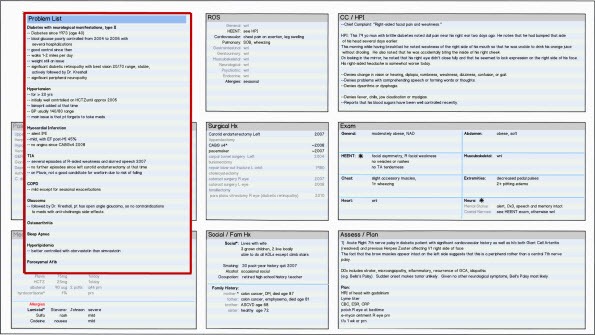

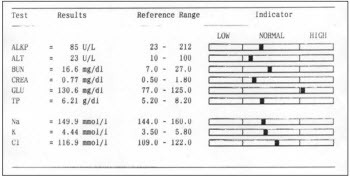

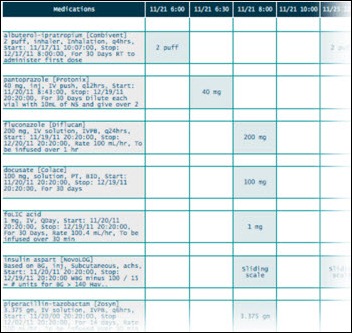

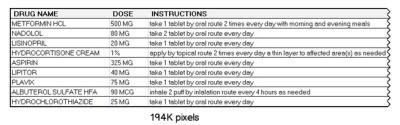

In your deliberations, I would urge you to consider how innovative front end EHR user interfaces, based on the science of Information Visualization, could improve our country’s healthcare system. The field of Information Visualization systematically designs interactive software based on our knowledge of how our high-bandwidth, parallel-processing visual system best perceives, processes, and stores information. Stephen Few describes the process as translating “abstract information [e.g., EHR data] into visual representations [color, length, size, shape, etc.] that can be easily, efficiently, accurately, and meaningfully decoded.”

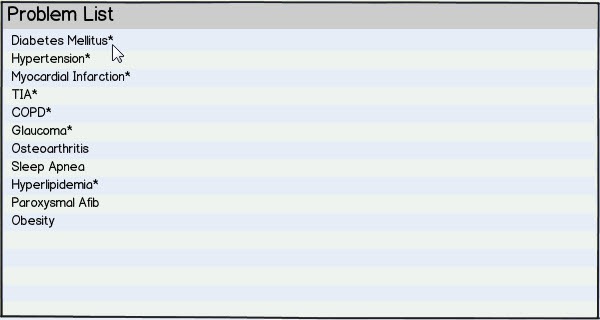

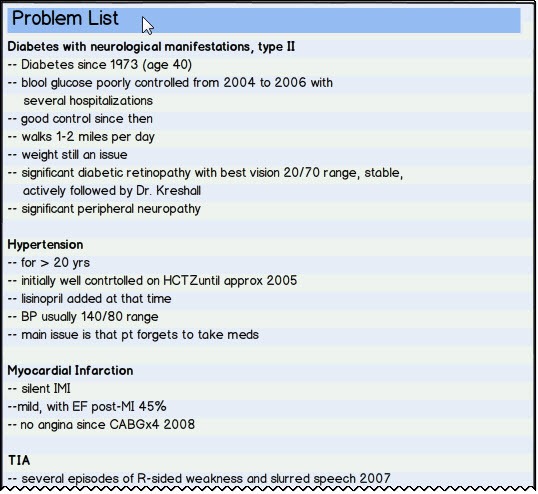

Sadly, while EHR technology has almost totally replaced paper charting over the past decade, not much has changed in EHR user interface design. For a number of reasons, the major EHR vendors have not made it a priority to develop better front ends based on principles of Information Visualization. The adverse consequences for physicians and other healthcare providers, for patients, and for our entire healthcare system are immeasurable. An Institute of Medicine Report found that current EHR implementations “provide little support for the cognitive tasks of clinicians . . .[and] do not take advantage of human-computer interaction principles, leading to poor designs that can increase the chance of error, add to rather than reduce workflow, and compound the frustrations of doing the required tasks.”

