Top News

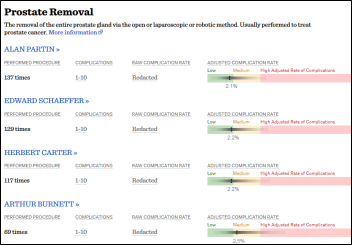

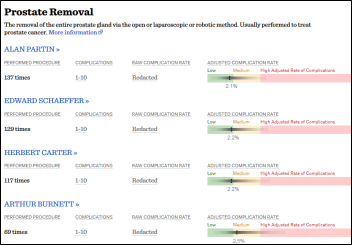

ProPublica publishes its Surgeon Scorecard of Medicare complication rates for eight elective procedures. It suggests that choosing the right surgeon is more important than choosing the right hospital, adding that hospitals are lax in monitoring surgeon performance. Low-performing surgeons gave the expected counter-arguments: (a) using only Medicare data is not statistically valid; (b) readmissions don’t necessarily indicate complications; (c) Medicare gets a lot of incorrect and therefore unreliable information from providers; and (d) doctors who take on high-risk patients or treat patients aggressively are overly penalized.

However, a surgeon with one of the lowest complication rates in the country – who had to shut down his practice because producing better results required too much of his time to make a living – concludes, “My results were very good. Other orthopedists in the Twin Cities had horse shit results and made more money. The general public never knew what the results were.”

Reader Comments

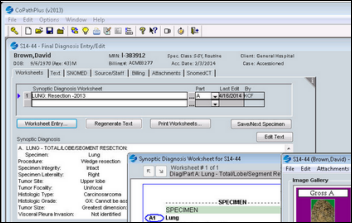

From Gene Gene: “Re: CoPath. Sunquest sells CoPath and PowerPath, each created outside of Sunquest and each with its own build and guts. Cerner also sells two anatomic pathology systems, CoPathPlus and a product called Millennium that they had before swallowing CoPath from DHTI. Both are sold and supported today.”

From DrLyle: “Re: startup advice. I saw your comments, and by weird coincidence, I had posted my thoughts early on the same topic (after reading yet another blog post earlier).” DrLyle’s “Advice to Healthcare Startups” is a succinct, meaty list that includes strong endorsement of Lean Startup methods, which intrigued me enough that I bought the Kindle version of the book describing them. I’ll report back if it looks interesting.

From Sonny Bunz: “Re: HIStalk sponsors. You list the new and renewing ones, and in the interest of transparency, you should also list those who do not renew their annual sponsorship. People should know if their vendor is not continuing their participation for whatever reason and it would be nice to thank them for their previous support.” I’m somewhat uncomfortable with this since I’m not sure the average reader should even care, but the non-anonymous reader (someone you would likely know) convinced me in a telephone call that it would be a nice gesture to say goodbye to companies that have supported me while also being fully transparent about who is sponsoring. Priorities and budgets change, companies refocus or get acquired, my primary contact moves on and we get handed off to a marketing associate who has never heard of HIStalk, or they’re unhappy that I wrote something negative or declined to fawn over a fluffy press release – it happens. Regardless, I appreciate their support, especially those who had sponsored for several years. These go back to the beginning of 2015.

3M

AT&T

AtHoc

CommVault

Connance

Cornerstone Advisors

Deloitte

DocuSign

EnovateIT

Harris Corporation

Infor

Intelligent InSites

Juniper Networks

Levi, Ray & Shoup

Lincor

Logicworks

McKesson

MedAssets

Medfusion

MediQuant

NextGen

Optum

Predixion

Quantros

RelayHealth

SCI Solutions

ScImage

Sentry Data Systems

Shareable Ink

SRSsoft

Symantec Healthcare

TrainingWheel Learning Solutions

Truven Health Analytics

From Blue Coupe: “Re: Anthem breach. I got a letter today that it doesn’t involve only Anthem plan holders, but also people who worked at companies who contracted with Anthem even if that person didn’t choose Anthem’s coverage.” I don’t know why companies would give Anthem the records of employees who didn’t buy its insurance, but I suspect it will get those companies and maybe justifiably so.

From Capisco: “Re: PHR use agreements. MedStar’s says the user is responsible if malware uses my credentials to get into their system. I would have to trust their forensics that blamed the breach on me since I couldn’t validate that. It also says the patient is responsible for all attorney fees. The agreement doesn’t list a MedStar contact for questions and the folks I reached there don’t seem to know or care.”

