Top News

Private equity firm New Mountain Capital will combine three of its healthcare billing portfolio businesses into a new company that is valued at $3 billion.

The companies are Rawlings Group, Apixio’s payment integrity business, and Varis.

Datavant has acquired Apixio’s Connected Care platform and value-based care solutions as part of the transaction.

The CEO of the unnamed company will be David Pierre, formerly COO of CVS Health-acquired Signify Health.

Reader Comments

From ID Protector: “Re: Optery. The CEO mentioned on their website is me, and the friend that introduced me to Optery was you, from an HIStalk post.” Pretty cool. Optery is a service that gets your name and personal information (address, phone number, age, family members, etc.) removed from websites that are easily found by Googling. Sign up for a free Optery account to see where your information is available for the world to see. I mentioned my personal experience with it in October 2021. I’ve been paying $3.99 per month for basic removal, but because of this CEO’s memory jog, I just now upgraded to Optery Extended for $120 paid annually after applying a promo code that I found online. His example was shocking – someone used his online information to obtain a fake driver license and apply for $50 million in PPP loans, not to mention that the personal information of employees makes it easier for hackers to breach a company. I just now chose a high-profile, Optery-free executive, and within 60 seconds, had photos of their house, what they paid for it, the names and ages of their family members, and details about their spouse’s employer.

Webinars

September 10 (Tuesday) noon ET. “Overcoming Hurdles in Specialty Med Access Under Medical Benefits.” Sponsor: DrFirst. Presenters: Drew Hunsinger, VP of corporate business development, DrFirst; Tyler Wince, MEd, VP of product and technology specialty solutions, DrFirst. More specialty medications, which made up 80% of FDA’s new drug approvals last year, are falling under medical benefits, which challenges the patient care processes and efficiency of providers. Medication access experts will discuss how automation and unified medication management solutions can ensure better outcomes for patients and providers by addressing patient access hurdles and enhancing the ‘stickiness’ of EHRs. They will also provide insights into how regulatory changes such as interoperability and prior authorization mandates will affect healthcare stakeholders.

September 17 (Thursday) noon ET. “Level Up Your Stars – Innovative Approaches to Boosting Quality Performance.” Sponsor: Navina. Presenters: Dana McCalley, MBA, VP of value-based care, Navina; Michael S. Barr, MD, MBA, chief medical officer, PreferCare; Yair Lewis, MD, PhD, chief medical officer, Navina. The presenters will explore strategies to boost quality performance and close care gaps effectively. Topics include enhancing quality metrics, developing strategies for care gap closure, leveraging AI for enhanced performance, and optimizing workflows.

September 19 (Thursday) 1 ET. “Cuttng-Edge Conversations: A Fireside Chat With Top CMIOs.” Sponsor: DrFirst. Presenters: Drex DeFord, MSHI, MPA, This Week Health; Lacy Knight, MD, MSMI, Piedmont Health; Jake Lancaster, MD, MSHA, MS, Baptist Memorial Health Care; Colin Banas, MD, MSHA, chief medical officer DrFirst. This fireside chat will distill key points from 15 CMIO participants of the 229 Executive Summit. Topics include the impact of AI on clinical workflows, strategies for optimizing healthcare operations, addressing physician burnout and patient safety, and advances in population health management.

October 3 (Thursday) 1 ET. “Navigating AI-Powered Medical Interpretation: Insights for Health Leaders.” Sponsor: Globo. Presenter: Dipak Patel, CEO, Globo. AI is redefining how providers can communicate with patients who speak limited English. However, not all LLMs are created equal, and their potential and limitations need to be examined further. Globo has published its results from testing several LLMs. This webinar will address the promises and perils of AI-enabled medical interpretation in summarizing that research in four key domains: the process of AI interpretation, how to measure it, the state of AI tools today, and the areas where AI falls short with interpretation.

Previous webinars are on our YouTube channel. Contact Lorre to present or promote your own.

Acquisitions, Funding, Business, and Stock

Netsmart acquires post-acute market intelligence firm HealthPivots, which it will integrate with CareFabric to support the transition to value-based care.