A well-known example of an EHR user interface design contributing to a medical error is the 2014 case of Mr. Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, where there was a critical delay in the diagnosis and management of Ebola Virus. No doubt, this case is just the tip of a very large iceberg because most major EHRs use similar design paradigms (and because many medical errors are never reported or even recognized, and even when reported, are rarely available to the public). In the most comprehensive study to date of EHR-related errors, the most common type of error was due the user interface design: there was a poor fit between the information needs and tasks of the user and the way the information was displayed.

Furthermore, current EHR user interfaces add to physician workflow. A recent study found that nearly half of the physicians surveyed spent at least one extra hour beyond each scheduled half-day clinic completing EHR documentation. In addition, current EHR user interfaces frequently fail to provide cognitive support to the physician.

Innovative EHR user interfaces, based on principles of Information Visualization, are the last free lunch in our country’s healthcare. EHR usability issues are becoming increasingly recognized as a major barrier to achieving the Triple Aim of enhancing patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs. Well-constructed EHR user interfaces have the potential to improve the quality and decrease the cost of healthcare while improving the day-to-day lives of physicians. In my opinion, a well-designed EHR user interface would easily increase physician productivity by more than 10 percent, probably by much more, while reducing physician stress and burnout.

On the design front, innovative EHR front end designs, based on principles of Information Visualization, are already being created by a number of research groups, including Jeff Belden’s team at the University of Missouri (Inspired EHRs). See also my design for presenting the patient’s medical record chronologically using a dynamic, interactive timeline.

In addition, technological advances in computer processing speed and programming language paradigms now support the development of a comprehensive, open source library of interactive, dynamic Information Visualization tools. In this regard, see the work of Georges Grinstein and colleagues at the Institute for Visualization and Perception Research at UMass Lowell.

The beauty of building new front ends on top of existing EHR data bases is that the underlying data structure remains the same. This makes the design much easier to implement than if the underlying data base structure and software code had to be rewritten. Fortunately, all of the EHR systems being considered by the VA, including VistA, have excellent and robust underlying data base structure and organization.

The question then becomes, which EHR system is most likely to embrace intuitive visually-based user interface designs and make these designs widely available? In my view, the clear winner is VistA, for the following reasons:

- VistA, unlike the other for-profit vendors, is government owned. Its goal can be to improve the VA’s and the country’s healthcare system.

- VistA became a world-class EHR through its now famous open source model of distributed development, incremental improvement, and rapid development cycles. Using this same model, visually-based cognitive tools for the EHR could be rapidly created, developed, tested, and implemented. Commercial EHRs do not use the same development model and their development cycles are typically much longer.

- VistA is the only EHR in contention which is open source. Any innovative user interface designs developed in VistA would be freely available to commercial EHR vendors and third-party developers and would thereby benefit our entire healthcare system.

- A major federal health IT goal is for EHRs to “be person-centered,” permitting patients to aggregate, organize, and control their own medical records, regardless of the sources. Innovative user interface designs developed in VistA could, with modification, serve as the basis for an intuitive, open source patient-centered medical record.

If the VA’s goal in selecting an EHR, both for the VA and for the country as a whole, is to improve health outcomes, reduce costs and errors, and improve physician satisfaction, then VistA is the clear choice. Any other choice will set our country’s healthcare system back decades.

Rick Weinhaus, MD practiced clinical ophthalmology in the Boston Area until 2016. He writes on how to design simple, powerful, elegant user interfaces for electronic health records (EHRs) by applying our understanding of human perception and cognition. He welcomes your comments and thoughts on this post and on EHR usability issues. E-mail Dr. Rick.

I've figured it out. At first I was confused but now all is clear. You see, we ARE running the…