I'd never heard of Healwell before and took a look over their offerings. Has anyone used the products? Beyond the…

EHR Design Talk with Dr. Rick 11/25/15

Designing a New EHR User Interface: The Paper Chart is the Wrong Metaphor

“New technology demands new representations.” Alan Cooper, Robert Reimann, and David Cronin, About Face 3.

When we are presented with a radically new technology, at first we can’t take advantage of its potential.

Instead, we apply old ways of thinking – old metaphors – to the new technology. Most of the time, the old metaphors don’t work.

In the early days of the automobile, many flawed designs resulted from the fact that at first people could only conceive of the auto as a “horseless carriage.” As a result, many early autos looked and rode a lot like their horse-drawn precursors.

It took a long time for people to stop using the metaphor of horse and carriage when thinking about the automobile. Designers and drivers had to realize that the auto was fundamentally different from its horse-powered predecessor, with its own set of strengths, which eventually included speed, comfort, and reliability. It was only then (and only after we made the commitment to develop an infrastructure of better roads and highways) that innovative auto technology could fully blossom.

Similarly, before the era of EHRs, the paper chart was the predominant tool for organizing and making sense of a patient’s medical record. The paper chart is a powerful cognitive tool, but its strengths are very different from those of the electronic health record. Just as the metaphor of the horseless carriage constrained auto design, the metaphor of the paper chart constrained EHR design, limiting its potential.

The paper chart came in two basic types.

One type of chart, often used in doctor’s offices and other ambulatory settings, was a manila binder where documents of whatever category (notes, labs, orders, imaging studies, reports, procedures, and so forth) were simply added in chronological order to the documents already in the chart.

The other type of paper chart, used in some ambulatory settings and for almost all inpatient care, was a ring binder, with multiple divider tabs which organized documents by category.

New documents were added to the chart first by tab – that is, by category – and then by date.

Both these filing strategies were different solutions to an inherent limitation of the paper chart – a piece of paper can physically only be in one place at a time. Although this physical constraint limited how data in the paper chart could be organized and reviewed, the tangible, physical aspects of the paper chart partly compensated for this filing limitation. For instance:

- Different paper colors and textures were often used to designate different kinds of documents.

- You could easily flip back and forth between two or more parts of the chart without getting lost.

- When reviewing the chart, the documents were right there. You didn’t have to first click on a tab, select a document from a list, and then open it.

- You could flag important documents for future reference by using sticky notes or paper clips.

Unfortunately, when EHRs were first being designed, instead of taking advantage of the potential strengths of digital technology, it was natural to adopt the metaphor of the paper chart. Many of the major EHR vendors adopted one or the other of the filing strategies described above, usually some variant of the latter, tab-based system, where documents are organized by category, and only then by date.

Surprising as it sounds, what this means is that if you are using Epic or Cerner or many other EHRs (at least the way they are usually configured), you can’t do something as simple as get a single date-sorted list of all clinically relevant documents.

In the era of paper charts, if you were using the tab-based system, this was just a fact of life. A physical document could only be filed first by category or first by date.

There is no such limitation, however, with digital documents. From the user’s point of view, a digital document can, in fact, be filed in two places at the same time. To retain the old paper chart metaphor when designing the EHR user interface makes absolutely no sense. The antiquated metaphor constrains and limits the design.

Now you may figure that this is not really a major issue – that it shouldn’t make that much difference whether an EHR organizes a patient’s documents first by date or first by category. But remember that if you are a doctor, nurse, or other care team member, as part of each visit, you are going to need to review the patient’s history, especially the interval history – what occurred since the last visit.

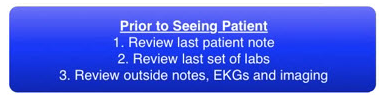

Consider the workflow below, recommended in a training video for a major ambulatory EHR which, like Epic and Cerner, uses a tab-based design to organize the patient’s documents by category.

Much has been written about the time involved and the number of clicks required by most EHRs to accomplish this kind of task. I believe, however, that an even bigger problem is the cognitive burden a tab-based design imposes.

First of all, most tab-based EHR user interfaces violate a basic principle of interaction design – that of visibility. Specifically, until you click on a tab, you can’t see which documents are present or even if any exist.

Second, working with lists of dates in numeric format is cognitively challenging.

