Curbside Consult with Dr. Jayne 8/10/15

The continued consolidation in the EHR market is often a cause of concern for physicians and hospitals that haven’t chosen the dominant players. There are still plenty of specialty-specific of niche products out there that are certified and do a great job and their users may not be looking for a change. For those groups on a mid-sized system or looking to participate more actively in value-based care programs such as accountable care organizations, the desire to move is much more tempting.

I’ve written over the last year or so about how my own health system went through the process. It was very organized and quite transparent, with all kinds of end users and technical staffers participating in the process. An initially large vendor list was narrowed to three. Then structured analysis of the products was performed. Ultimately we had on-site demonstrations and a variety of metrics were assessed and scored for each of the vendors to assist in the final decision.

We knew we had a handful of existing vendors that would be de-installed regardless of the final selection. We communicated our intent with them throughout the process. We worked with not only our designated front-line support team, but also with vendor executives to help them understand the forces that led us to the decision to sunset their product.

It was dicey at times, because even though we ultimately decided on a single vendor for ambulatory and inpatient clinicals, we ended up keeping another vendor’s enterprise financial system for inpatient. We were clear about our needs and what we felt were challenges with keeping any other individual systems and made sure that our vendors knew where we stood at all times.

Although until recently I’ve spent most of my CMIO career within a single health system, I’ve collaborated with many other CMIOs as we shared our struggles and victories. I’ve seen the system replacement process through at least half a dozen different lenses as colleagues have worked through the process. It’s always been fairly collaborative with the vendors much as my own experience was. With that in mind, it’s been interesting to watch one of my friends’ hospitals go through a fairly hostile system selection process.

He’s always been a bit of an outsider, a CMIO without the title who the administration grudgingly put into place when physicians complained about the poor quality of the EHR. Although he didn’t have formal CMIO training, he’s taken the proverbial bull by the horns the last two years and really made a place for himself. He’s led the charge for overhauling their EHR governance and standardizing the system. This has allowed for retirement of customizations that were crippling workflow while improving physician satisfaction. Training quality has improved and the IT teams have been restructured.

I’ve been mentoring him on how to work with his vendor to help his hospital move forward. Initially the primary EHR vendor (which we shared at the time) was being blamed for everything, regardless of whether it was actually relevant. I reviewed and critiqued some of his strategies for helping the users understand that a lot of their pain was self-inflicted and supported him through a couple of upgrades which he used to steer workflow to a much better path for everyone.

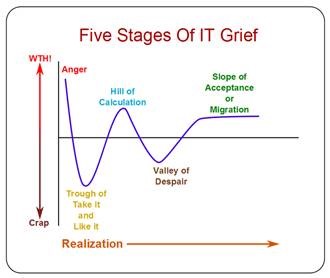

Knowing how hard he’s worked to improve relations with his vendor, I’ve also watched his pain as the hospital decided to migrate off the system. He’s shared some of the email threads with me as a way to vent his frustration, so I know he’s not exaggerating. The vendor was told several months ago that the hospital was looking at a potential system replacement (largely due to a failed hospital implementation of a different vendor) that would also potentially impact the ambulatory systems. Rather than be honest and open about the process, the hospital appeared to ignore the vendor’s attempts to be kept in the loop. My friend has been increasingly frustrated at the way his administration is acting, but they’ve made it clear that he doesn’t have a seat at the table.

Most frustrating is their complete disregard for the end users in this process. They haven’t done any significant engagement of physicians, nurses, or other end users. They haven’t done any demos or site visits. Instead, they went ahead and contracted with a different vendor behind closed doors. Even more offensive is that my friend found out that a contract had been signed when he saw the press release. I feel bad for my friend – that kind of treatment is just inexcusable. But I also feel bad for our formerly-mutual vendor.

Sometimes I guess customers forget that vendors are people, too. Even if you don’t want to continue to do business with a company, hopefully you have developed at least some semblance of a relationship with the people who support you and work with you on a regular basis and may have done so for years. It would be nice to let them know of your decision before a press release is issued or before they read about it on HIStalk with their morning bagel. I’m aware of the adage “it’s just business,” but sometimes it also needs to be personal. After all, we’re people.

Some of my best friends in the healthcare IT space work for vendors. Getting to know them and understanding how things work on the other side of the stream (or river, or gorge, depending on how well you mesh with a given vendor) has made me a better CMIO and a stronger advocate for my own users. Many of them have gone to work for other vendors in the industry, allowing me to be exposed to different strategies and technologies that I might not have known much about while working at Big Health System. They’ve definitely helped me be a stronger contributor to HIStalk (even though they may not know it) and for that I’m grateful. I feel sad whenever one that I’m close to moves on. I sincerely hope that our paths cross again.

I’m sad for my friend (and his hospital) and also for the vendor and its team. I hope that there is more transparency during the actual migration project, for everyone’s sake. Whether the relationship is working or not, it’s still a relationship.

Have you hugged a vendor lately? Email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

RE: Surescripts survey finds that more than half of of patients have experienced delays or disruption in getting their prescriptions…