Daniel Stein, MD, PhD is director of informatics and innovation at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, NY.

Tell me about yourself and your work.

I call myself a clinical informatician. I went to med school and then completed a PhD in informatics at Columbia. I’ve been on the informatics faculty at a few institutions. I started at Columbia and then moved over to Cornell, both of which are part of New York Presbyterian Hospital.

I was recruited to Memorial Sloan Kettering about a year and a half ago by a mentor of mine from when I was at Columbia who is now MSK’s Chief Health Informatics Officer, Pete Stetson, MD. I work for Pete as a director in health informatics, focusing on innovation.

My first assignment was to help stand up and launch a new surgical platform here at MSK, which is called the Josie Robertson Surgery Center. That is an ambulatory, freestanding surgical facility for oncology cancer procedures.

Even though I was happy where I was before, Pete knew that I wouldn’t be able to turn it down. It’s quite rare in New York City to start fresh. This was a brand new facility. It was being designed from the ground up as an innovation center, to be chock full of technology and trying to use health IT and informatics to enable this place to do surgeries in a way that they’re not being done anywhere else.

I couldn’t turn that down. To me, it’s my version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – except in this case, the chocolate factory is a high-tech surgery center, and I’m just thrilled to be contributing as an informatician to the superb care we’re delivering.

The director of the Josie Robertson Surgical Center is anesthesiologist Brett Simon, MD, PhD. Much of the design and the success of the center is due to his visionary leadership.

What your readers may find most interesting about this surgery center is that one main goal is to do oncology surgeries in an ambulatory setting that aren’t typically done as outpatient procedures. The technology we have there plays a big role in enabling that in a manner that maintains the high quality and safety standard that we have established here at MSK.

The way we got there was that for several years before opening the surgery center, we developed a program that we call the Ambulatory Extended Recovery program, or AXR, in our surgery department. We were doing cases as if they were being done in the Ambulatory Center, but we did them in our main hospital. If for some reason the patient couldn’t go home, that would be OK.

For a few years, we learned how to figure out — through analytics and through certain patient factors, in terms of co-morbidities and other risk factors — what good candidate cases would be to do in an ambulatory setting. When it was time to open the center, which was a year ago this past January, we would know which patients we could do in this setting and which patients we couldn’t.

We have five surgical services in the center — breast, head and neck, gynecology, plastic and reconstructive, and urology. About a third of the cases that we do are AXR cases. Those are cases that typically — even here at MSK and certainly at other hospitals — wouldn’t be done with just one overnight stay, such as mastectomies with reconstruction, or minimally invasive robotic prostatectomies.

Because we took our time to figure out how to do this the right way before opening the center, and because of all of the informatics-enabled tools that we have put in place, we are seeing that not only are we doing these cases safely, we are getting overwhelmingly positive feedback from our patients. They like how smoothly the place runs and they like going home sooner rather than staying in the hospital.

We’ve looked very closely at key outcome measures over our first year and we’re seeing complication / transfer / admission rates that are even lower than we anticipated and lower than what we see reported in the literature for ambulatory surgical centers that do much simpler, non-cancer related procedures. .

What are some innovative ways IT systems are being used in the surgery center?

One of the important things we did before the center was opened was to develop procedure-specific pathways that these patients would be on. When we opened, we made changes globally throughout all of our information systems to support not only monitoring patients on these tailored pathways, but making progress on the pathways visible and apparent to all the people in the facility.

From the beginning of the surgical encounter, an order set is placed that puts the patient on the pathway in our EHR. That order set dictates everything that happens downstream from that. There are certain nursing documentation flowsheets that correspond to that order set that require documenting specific items that we monitor.

Then we have status boards that we’ve built in the EHR that show, for each patient who’s in the ambulatory surgical center, where they are on that pathway and whether they’re meeting criteria. Are they making good progress or is there something that requires attention on their specific pathway?

There’s discrete documentation that’s completed by the nurses. That documentation is rolled up into a green or red cell on a table in a status board right in the EHR. We can monitor all the patients who are in the facility in real time and determine whether they’re meeting the requirements that they need to have a safe discharge by the next day.

There are three major categories of items that we monitor in those status boards. Number one is what we call the patient’s well-being. That consists of factors like their blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate, then other things like their nausea and vomiting. We take the structured documentation in those areas and roll it up to determine if they are meeting criteria for well-being. If not, we look into what’s going on and see if we can get them back on track.

We have some pathway-specific educational milestones that we have to meet depending on the surgery. For example, if the patient is a prostatectomy patient, we make sure they receive certain education around management of their Foley catheter before they go home.

Finally, we’re monitoring their activity status. We look at a combination of two things. Their ambulation — are they getting up out of bed and moving around? — and their PO intake – are they able to keep food and drink down?

