Tell me anything interesting you’ve seen or heard since I need to plan my Wednesday and possibly Thursday if I don’t skip out.

I was standing outside in the cold barely after sunrise this morning, wondering where the HIMSS shuttle would be stopping since it wasn’t marked on the street. The HIMSS app wasn’t updating the bus status, and when it finally did, it showed a 15-minute wait on top of the 10-15 minutes I had already waited, so the planned 15-minute intervals didn’t actually happen even in light traffic.

I got my badge quickly, took a stroll around (my IPhone says I took 22,000 steps Tuesday by mid-afternoon), and then waited around for the exhibit hall to open at 10 a.m. I realized afterward the apparent extinction of the ball cap girls who used to forcefully thrust the show daily from Healthcare IT News at every passerby, almost defying you not to take a copy that you didn’t really want.

I also noted that the Starbucks line stretched endlessly and never died out completely, even in the late afternoon when I can’t imagine wanting coffee of any temperature.

My first action was to hike what seemed like miles to get a look at the lake and skyline. It was a beautiful, spring-like day that quickly erased memories of yesterday’s snowy gray.

Tell me without telling me that the HIMSS conference is in Chicago this year.

I saw this guy outside the exhibit hall. I saw a couple of other dogs in or near booths and HIMSS had a puppy play area that was being used to solicit donations for The Anti-Cruelty Society, although I disappointingly didn’t time it right to seem them playing in their fenced-in yard.

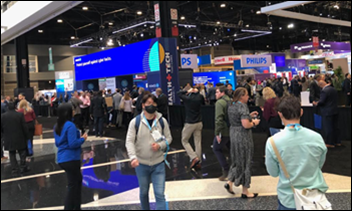

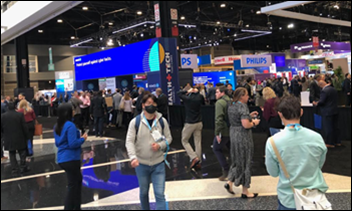

This is either (a) HIMSS23 attendees right before the exhibit hall doors opened, or (b) runners awaiting the starter’s pistol in the Fairly Well Dressed 5K. I have zero fashion sense or interest, but bright brown shoes and tight suits or blazers over jeans are current looks that look better than the baggy, three-piece charcoal gray suits and mirror-polished black shoes of yesteryear.

This is the first HIMSS conference that felt normal by 2019 standards. People were everywhere, almost nobody wore masks, booths were laid out with slightly wider aisles but normal spacing otherwise, and I didn’t see a single elbow bump in lieu of a handshake. Most of the hygiene theater of the dark ages of 2020 and 2021, which was of questionable scientific merit even then, has since been proven pointless and was quickly abandoned.

HIMSS says attendance is already up hugely over 2021 and nearing 2019 levels, but then again, why wouldn’t they say that when we “trust, but verify” types can’t investigate whatever number they throw out there? Regardless, the increase feels directionally correct. The exhibitor list shows 1,215, although some of those companies bought only meeting rooms rather than booths.

I started out with a packed ClosedLoop.ai session in the north hall. The anchor booths were in the south hall, but a few bigger vendors got the north hall, including Google Health.

Nice color coordination, Orion Health. I like it.

I attended a Sodexho presentation on having hospital staff initiate conversations with patients and then report back through the company’s Experiencia tool, which gives executives a real-time dashboard and alerts of patient issues while they can still be fixed. They said that nobody likes filling out a survey, especially if it’s likely nothing will happen anyway, so they use in-room conversations and text messaging to let staff either resolve or explain a problem, freeing up clinical staff who would otherwise be dealing with the hotel side of being hospitalized.

The exhibit hall was full of bare floors, weird dead ends, and unattractive HIMSS ghost town spaces. Tegria got a terrible location that was nearly impossible to find even when following the hastily erected directional sign, and Ellkay had a “this way” sign several aisles over like a highway exit. That reminded me of a HIMSS conference years ago in Las Vegas, where the downstairs Hall G was drawing so few people that HIMSS was shamed into adding extra signs and offering lunch discounts for enticing visitors to head downstairs into what resembled a poor student’s basement rumpus room.

The Microsoft-Nuance booth was busy.

I overheard several folks lamenting, as was I, the apparent end of an era, as Oracle has apparently expunged the Cerner and Oracle Cerner names in favor of Oracle Health.

I went to a session about the CoMET AI-based patient monitoring solution by Nihon Kohden by the doctor who developed it. He mentioned an interesting fact from a study – training a sepsis model on a hospital’s surgical ICU data had zero predictive value for the same hospital’s medical ICU, and vice versa. Models don’t work if they were trained on data from multiple hospitals or even multiple areas of the same hospital. I’m curious why that would be, so I’ll have to dig up the paper.

I think ChatGPT’s straight vertical growth and endless publicity have HIMSS23 vendors too little time to feature generative AI in their booth materials, other than EClinicalWorks anyway.

Giveaways were interesting this year. I forgot my battery-powered phone charger that I got at a HIMSS conference years ago, but nobody was handing them out. Chapstick and stress balls were in limited supply. I did score some Garrett’s popcorn, however.

