Angie Franks is president and CEO of Central Logic of Sandy, UT.

Tell me about yourself and the company.

I am a healthcare technology veteran. I’ve been in the tech industry for over 30 years. I found myself in this position as CEO of Central Logic after serving on the board for close to four years. The board made the decision to take the company in a different direction and it was a good time for me, career-wise, to step in. I don’t think I’ve ever had more fun than what I’m doing today.

I like to use a couple of phrases. One is healthcare access and orchestration. It’s about moving patients into the health system via acute care, inter-facility patient transfers. Think about a patient who is in a rural facility or one that doesn’t have the appropriate level of acuity to take care of their needs. They need to be moved to a facility that is more appropriate for their condition. We take all the friction out of that process and make it easy to move a patient from one place to another.

What is the process involved with moving a patient from Facility A to Facility B?

With or without our system, it’s always a phone call. The sending physician and the accepting physician get on the phone and have a conversation about the patient to make sure that the patient is in a state where they can be transferred safely. Because the minute the accepting physician says, “Yes, we will take the patient,” they are responsible for that patient’s care until they get to the receiving facility. They are then part of the care team for that patient. If something happens to that patient, you want those conversations documented and recorded.

Without our system, there’s a phone call to the hospital system, into a call center, transferred around, bounced around, nursing station, phone calls back, lots of time delays, and a back-and-forth process before you can get to a decision of, “Yes, we can make that transfer happen.” When you put in technology, workflow, process, and access to data that we enable, you can take what might have been 10 or 15 phone calls and three hours to get a patient transferred down to a phone call or two and 10 to 15 minutes.

What does the receiving hospital review, other than clinical information, before deciding whether to accept the patient?

A transfer center agent takes the initial call. It’s a clinician, usually a nurse, or it could be an EMT. They identify the physician on call who should take the call and make the decision.

There’s the whole clinical piece that you just referred to. Where does the patient need to go based on the condition that they have? Then, do we have availability in this hospital or somewhere else in our system? Identifying that location, making that decision to say, “We’re going to place the patient in this bed, so hang on to that bed for this incoming patient.”

Then there’s the logistics of how we physically move the patient to the system, ordering the transport and getting all of the logistics done for the physical move.

Enabling all of that through one phone call and one number is what we do. When your health system makes it easy for other health systems or for other providers to send an acute care patient to you, you become the first phone call they make every single time. At the end of the day, this is a revenue-generating function for a health system. It helps bring in patients, it brings in the patients they want to bring in, it brings in the right level of acuity to support service line strategies or whatever the growth strategy is for that health system. When you make it easy, the sending facilities call you every time.

What are the primary sources of inpatients other than a hospital’s own emergency and surgery departments?

There are three primary sources — the emergency department, scheduled procedures, and the transfer center. When you don’t have a transfer center, a greater mix of your inpatient admissions come through the ED, which is a reactive way of building volume and driving patients into your health system that you seek to acquire and retain.

When you put a transfer center in place, you start strategically shifting the mix of patients that you have coming in the front door of the health system. More of those patients come in through your transfer center from other facilities that don’t have the ability, the room, or the capabilities and then send those patients your way.

It’s very attributable. It’s a tremendous ROI for every patient who is transferred into the system. When we work with health systems, we look at their current benchmark or baseline volume of transfers and compare that to where they should be given their size and their demographics. We can accurately predict the growth impact of putting in a transfer center, within a narrow timeframe on when they’ll break even on the investment for this type of solution. We can tell them what the net contribution margin impact will be in Year 1, Year 2, and so on.

In the entirety of my healthcare tech career – EMRs, ERP, and physician practice management — it was always a message of better, faster, cheaper. You’re trying to sell an intangible, the soft ROI of efficiency. This is the only time that I can truly say the value proposition that we bring to the health system can be forecast financially and and attributable down to a patient. It’s easy to track and document.

From a clinical perspective, you get superior clinical outcomes when you get people to the care that they need in an efficient timeframe. The patient’s life is in the balance when you’re in the midst of a transfer. These are not healthy people who just need a referral. These are people who are really sick, and they’re sitting in a facility where they can’t get the care that they need. When you can shave an hour or two or even 20 minutes off that transfer time, it can mean the difference between life or death for the patient, or it can mean the difference between a high quality of life after they’ve come through this medical situation and something much more compromised.

