Curbside Consult with Dr. Jayne 11/30/15

I wrote last week about open enrollment for health insurance and other benefits. A reader sent me this screenshot of his company’s enrollment management system, giving it an “F” for usability. Although the rolling hills are probably supposed to calm employees before they see what their premiums will be this year, the fact that they obscure half of the labels is likely to increase anxiety. Not to mention, can you trust a company that doesn’t care if you can read the password requirements or not?

Another reader wrote about the expanding list of employee-paid options his company offers. In addition to medical, dental, and vision insurance and flexible spending accounts, employees also had the option of choosing pet insurance and a legal services PPO.

I admit that I don’t know anything about contract legal services, but found it kind of funny that lawyers would start down the slippery slope that got physicians to where we are today. We’ve seen what having third-party payers has done to the healthcare system and are still trying to cope with payments that are spiraling down while insurance company profits continue to climb. If anyone has inside knowledge on this trend, I’d be happy to run comments.

Nearly everyone I’ve talked to about open enrollment and health care coverage has mentioned that they get either a premium discount or a penalty (whichever way you look at it) depending on the presence or absence of certain health-related behaviors. Anecdotally, the most common are discounts for being a non-smoker or participating in a smoking cessation program.

Close behind are discounts for having certain lab screenings done, although the results aren’t taken into account. My former employer required lab screening for all employees to get the lowest rate, regardless of whether the labs were evidence-based or indicated. Although I’m sure they got a volume discount for having the lab work done, the concept of coercing people into having screening tests isn’t exactly driving down the cost of healthcare.

Looking at my former team (which was fairly young), only 20 percent of them were in an age bracket where the blood work was actually indicated. I’ve had plenty of conversations with Medicare patients who want a specific test regardless of whether it’s indicated simply because “Medicare covers it and I’ve earned it,” which is no way to practice medicine. Seeing this type of behavior reinforced by private payers is disappointing.

The other troubling thing about the whole business is the aspect of coercion. Those of us who believe in evidence-based medical care have spent our careers trying to order the right tests for the right patients at the right time, not just doing things because they’ve always been one way or another. Even simple laboratory tests are not without risk. There is a chance that they will uncover an “abnormal” but irrelevant value that will lead to patient distress or to further unnecessary testing. There is also the loss of the patient’s time in going to have the test and jumping through related biometric screening hoops.

Additionally, I’m not aware of a significant amount of high-quality research that shows that these programs actually work as far as driving healthy behavior or reducing overall healthcare expenditures. There are a handful of papers but the design and execution are somewhat variable. I’m not sure how I feel about employees being part of an experiment – when I was in academics, I would have to get approval from the Institutional Review Board to do something like that with my staff. Employers, however, have carte blanche to do whatever they want.

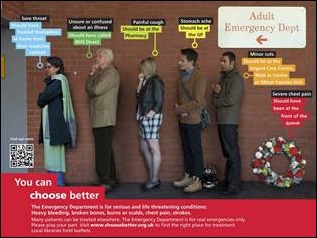

Everyone is awfully keen on these “wellness” programs, but they’re of varying quality. I saw a patient at the office last week who just needed documentation that he had a “physical” so he can get a discount on his insurance. There was no description of what exactly was to be included in the physical. The general “physical” has not been shown to reduce morbidity or mortality. Age-appropriate preventive and wellness visits can have an impact, but they’re best performed by a primary care physician who knows the patient and his or her history.

Unfortunately he showed up at our urgent care, where in the absence of specific criteria (such as pre-participation sports physical or a pre-employment physical), the content can be somewhat variable. Half our physicians are Emergency Medicine certified and they’re not that into continuity of care. He also presented to the office the day after Thanksgiving, which is historically one of the top three busiest days of the year at our practice and probably not the best choice for a preventive medicine visit unless you want to catch influenza or an upper respiratory infection in the waiting room.

I picked him up rather than one of the ED docs, so he did receive a full age-appropriate preventive medicine visit with preventive health counseling and notes on what screenings he should start having and when. I’m not sure how much he actually absorbed, though, and since we’re a walk-in urgent care, there’s not likely to be much continuity.

Another spin on this is the employer-owned health practice, where employees actually see on-site physicians for wellness visits, chronic disease management, and associated services. A friend of mine started working in one of these practices last year and found it to be much harder than she anticipated. She finds a tremendous conflict of interest with patients tending to want to conceal certain information that they wouldn’t want their employers to know. Although there are supposed to be safeguards in place, patients don’t always trust them.

Another negative aspect of open enrollment is the annual churn of patients having to change physicians when their coverage changes. Often this means starting over in the middle of treatment or having delays in care due to the need to obtain new referrals and authorizations. When I was in a traditional primary care practice, January always brought a flood of requests to transfer medical records, often with notes from the patient apologizing for leaving and asking us to let them know if we ever decide to start taking XYZ insurance plan.

For someone who became a family physician because I hoped to care for people longer than a year or two at a time, it was just sad. I’m personally averaging five primary care physicians in the last 15 years, which isn’t ideal as a patient.

I’m not sure what the answer is, but I hope it involves the ability of patients to choose physicians based on quality and cost and without network restrictions or burdensome processes. Somehow I think that’s just too much to ask, though.

What do you think the answer might be? Email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Beginning my comments by conessing that I too have been part of the problem, but it seems that much of…