Someone asked me, “Do you want a beer” from a booth at barely past noon, which I answered in wondering if the question was rhetorical given the hour. The person at the Silex booth assured me, “You wouldn’t be the first person to say yes,” so I took one from the ice chest to sip as I watched another vendor’s presentation. I’m sure the price they pay the concessionaire for each beer is astronomical, so I made sure to enjoy it.

You pay thousands of dollars to attend a conference, another $20 for a prison-grade lunch, and this as your seating choice if you want to eat, charge your phone, or allow your introversion to be soothed. I really don’t understand why we as attendees tolerate this. It isn’t like Las Vegas, where everything revolves around keeping you in the casinos, so putting out more tables and chairs surely wouldn’t upset the business model. I’m sure McCormick Place has buildings full of unused furniture.

The going-home Red shuttle line was pretty poorly marked in the convention center halls, so I finally found the bus after a few wrong turns and near-constant doubt that I was in the right place.

A Chicago reader agreed with my assessment that deep-dish pizza is awful (not my style, as El Presidente would say) and suggested tavern style instead, a Midwest-only specialty that I unfortunately haven’t found in River North that seems to favor Neapolitan style at steep prices. However, that person also urged me to go to Al’s or Portillo’s for Italian beef, so I left the convention center early, walked over to Al’s Italian Beef on N. Wells, and had a wet beef with sweet peppers and a large side of perfect hand-cut fries. I heard people talking all day about the sumptuous dinners their employers would be underwriting Tuesday evening, making me even happier with my self-paid $15 one that I consumed with gusto away from other badge-wearers. All that was missing was a working man’s ice-cold draft PBR or Heileman’s Old Style.

Conversations Overheard

A lady said she decided not to renew her membership in women’s group Chief because it was going to cost $9,000, which she was paying out of her own pocket, and she felt that the two women who started the organization made an unexpected fortune but didn’t deliver much afterward. She told someone that the organization had done nothing that benefited her in one year of membership.

Someone said that a few CIOs told they they were going to stop attending the HIMSS conference in favor of ViVE, saying that HIMSS didn’t recognize the threat of having its CIO track at HIMSS turned into CHIME’s own conference. The person said that the HIMSS conference would become an event for provider managers and directors who might then report what they learned about vendors and products to the decision-maker back home, to which I responded was often the HIMSS model anyway since CIOs often don’t roam the floor and instead dispatch underlings as scouts.

Most of the common hallways of the exhibit hall were uncarpeted, exposing spray-painted labels, hazard tape covering wires, and metal plates in the floor. Apparently Hal Wolf said in the opening session that it was an environmental decision based on the need to otherwise manufacture, install, and dispose of carpet. Sort of the same argument that hotels use in trying to convince you that re-using your room towels is for the environment’s benefit, not their own.

A top vendor executive emailed me today to say, “I hope you will be writing about the absolutely pathetic bare floors across the halls here at HIMSS. Vendors are required to pay for flooring in our booths (carpet, vinyl, wood, etc.) but HIMSS felt they didn’t have to do it? Ridiculous. We have never exhibited at an event where the exhibit hall felt incomplete until HIMSS23.“ I agree, and the environmental excuse seems iffy given the carbon footprint of endless flights for an in-person event compared to every other conference that somehow manages to lay down carpet. It’s beginning to seem like this was a “recover financially from HIMSS20” year for HIMSS in staying home in Chicago for making the exhibit hall look like a underfunded indoor flea market. I’m curious if anyone has seen other examples of apparent belt-tightening.

A long-time reader checks in: “Judy Faulkner recommended HIStalk to 30 of us in a conference room when she taught us about the ‘Epic culture’ in 2003. I have read every week, nearly 20 years! Thank you for writing.” Thank you for reading. My insistence on remaining anonymous and avoiding self-promotional activities means that HIStalk to me is an empty screen in an empty room, and writing it feels like scrawling in a diary that I don’t intend for anyone else to read. I like it that way, but I appreciate those few times each year when someone shares what their side of my screen looks like since I have no idea.

Someone asked if anyone was hearing anything about HIMSS Accelerate. Negative.

News

The VA’s Oracle Cerner system goes down for five hours on Monday, apparently joined by the same downtime for the DoD’s instance of Oracle Cerner.

Memora Health gets a $30 million investment from investors that include General Catalyst and two big health systems.

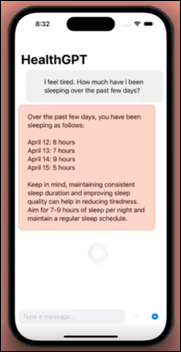

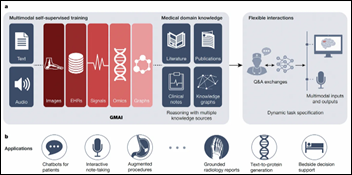

A recent Stanford computer science graduate creates HealthGPT, a test case for connecting generative AI to Apple Health data to support answering user questions, such as, “How should I train for a half marathon?”

Fun framing using Seinfeld. Though in a piece about disrupting healthcare, it’s a little striking that patients, clinicians, and measurable…