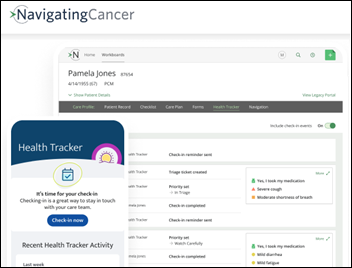

National oncology practice operator OneOncology acquires Navigating Cancer, which offers a patient engagement and care management platform.

Business Insider profiles Commure as “the weirdest startup in healthcare,” having raised $1 billion at a $6 billion valuation but then walking away from its original mission of developing a healthcare data integration platform to instead offer efficiency-boosting automation for healthcare administrative tasks. The company’s acquisitions include Augmedix, PatientKeeper, Strongline, and Rx.Health. Insiders say that the October 2023 “merger” of Commure and Athelas was actually a Commure acquisition, with products from Athelas becoming Commure’s primary growth engine. Athelas CEO Tanay Tandon took over as Commure’s fourth CEO in October 2023.

Sales

- In Canada, Nova Scotia Health will implement conversational web visitor search tools, EHR search, and radiology workflow from Google Cloud in a five-year, $31 million project.

- Sentara Home Care Services goes live on WellSky CareInsights and Value-Based Insights, integrated with their EHR.

People

City of Hope hires Simon Nazarian, MBA (Optum) as EVP/chief digital and technology officer.

Michael Justice, MBA (Medical Advantage) joins Mind 24-7 as SVP of technology.

University of Chicago Medicine promotes Karen Habercross, MBA, MSW to VP/chief information security and privacy officer.

Industry long-timer Laura Anderson (Elsevier) joins IKS Health as chief product officer.

EHR vendor Canvas Medical promotes Adam Farren, MBA to CEO. He replaces founder Andrew Hines, who will transition to CTO.

Erik Johnson (BioMérieux) joins Harmony Healthcare IT as VP of marketing.

NVoq hires Dawn Iddings (Netsmart) as chief revenue officer.

Hugh Brennnan (11TEN Innovation Partners) joins Cordea Consulting as EVP of sales.

Greenway Health hires Geordie Sanborn (Arvest Bank) and Chuck Rackley (Infinx) as sales VPs.

Announcements and Implementations

University of Iowa Health Care rolls out Nabla’s ambient technology to all of its clinical workforce, including faculty, advanced practice providers, allied health professionals, trainees, and students. UI Health Care will work with Nabla to develop new use cases and improve its Epic integration.

IRhythm, which offers an ambulatory cardiac monitoring system, signs an exclusive license to incorporate BioIntelliSense’s technologies that measure pulse oximetry, accelerometry, and trending non-invasive blood pressure.

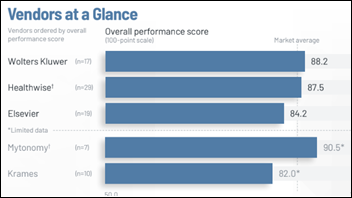

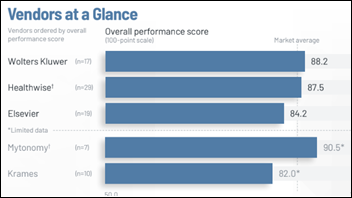

A new KLAS report on patient education solutions notes that 2024 Best in KLAS winner Healthwise, which was acquired by WebMD this year, is used by the widest variety of organizations. Wolters Kluwer is strong in EHR and portal integration, while Elsevier shines with its patient-friendly content. New vendor Mytonomy publishes short-form videos.

Government and Politics

The Republican National Committee alleges to election officials in six states that Vot-ER may be violating election laws, stating that the organization’s goal is to turn “every check-up and doctor’s visit into a political lecture” by pressuring patients to vote in a certain way as a condition of receiving medical care. Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX) previously asked Epic to respond to his concerns that its users could be registering non-citizen voters in Vot-ER. Vot-ER Executive Director Aliya Bhatia, MPP provided this response:

Vot-ER is proud of empowering health professionals and patients to vote, many of whom face significant barriers to civic participation. It’s unfortunate and frankly a shame that our nonpartisan efforts to promote civic engagement are coming under unwarranted scrutiny. Vot-ER has always been clear in its mission to remain nonpartisan, and we are guided by a bipartisan advisory board, including Republican and Democratic former elections officials, to ensure that our work reflects the needs and concerns of all voters, regardless of political affiliation. Vot-ER does not promote or endorse any political party or candidate, participation is entirely voluntary, and nothing in our programming remotely suggests that patients are pressured or coerced to register to vote. Moreover, we have protocols and technology in place to prevent ineligible individuals from registering, and any suggestion otherwise is simply false.

