Curbside Consult with Dr. Jayne 10/1/18

I occasionally do a little bit of work for a local personal injury attorney. It’s not the big-time expert opinion work you hear about physicians doing on the side, but more of a translation service. Basically, I take hundreds to thousands of pages of printouts from EHRs and try to reconstruct a coherent timeline of what happened and who documented which data, so that the legal team can understand the facts of a case and determine whether they have something they want to take forward. At least the printouts are virtual, and I’m sifting through PDFs rather than dealing with boxes of documents delivered to my door.

I worked on a case over the weekend from a local hospital where I have never been on staff. The most striking part of the assignment was the poor quality of the records.

The case involved a “routine” outpatient surgical procedure that ended in the patient’s death. The entire episode of care lasted barely more than 24 hours, but there were six different PDFs sent, ranging from 20 pages to 370. Although all the notes and entries were electronically signed by the pertinent physicians, it was quickly apparent that the physicians hadn’t really read the notes before authenticating them. Either that, or they read them and just have a passing familiarity with the idea of matching the pronoun to the gender of the patient or ensuring that the note actually makes sense. Especially since this episode of care contained a profound medical misadventure, one would think that the attending physician (who was going to receive attribution for the case) would have made sure the key portions of the record made sense.

The hospital had numbered the PDFs from one to six, and I quickly realized that the numbering was not at all related to what one would expect in a typical chart. Each file contained a mixture of timelines and care locations (pre-operative area, operating room, intensive care) and was so confusing that I actually thought about printing the whole thing out so I could sort it into chronological order. The admission history and physical was in the middle of the third file, and the discharge summary (also known as the death note) was in the middle of the second. It probably would have been better if the discharge summary was at the end of the last file, because after reading it, I was so aggravated that I had to take a break.

Although the document was clearly identified as a death note, it also contained “Home Instructions for the Patient” and a list of “Medications You Should Continue at Home.” I imagined myself as the widow of this patient reading that and how insensitive it must have seemed to her. She had requested the records personally and provided them to the attorney after she was unable to get answers to her questions from the hospital’s risk management team.

I imagined how confused she must have been by the six files, how disjointed they were, and why she felt she needed to ask the hospital for clarification because the records didn’t make sense. I also put on my EHR hat and thought about how easy it would be to have a separate template for the death note that didn’t have those components that only apply if a patient is actually leaving the hospital.

When I finally made it to the physician notes, I noted how poorly the history of present illness (HPI) was written even though it was either dictated or typed as free text. The patient had been transferred from the operating suite to the intensive care unit after being emergently intubated and placed on a ventilator, which the HPI described as “the patient was difficult to breathe.” The patient was referred to twice as “her” and the rest of the time as “him,” the latter of which was appropriate. Another physician note said that the patient had been “electively intubated for the outpatient procedure” which was incorrect, which somewhat makes one question the accuracy of the documentation in general.

The nursing notes were also interesting, with a nurse documenting that a fall risk assessment was performed and “the patient verbalized understanding” despite the patient being paralyzed, sedated, and on a ventilator, with a documented Glasgow Coma Scale of 3 which basically means the patient was nonverbal and unresponsive to verbal or painful stimuli. One can perhaps blame that one on a macro or shortcut being used, but as a healthcare provider I was embarrassed to see it. The patient also had a “weapons assessment” performed upon arriving to the intensive care unit, although I’m not sure how he could have become armed after being assessed similarly in the pre-anesthesia care unit and having been unconscious most of the time. I understand the value of checklists, but it was just one more thing clogging up the notes that didn’t make sense.

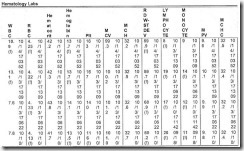

I was heartened to see that the hospital was using a virtual sepsis protocol and remote ICU services from a tertiary care center. My enthusiasm was curbed, however, when I reached the laboratory data section, which displayed the data in an extremely hard-to-read grid (above). I can’t imagine that there was much clinical input on or approval of that document before putting it into the system, and if there was, would love to have a conversation with whoever approved it to go into production. I’m sure users are reading the data on a screen with a scalable display in real time, but it’s still important to be able to have a printout that makes sense.

The attorney who sent me the case felt that there was not likely a valid claim, but had asked me to review to help provide answers to the family. Even in that context, I always review to see if there was an element of negligence or substandard care. I wasn’t pleased to see that the consent for surgery document didn’t have the patient’s name filled out or the surgeon’s name completed in the respective blank spaces. It did have a patient sticker and MRN on it, but not using the blanks as designed just makes it feel like either someone was in a hurry or someone didn’t care, neither of which are great when there has been a poor outcome.

The bright spots of the entire chart were the chaplain’s notes. They were free-text narrative, and although I couldn’t tell whether they were dictated or typed, they were cohesive and actually told the story of what had happened to the patient far better than the physician progress notes (each of which was 8-10 pages long because they contained copy-and-paste content from previous notes). The chaplain’s notes also contained detailed summaries of what was discussed with the family and their responses to the information provided. Those chaplain’s notes were probably the most solid piece of documentation in the chart and they illustrated that the clinical team acted within the standard of care after the initial event.

In the healthcare IT world, we think of projects and timelines and budgets and deliverables, but often we struggle to find the time to think about patients and their families and how those individuals would view our efforts. This family probably doesn’t think very much of the quality of records at this institution and I know the attorney doesn’t either.

As a CMIO, a patient, and a family member of patients, I’m appalled by what I saw. We can do better, and our patients deserve it.

I’d like to throw out a challenge to readers. Take a look at the documentation your systems are producing. Find a death note or a discharge summary with an outcome of “deceased” and see what’s in it. Make sure that you are producing documentation that you would want a patient’s widow or child to see. If you’re a vendor, take a look at your document production code and see if you’re contributing to the problem or helping to solve it. I challenge you to find the development budget to make these issues right if you’re the cause.

Do your users read and correct their notes, or just sign them? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Fun framing using Seinfeld. Though in a piece about disrupting healthcare, it’s a little striking that patients, clinicians, and measurable…