From Banished from Topeka: “Re: readmissions. Humana’s chief medical officer said in a conference this morning that the most relevant predictor of a hip replacement readmission for an older woman is whether she has food in the refrigerator.” I don’t doubt it a bit – the more we try to understand and manage healthcare costs, the more we have to delve into how social services are delivered as well since the two can’t be separated. Poor nutrition, loneliness, sanitation problems, physical inactivity, educational deficiencies, and lack of reproductive knowledge are all health problems that eventually cause an immense expense, but don’t get much attention or funding in this country for a variety of reasons. Health systems who go at risk will have no choice but to get off their high horse and coordinate with social services agencies.

From Captain Phasma: “Re: Sheltering Arms Rehab Hospital. Looks like they’ve gone with Cerner. Curious who competed.” The announcement doesn’t say.

From HITrainer: “Re: Glens Falls Hospital, NY. Heard from someone who works there that they are uninstalling Epic, which would be a first for Epic. Can you verify? This would be huge.” Unverified since I couldn’t locate an email address for CIO John Kelleher, but maybe someone will step up.

HIStalk Announcements and Requests

It’s hard to believe that the HIMSS conference is just seven months away. We are already planning HIStalkapalooza and have signed contracts for the facility and band. Companies interested in sponsoring can contact Lorre, which would be comforting to me since I’m on a very large financial hook in providing a free party for close to 1,000 people. We have several levels of sponsorship available, but I’ve dubbed the biggest one “Rock Star CEO,” which includes:

- 100 invitations.

- A private lounge (capacity 100) with its own bar and food plus two VIP boxes for entertaining prospects, partners, and company executives.

- The company CEO introduces the band, gets four all-access passes, and enjoys a meet-and-greet with the band back stage after their performance.

- An on-stage banner.

- Special recognition from the stage.

Webinars

July 14 (Tuesday) noon ET. “What Health Care Can Learn from Silicon Valley.” Sponsored by Athenahealth. Presenter: Ed Park, EVP/COO, Athenahealth. Ed will discuss how an open business structure and strong customer focus have helped fuel success among the most prominent tech companies and what health care can learn from their strategies.

July 22 (Wednesday) 1:00 ET. “Achieve Your Quality Objectives Before 2018.” Sponsored by CitiusTech. Presenters: Jeffrey Springer, VP of product management, CitiusTech; Dennis Swarup, VP of corporate development, CitiusTech. The presenters will address best practices for building and managing CQMs and reports, especially as their complexity increases over time. They will also cover quality improvement initiatives that can help healthcare systems simplify their journey to value-based care. The webinar will conclude with an overview of how CitiusTech’s hosted BI-Clinical analytics platform, which supports over 600 regulatory and disease-specific CQMs, supports clients in their CQM strategies.

July 29 (Wednesday) 11:30 ET. “Earning Medicare’s New Chronic Care Management Payments: Five Steps to Take Now.” Sponsored by West Healthcare Practice. Presenters: Robert J. Dudzinski, PharmD, EVP, West Healthcare Practice; Colin Roberts, senior director of healthcare product integration, West Healthcare Practice. Medicare’s new monthly payments for Chronic Care Management (CCM) can improve not only patient outcomes and satisfaction, but provider financial viability and competitiveness as well. Attendees will learn how to estimate their potential CCM revenue, how to use technology and clinical resources to scale up CCM to reach more patients, and how to start delivering CCM benefits to patients and providers by taking five specific steps. Don’t be caught on the sidelines as others put their CCM programs in place.

July 30 (Thursday) 3:00 ET. “De-Silo Your Disparate IT Systems Around the Patient with VNA.” Sponsored by Lexmark. Presenters: Steven W. Campbell, manager of diagnostic applications and interfaces, Piedmont Healthcare; Larry Sitka, VNA evangelist, Lexmark. The entire patient record, including both DICOM and non-DICOM data, should be available at the point of need. Disparate, aging systems that hide data inside departmental silos won’t cut it, nor will IT systems that can’t integrate medical images meaningfully. Learn how Piedmont Healthcare used a vendor-neutral archive to quickly and easily migrate its images and refocus its systems around its patients.

Previous webinars are on the YouTube channel. Contact Lorre for webinar services including discounts for signing up by July 31.

Acquisitions, Funding, Business, and Stock

Nineteen-employee, Seattle-based Arivale, which will offer genetic analysis and coaching, raises $36 million. The company’s co-founder and CEO says that its personal coaches are “our secret sauce. They take this very complex data set with the support of a physician and scientists, come up with three or four actionable recommendations, and then help you succeed in achieving those recommendations.”