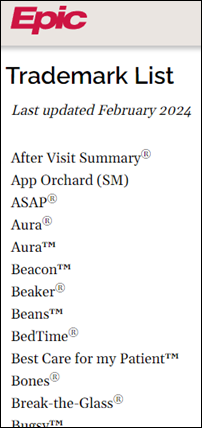

I mentioned the Epic app name post from interoperability guy Brendan Keeler earlier this week, so here’s another fun thread in which he looks at some of the interesting comments that ASTP received about HTI-2. He cites an anonymous commenter who was “coming out guns blazing” with these points (not Brendan’s):

- Questionable applications have already joined the network by exploiting its lenient onboarding process, which could include using fake NPIs and websites.

- Ineffective monitoring allows organizations to siphon off data without sharing data of their own.

- ASTP should follow Carequality’s focus on thorough vetting and continuous monitoring, which could include real-time participant monitoring and removal and notifying practices when their credentials are used.

Other

Kaiser Permanente hematologist / oncologist Faisal Cheema, MD says that he’s happy that they are using Abridge for ambient documentation after piloting Nabla Copilot. He says that Copilot was effective but not integrated with Epic (he didn’t say whether it was an app problem or KP decision) and Abridge’s integration with Epic Haiku was a game-changer. Next, he would like to see transcription of virtual visits directly from the smartphone app.

Hamilton Health Sciences profiles cardiologist Darryl Leong, MBBS, MPH, MBiostat, PhD, who is also associate CMIO for research, and his involvement with the organization’s use of Epic in research.

Sponsor Updates

- Middletown Medical (NY) sees reduced claim rejections, decreased claims submission lag, and ROI savings after adding RCM capabilities to its EClinicalWorks EHR.

- Black Book’s latest survey of VC and PE healthcare leaders reveals priorities for healthcare IT investments in 2025.

- CereCore will present at Meditech Live September 27 in Foxborough, MA.

- Arcadia publishes a new report, “The healthcare CIO’s role in the age of AI.”

- Artera publishes a new customer snapshot featuring Newton Clinic.

- Availity partners with Iodine Software to bring advanced mid-revenue cycle solutions to its Availity Essentials Pro customers.

- AvaSure will host the 2024 AvaSure Symposium October 2-4 in Grand Rapids, MI.

- Capital Rx releases a new episode of The Astonishing Healthcare Podcast, “Never Move Again, a Paradigm Shift in Pharmacy Benefits, with AJ Loiacono.”

- The American Health Law Association features Clearwater Chief Risk Officer and Head of Consulting Services and Client Success Jon Moore on its latest podcast.

- Memphis VA Medical Center (TN) expands its use of CliniComp solutions.

- CloudWave publishes a new case study, “Safeguarding Patient Care: Emanate Health Adopts OpSus Live for Enhanced EHR Security.”

- Crossings Healthcare Solutions, FinThrive, and Nordic will sponsor Oracle CloudWorld 2024 September 9-12 in Las Vegas.

- Ellkay will exhibit at Mayo Clinic’s Leveraging the Laboratory Conference September 17-18 in Rochester, MN.

- Elsevier offers free access to research and clinical resources via its Mpox Information Center to accelerate the fight against viral disease.

- FinThrive releases a new episode of its Healthcare Rethink Podcast, “Is the Boom of Digital Health Really Booming?”

- Five9 will present at SaaStr Annual 2024 September 10 in San Francisco.

Blog Posts

Contacts

Mr. H, Lorre, Jenn, Dr. Jayne.

Get HIStalk updates.

Send news or rumors.

Contact us.

Thank you for the mention, Dr. Jayne — we appreciate the callout, the kind words and learning more about the…