We have some interesting technology that we’re leveraging for their ambulation. We have a real-time location system in the facility. RTLS is used a lot in industries outside of healthcare for things like asset tracking, to help you know where things are moving around in a facility. It’s being used more and more in healthcare. I think we’re one of the earliest, if not the first place, to try to integrate RTLS so deeply into the workflow of clinicians in a setting like this.

Everybody who is in the surgical facility wears a badge. These badges can be used to locate clinicians. They can be used to locate patients. We even give a badge to a caregiver or family member who might come with the patient so that we can let them stay where they are comfortable and we can approach them without having to call out the patient’s name in a waiting area. There’s a whole lot of things we do with RTLS that improve the patient and family experience, improve the awareness of the care team members, where people are. It’s like the Marauder’s Map in Harry Potter. You can see where everybody is in real time and see who’s in what room.

We use that for a variety of things. We have a lot of patient- and family-facing applications. When you’re in the hospital, a lot of people are coming in and out of the room. Sometimes it’s hard to keep track of who’s who, especially if you’re a little disoriented or if you’re on pain medications. One of the nice patient-facing applications of RTLS is that when you walk into one of our rooms, there’s a TV on the wall and up on the TV will pop the name of the clinician and their role. That gives people a clue of who’s walking into the room. It’s nice to give that to the patients, as so many different members of the team come in and out so frequently.

Because we are monitoring the progress of the patients through their pathway and we know when they’re in the OR and when they’re in the recovery room, we surface that information directly to the family members or caregivers down on the floor where they’re waiting. We have a big status board with a coded identifier. We can show them, now your husband is in the pre-op area, now he’s in the operating room, now he’s in the recovery room, now he’s ready for visitors. That board updates in real time. People find it very useful — they’re not just wondering what’s happening and what’s going on.

Since patients are wearing those badges, we’re using RTLS to estimate their steps they’re taking, almost like a Fitbit, and trying to work that into our clinical assessment of how they’re doing with ambulation.

We have RTLS integrated with our nurse call system and our telemetry units. If there’s an alarm that goes off in a patient’s room, the moment that one of the clinicians walks in, it will silence the alarm so they can focus on the patient and turn that off. Some neat integration there.

We’re exploring some telemedicine / telepresence. We’re facilitating discussion between some of our surgeons and the patients through videoconferencing and also exploring the use of a telepresence robot.

We have a secure text messaging platform being rolled out across the organization. We’re using it at the surgery center so that our clinicians can use text messaging as a communication modality while ensuring patient privacy. We’re tying that into other systems to try to automate text messages based on people’s roles. For example, a nurse can text the generic role “hospitalist on call” and that role will map to the individual who happens to be on call that night.

I would assume that for oncology in general and for your surgery center specifically that you must use patient engagement technology to keep a connection with the patient and family not just for that surgery, but throughout their oncology journey.

I’m glad you asked. We have a lot to talk about on that.

Of course, we have our traditional patient portal. We’re one of those organizations that has a lot of different systems just from our history. We even have two major EHRs in play, especially for surgical patients. We have a homegrown portal system that we call MyMSK. It ties it all together for the patients.

Even before they get here, we have tailored educational materials that are sent in an automated way. When the surgery is scheduled at Josie Robertson, patients will get notified through the portal that they’re having their surgery there. It gives them some basic information about where they’re going, what the facility is like, and what kind of things are there. It also gives them tailored educational material to their procedures.

We have a patient-engagement module as part of our portal we call MSK Engage. Someone might say it’s kind of like we built our own SurveyMonkey or survey platform. We specifically didn’t call it a survey platform or survey tool because we consider it a patient engagement tool. There’s a lot more to it than just delivering surveys to the patients.

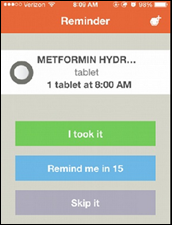

We are delivering assessments to our post-operative patients and trying to capture their post-operative symptoms. We’re doing some daily symptom scoring with a pilot group of patients that are coming in through this surgical center. We’ve built a whole set of tools around that platform that monitors for results or responses that might be out of range.

There’s some interesting challenges that are posed when you do that. You have to figure out what to do when you detect something that might be worrisome or out of range. Things that might seem trivial, like figuring out who the appropriate member of the care team is to notify, is really not that trivial to automate.

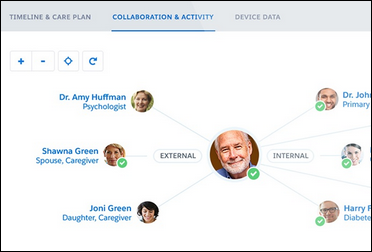

Systems have a lot of different people who touch a given patient’s chart. We’ve done a lot of work on building what is now rudimentary system that we hope in the long run will become a sophisticated care team engine and notification platform so that we can, for a given patient, have a good representation of who the members of the care team are, who would need be notified if we think a patient isn’t doing all that well, and how we would get in touch with them. We’re trying to build those pieces into our patient engagement platform. We’ve got pieces of that in place now.