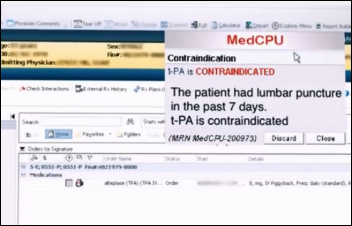

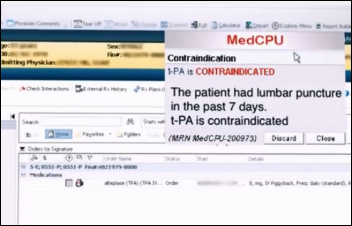

MedCPU raises $8 million in funding to expand its clinical decision support business.

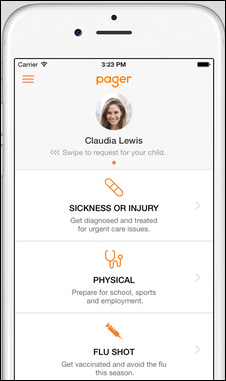

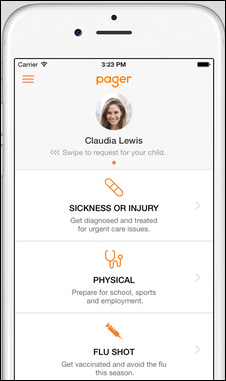

New York-based doctor house call provider Pager, founded in 2014 by Uber’s CTO, raises $14 million and announces plans to expand to San Francisco. The company, which has 40 doctors, has added insurance acceptance and EHR data sharing. One of the investors says connecting to the EHRs of health systems will be hard, but he’s encouraged that some of those organizations are willing to work with the company.

The Teamsters try again to convince McKesson shareholders to limit executive payouts that would be triggered by a change in control, a proposal that earned 44 percent approval at last year’s annual meeting. Five McKesson executives would automatically collect $283 million if the company changes hands, $142 million of that due CEO John Hammergren alone.

Medtronic will acquire RF Surgical Systems, which offers RF-powered surgical sponge counting, for $235 million.

In New Jersey, Barnabas Health and Robert Wood Johnson Health System will merge to create RWJ Barnabas Health, the state’s largest health system with $4.5 billion in revenue and 30,000 employees.

Sales

Piedmont Healthcare (GA) chooses Health Catalyst’s data warehouse and analytics.

The Indiana HIE selects Clinical Architecture’s Symedical terminology management software suite for interoperability.

Express Medical Billing will implement CompuGroup Medical US’s CGM DAQbilling practice management solution.

People

Ivo Nelson (Next Wave Health) joins the board of revenue cycle vendor Global Healthcare Alliance.

Announcements and Implementations

The cancer center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (NH) goes live on RTLS patient status tracking from Versus Technology.

Mike “PACSMan” Cannavo, whose occasional HIStalk service has included writing guest articles and manning my HIMSS booth, is offering PACS arbitration services and PACS replacement cost assessment.

Sunquest Information Systems will partner with TriCore Reference Laboratories to develop diagnostic laboratory software to support population health, precision health, and integration pathology.

PerfectServe announces that its unified clinical communications and collaboration system reaches 50,000 physician users, a 51 percent increase in 18 months.

Adena Health System (OH) will go live August 1 on its $15 million Meditech 6.15 conversion.

Government and Politics

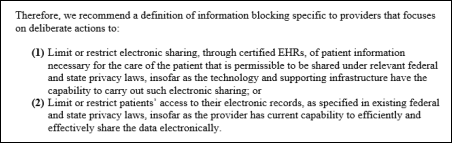

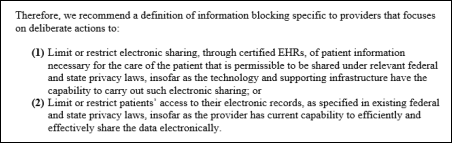

The American Hospital Association objects to the information blocking provisions of the 21 Century Cures Act that was just approved by the House and has moved on to the Senate, saying its definition is too broad and the OIG has an incentive to levy fines since it gets to keep the money (that’s an interesting conclusion). AHA says the government should make EHR vendors prove that their products don’t block information sharing, while providers should be required to share patient information only if they are capable of doing so. AHA specifically says providers should not be held liable for information blocking because of technical limitations or “high costs or fees imposed by certified EHR technology vendors for such electronic sharing or access,” or in other words, provider inconvenience is a valid excuse. AHA also objects to the bill’s elimination of the Health IT Standards Committee.

In India, the state of Haryana will connect 75 hospitals and three medical colleges via a statewide network, also announcing plans to issue a unique patient identifier to allow accurate record sharing.