How will expanding health systems and the move to value-based care change how health systems manage their available beds?

As we make that shift to a more value-based care environment, this is all about giving the facility and the health system more control over helping the patient or their provider make the best clinical decision as to where that patient needs to be for the care that they need. You can’t manage and control that for high-acuity patients without the transfer center. Otherwise, who is coordinating the care? What is the fulcrum or the point inside that health system for helping make the decisions that are in the best interest of the patient and the system’s capabilities to deliver appropriate care? This is the function inside the health system that would make those decisions in a value-based care model.

I would add that the data that is captured inside of the platform, the technology that we’re providing, is so robust that it allows the health systems to make strategic decisions about capabilities that they should be offering, geographic areas that they should be serving better where transfers are coming or demand is growing, and services that they’re getting asked for that they don’t have the capability to deliver or maybe that have a higher demand than their ability to deliver. It’s a myriad of data elements and trends that allow executives, typically the chief strategy officer, to make strategic decisions for service line offerings for their health system or geographies that they should be serving.

What clinical information does the receiving hospital get from the sending hospital?

The information that is captured comes form the call from sending physician to accepting physician or to the clinician that takes that call. The Central Logic technology becomes like the EMR for that patient transfer. It’s all of the medical record around what status that patient is in when the call comes in. We have clinical protocols built in so you can rapidly capture all of the information about the patient’s current state and any other key clinical information that is relevant, and then the call between the two physicians. All this information is recorded and codified and a summary of that entire transfer record is passed as a PDF into the EMR. There’s always a record of the entire transfer end to end.

That has some pretty significant liability issues associated with it. If you don’t have these calls documented and you don’t have the entire decision-making process captured, you are opening up your health system to exposure to EMTALA violations. Also, oftentimes you can’t document in the EMR for a patient who doesn’t have a chart in your system, and most transferred patients are new to the health system. You’re exposed if something bad happens when you decline a transfer and you don’t have a way to document that the call came in. If the patient’s family sues the health system for denying the transfer and the patient passes away — and we’ve seen cases like this — and there’s no documentation that the call ever happened by the accepting facility, you can be liable for that decision with no documentation to back up why you made it.

You want and need to have a place where you can accept the call, document the condition, save that information, record the conference call between the physicians, and then maintain that record for the longevity of the patient, either in the patient’s chart or in the transfer record transfer system, in the case of of a denied transfer.

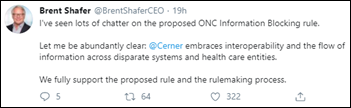

We talk a lot about interoperability, which often means sharing past visit records when a patient presents to a different facility. Does the receiving facility get the patient’s active chart, or something like it, from the sending hospital so they don’t have to start over and repeat tests and trying to understand a situation that has already been analyzed?

I just wish that we were at a place, interoperability-wise, where that was seamless. But the reality is that it just does not happen in today’s world. The information would have to come from the sending facility’s EMR. We have to inter-operate with just about everybody because it is fundamental to what we do. We’re talking to parties inside and outside the walls of the health system to facilitate a transfer on every single call. We have had 10 to 15 million patient transfers through our platforms. To broker the data back and forth between the the sending facility’s EMR and the accepting facility is not a problem technologically, but we’re just not at a point in the industry where the systems talk to each other like that. I’m going to just say that in today’s world, that does not happen. It is the information documented on the call.

I have to admit that in my entire health system career, I knew nothing about hospital-to-hospital patient transfers. They always just looked like admissions.

I would echo what you just said. After 30 years in the industry, until I joined the board, I had never even heard of a transfer center inside of a hospital. In fact, it never occurred to me to even think about how patients get to the hospital for the care that they need, outside of the emergency department and scheduled procedures. This is a channel strategy for health systems, but it’s not intuitive. It’s not something that we think about.

Do you have any final thoughts?

We’ve probably had more of a, ”If you build it, they will come” mentality in health systems. This is a more retail-like mindset. “We built it, we have the plant and the facility and the delivery capabilities, now go out and get the patients in the door who need to be in our health system.” It’s a big financial reward and a clinical outcomes reward for that patient and a much better clinical outcome for the individual. We make it easy.

Comments Off on HIStalk Interviews Angie Franks, CEO, Central Logic

I generally follow AP Stylebook style guidelines: Do not use all-capital-letter names unless the letters are individually pronounced: BMW. Others…