We recently were awarded a PCORI grant specifically for a project that we’re doing at this surgical center involving collecting daily assessments for patients post-operatively that will be starting next month. The actual work for the grant is not only about collecting how the patients are doing post-operatively, but providing them with some normative data. This way they can see how they’re doing in relation to how patients like them typically are doing on post-op Day 1, post-op Day 2, etc. until they come back for their office visit. The principal investigator of the grant is Andrea Pusic, MD, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon who developed the BREAST-Q satisfaction and quality of life assessment for breast reconstruction patients.

We’re excited about this work because we think that a lot of the anxiety and a lot of the utilization — whether it’s phone calls to the practices or visits to our urgent care center — could be ameliorated just by knowing that at this point, on Day 3, it’s normal to be feeling a certain amount of discomfort or to have a certain set of symptoms or conditions. Maybe after a certain period of time, now you’re out of that normal range, so you should give us a call or you should start to get concerned.

The grant is about the impact of sharing that normative data with the patients and seeing if we can reduce anxiety around post-operative symptoms and pain management and reduce unnecessary utilization. This is a perfect center to be exploring these types of questions.

IBM Watson for Oncology was trained at your hospital and oncology seems to be on the cutting edge of using artificial intelligence and data aggregation for everything from imaging analysis to diagnosis, all the way through to literature searches and applied informatics at the point of care. What are the most interesting potential uses of technologies that you’ve seen that are impacting oncology practice?

You highlighted a lot of it. We have multiple groups focused on precision oncology and how we can sift through the treatments that we offer, the different conditions our patients have, and the way genomic data and the tumor markers and all these things affect the decision treatments. There are a number of groups at MSK that are working in those areas.

In surgery, which I can speak to the most, especially at a place like this, we’re starting with the basics. One thing we don’t do well enough is just taking the data that we have in our EHRs and from our visits and outcomes and surfacing it to the clinicians in a way that they can get instant feedback on how they’re doing and what’s going on.

A huge part of the informatics efforts around this surgical center is collecting the data that all these systems are generating — including RTLS, so we can see where people are and how they’re moving around — and feeding it back to our chief of surgery, the director of the center, and the clinicians themselves so that they can see how they’re doing. See what their outcomes are for their different groups of patients. Because we’re in this freestanding facility where there’s a strong commitment among clinicians, staff, and nursing to innovate, we can act on that data rather quickly.

I’ll give you an example of that. We created some dashboards that look at the duration of the stays of the patients after their surgeries. We have those advanced surgeries where we expect patients to stay at least overnight. However, a lot of the cases that we’re doing, maybe a simple lumpectomy for a patient with breast cancer, they’re not intended to stay overnight. They don’t need to stay overnight.

We created a simple dashboard that shows patients who are supposed to be real, true outpatients and indicates whether they stayed longer than anticipated or if they ended up having to stay overnight, which we can facilitate for one night at this center. Just by looking at that data, we were able to find a subpopulation of our patients who seemed to be more often staying longer than they should be. When we looked into it, we found it was mostly due to pain and pain control, which we’re tracking in our structured documentation that’s associated with the pathway that these patients are on.

Our anesthesiologists and our surgeons got together and had a good collaboration. They started a new method to increase the use of local anesthesia during the procedure so that the patient’s pain was managed better. Now we’ve reduced the extended stays for these outpatients by almost half in just several months.

You’re correct that there’s a ton of promise of using AI and machine learning and algorithms and genomic data to tailor care, especially in oncology. We still have so far to go just by looking at some more basic data and surfacing it in a way that’s understandable and allows you to recognize patterns that you may not have expected and then do some hypothesis testing and improving your processes and improving the quality of the care you’re delivering. I think the whole spectrum of data analytics has a ton of potential to improve the care we deliver.

Do you have any final thoughts?

It’s been very exciting for me since I came to MSK. We just came up on our anniversary of being open open at the Josie Robertson Surgery Center in January and we’ve learned a lot. We’ve got a lot more to learn. We’re trying to keep things innovative.

We performed about 6,500 cases in that first year. About a third of those were those AXR cases where we’re really cutting edge in terms of what we’re able to do and get people home and happy and safe and following up with the engagement platform. We’re excited that the PCORI grant gives us the opportunity to learn how to maximize that. We’re certainly going to be busy.

It's nice when Epic takes on patent trolls and other bad actors in the industry. They do great when they…