Privacy and Security

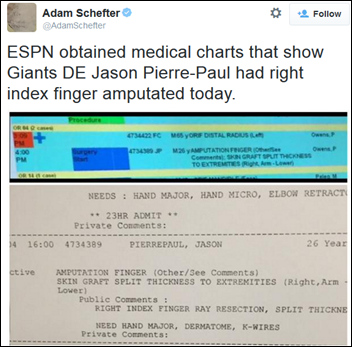

The ESPN reporter who tweeted a photo of an NFL player’s medical record says he could have done more (he didn’t explain what “more” means) due to the sensitivity of the situation, adding, “It didn’t look to me as if there was anything else in there that could be considered sensitive. NFL reporters report on all kinds of medical information on a daily basis. That’s part of the job. The only difference here was that there was a photo.” The reporter says the photo (which also included the information of a second patient) was sent to him unsolicited, which may mean it came from someone who knows the reporter rather than from a hospital employee, which Jackson Memorial Hospital is desperately hoping is true. The reporter also said that his high journalistic standards required the “ultimate supporting proof,” a claim that NBC Sports brilliantly dismisses as, “The ‘ultimate supporting proof’ wouldn’t have been a medical record containing sensitive and private information about Pierre-Paul and another patient, but the fact that Pierre-Paul eventually would have been seen in public with four fingers on his right hand.”

Innovation and Research

NIH awards a $3.1 million grant to Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota and HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research to developed web-based clinical decision support system for assessing acute abdominal pain in children, hoping to improve the diagnosis of acute appendicitis without the use of CT scans. A pilot study reduced CT usage by 25 percent.

A study finds that the caregivers want access to the medical information of their elderly patients to make it easier for them to coordinate care, but the patients themselves don’t want to give unlimited access because they don’t want to worry their loved ones or give up control.

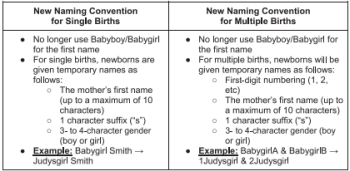

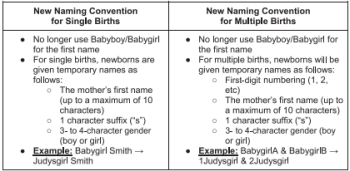

A study finds that hospital placeholders for unnamed newborns (such as Babygirl Smith) cause wrong-patient ordering errors, suggesting as an alternative using the mother’s first name in the form of Judysgirl Smith, which reduced errors by 36 percent.

Technology

A Washington Post article says it’s obvious that OR personnel shouldn’t be checking Facebook or email during a case, but adds that most hospitals don’t prohibit smartphone use during surgery since that would preclude the use of clinical apps as well.

A Delaware newspaper profiles the use of iPad-powered telemedicine in the Nemours Care Connect program, in which doctors in 40 regional EDs can collaborate via video with Nemours specialists. Nemours is also testing Google Glass for live streaming video from critical care transport nurses back to the hospital, although they’ve struggled with reliability and say that patients “look at me like I have three heads.”

Other

In Australia, SA Health is investigating the deletion of a radiologist’s comments from a patient’s electronic medical record. An ED doctor ordered a CT scan that a radiologist argued was not needed. The radiologist later found that a non-clinician hospital executive had entered the computer system as a superuser and ordered the scan against the stern warnings of the radiology manager. The angry radiologist recorded a patient note that criticized the executive “who stuck her nose in” and criticized the imaging system whose rollout had caused a two-week imaging backlog, which he speculated may have caused the death of another patient. The radiologist later found that his comments had been deleted, which he calls “very dangerous and very sinister.”

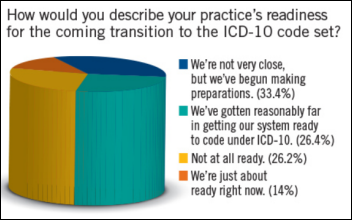

I don’t like surveys that don’t state their methodology, especially if the survey questions appear to be poorly designed, but I’ll pull out a few slightly interesting findings from this new Kareo-sponsored survey of physician practices.

- Two-thirds believe that EHR use improved patient documentation.

- Two-thirds say the EHR hasn’t paid for itself.

- One-third see fewer patients because of the EHR.

- Just over half of respondents are satisfied with their EHR vendor (although the question confused “vendor” and “product.”)

- Less than 10 percent will accept the Medicare penalty instead of trying to achieve Meaningful Use Stage 2.

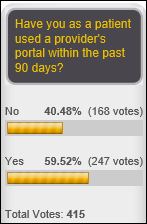

- Just over half offer a patient portal.