Third, when switching back and forth between documents stored in multiple tabs, you expend working memory keeping track both of the chronological order of the documents you’ve reviewed as well as their subject matter. There’s not much left for interpretation.

Unless you have experienced first-hand what it is like to review chart after chart, day after day in this manner, it’s hard to fathom how this kind of needless cognitive effort interferes with patient care.

The point is that EHR user interfaces do not need to be constrained by the old paper chart metaphor. The digital nature of EHR technology allows us to design better, albeit different user interfaces.

For instance, in addition to simply being able to switch back and forth at will between displaying documents by date or by category, digital technology can support:

- Graphically displaying both the chronological order and the subject matter of documents by using an interactive timeline.

- Using color, shape, size, and location to encode information visually, allowing us to use our high-bandwidth visual processing system to perceive much of the data.

- Acquiring detail with a simple mouse hover or comparable touchscreen gesture.

- Animating navigation to help the user stay oriented in information space.

- Displaying detail plus context on the same screen.

I have long proposed that most doctors use a chronological mental model in thinking about the patient – the patient’s history should unfold like a compelling story. Furthermore, displaying information graphically shifts the balance of mental effort from cognition to perception, sparing cognitive resources for patient care issues.

If this is the case, compared to using current tab-based designs, a timeline-based, graphical user interface for the EHR should make it easier for doctors and nurses to review, explore, navigate, and select EHR documents.

In my previous post, I proposed an EHR user interface design of this nature, The EHR TimeBar. For those readers who have not yet seen the design or who would like to review it in connection with today’s post, it is described in the document below. Although the TimeBar design displays documents in chronological order, it also supports both searching and filtering by category (see pages 19-22).

The document above describes the EHR TimeBar. Click the two-headed arrow bar icon to display it full screen since it will be hard to see otherwise. It can also be downloaded as a PDF file here.

Next Post: Telling a Story on a Timeline

Rick Weinhaus, MD practices clinical ophthalmology in the Boston area. He trained at Harvard Medical School, The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and the Neuroscience Unit of the Schepens Eye Research Institute. He writes on how to design simple, powerful, elegant user interfaces for electronic health records (EHRs) by applying our understanding of human perception and cognition. He welcomes your comments and thoughts on this post and on EHR usability issues. E-mail Dr. Rick.

OK I don’t want to be a shill for Epic, but in that environment I can easily look now at all the documents in time order or select individual tabs. As a procedural specialist I’m often more interested in who the authors are, and there’s a filter feature that lets me quickly find what I’m looking for if it’s a fat record, be it who the author is, op notes, etc. I’m not gainsaying your timeline concept, but the informational Achilles heel here isn’t labs, meds or other granular elements–they’re fine now. The problem, and very much the horseless carriage you refer to, is the individual “note”, which remains a deeply siloed sinkhole of information, especially in the hands of specialists, most of whom refuse to deal with the structured data entry elements the EMR offers. Medical minds themselves need to change, and develop an object-oriented type of contact documentation, with documentation solely of the additions and changes to the ongoing record generated by the contact.

I am a newer doctor (just finished fellowship) and I have different thoughts. I don’t understand why the clinical record needs to have tabs and paper. I believe it is an issue with more experienced doctors not ready to change their ways.

To take Dr Rick’s example forward, it feels that having older doctors expect an EHR like a paper chart is no different than the horse carriage drivers using the same process to drive an automobile. I believe we as doctors need to change and learn how to use these tools for the patient’s benefit rather than complaining about how it doesn’t work the way we were taught in medical school or how some of us have practiced for decades.

EHR TimeBar is a fabulous idea. Thirty years ago in earning an IT concentration MBA, a clinical decision support tool became a personal dream. As everyone knows EHRs as they exist now are not it, in spite of the cliched dashboards. TImeBar is a great approach to laying out a dimensional structure. From the perspective of primary care, the other dimension to map for cognitive efficiency is the depth of detail, “granularity”. First encounter we do not need all the lab values, just “Mr. Jones achieved adequate control of his AODM over the past year after he was initially diagnosed in 2013.” That kind of of overview with an associated drilling down sounds like the need for some natural language. Good luck, Rick–I look forward to hearing more refinements to your user interface.

Amen! I seem to remember a great Steve Jobs quote… “If Henry Ford had built what his customers wanted he would have built a faster horse…”