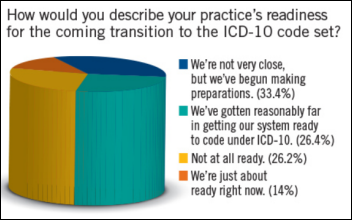

- Sixty percent say they aren’t ready for ICD-10, while 40 percent of respondents haven’t even asked their software vendors if they’ll be ready.

- Only 12 percent offer virtual visits.

KQED highlights the perinatal depression detection app of Ginger.io, which captures a baseline profile of user activity and notifies the provider of significant changes. It’s being piloted at Novant, Penn, and an unnamed California health system. The article’s headline says the app “harnesses big data” when that hardly seems the case, and while some experts say the app can help compensate for overly busy OB-GYNs who forget to ask about emotional status, the downside is that OB-GYNs might not participate and the patient might not feel comfortable disclosing the information.

TriHealth spent $9.5 million to implement Epic at its new affiliate, 45-bed McCullough-Hyde Memorial Hospital (OH), which went live in a July 1 conversion.

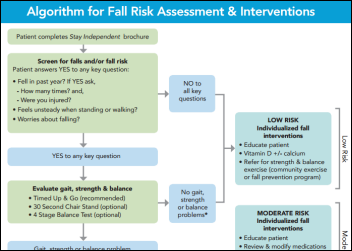

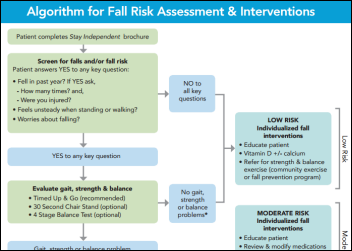

A White House fact sheet from its Conference on Aging notes that Epic will release a patient falls assessment tool based on CDC’s STEADI guidelines by the end of 2015.

Weird News Andy titles this “Smooth Operator.” A man walks into Morton Plant Hospital (FL), rolls a $48,000 surgery table to the loading dock in broad daylight, and hauls it off in his van. The suspect, who was captured on video and arrested, is a medical device technician with a few prior arrests.

Sponsor Updates

- HealthLoop posts “CMS is asking doctors to put a warranty on their services.”

- First Databank will participate in Athenahealth’s “More Disruption Please” hackathon July 24-26 in Austin, TX, providing attendees with access to its FDB Cloud Connector web API.

- Nuance joins Athenahealth’s “More Disruption Please” program, adding its Dragon Medical 360 to the Athenahealth Marketplace.

- ZeOmega Chief Strategy Officer Nandini Rangaswamy is named to the Dallas Business Journal’s “Who’s Who in Healthcare.”

- ADP Advanced MD offers “New ICD-10 transition period, a little breathing room.”

- Aventura will exhibit at the Healthcare Finance Institute July 26-28 in Chicago.

- Awarepoint announces updates to its awareAssets asset tracking and workflow optimization tool.

- Caradigm offers “Moving Healthcare Analytics from Measurement to Management.”

- PatientSafe Solutions posts “Achieving Mobile Care Orchestration: How One Hospital Uses Smartphones.”

- CareSync COO Amy Gleason offers “Remember the ME in Medicine” at the White House blog.

- CareTech Solutions will exhibit at the AHA and Health Forum Leadership Summit July 23-25 in Troy, MI.

- CompuGroup Medical will exhibit at the AACC 2015 Annual Meeting July 28-30 in Atlanta.

- Practice Unite offers “Changing Chronic Care Management Services Reimbursement.”

Sponsors on the 2015 HCI 100

Allscripts

Anthelio Healthcare Solutions

Beacon Partners/KPMG

Burwood Group

Capsule Tech

Caradigm

CareTech Solutions

CTG

EClinicalWorks

Elsevier

Encore Health Resources

Evolent Health

Experian/Passport Health

GE Healthcare

Greenway Health

Imprivata

InterSystems

Leidos Health

Lexmark Healthcare

Medecision

Medhost

Merge Healthcare

MModal

Navicure

Netsmart

Nordic

NTT Data

Nuance

Orion Health

Premier

Sunquest Information Systems

Surgical Information Systems

T-System

TeleTracking Technologies

The Advisory Board Company

The HCI Group

The SSI Group

Verisk Analytics

Wolters Kluwer Health

Xerox

ZirMed

Zynx Health

Contacts

Mr. H, Lorre, Jennifer, Dr. Jayne, Dr. Gregg, Lt. Dan.

More news: HIStalk Practice, HIStalk Connect.

Get HIStalk updates.

Contact us online.

I initially questioned the profile's authenticity because all of the headshots in the profile are clearly generated or enhanced by…