Top News

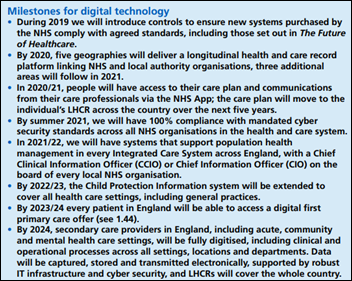

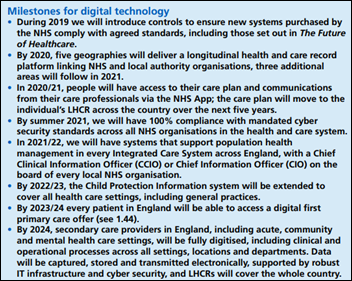

In England, NHS issues a long-term plan that calls for technology to:

- Improve patient access and the ability to self-manage health

- Give clinicians access to patient records from any location

- Apply best practices using clinical decision support and AI

- Apply population health prediction techniques to assign resources accordingly

- Capture data automatically to reduce administrative burden

- Protect privacy and give patients control over their medical record

- Link clinical, genomic, and other data to improve treatments

Reader Comments

From Jaye P. Morgan Gong Show: “Re: JP Morgan Healthcare Conference. I really like your post about the moneyed investors dodging the homeless on San Francisco’s sidewalks, but let’s remember Jonathan Bush stopping to administer CPR while he was walking down the street. Of course, we know what happened to him.” That unscripted drama from 2016’s conference said a lot about the character of the former Army medic and EMT, who didn’t hesitate to hit the dirt in his expensive suit to perform CPR. He explained at the time, “It was a lot like the healthcare industry: a lot of people were standing around tweeting about it, but no one was trying to do anything about this guy lying in the street. So I was like, turn him the f*** over! It was really dramatic. It was intense. The crowd was rooting for us.” Among the beauty queen sashes I ordered for that year’s HIStalkapalooza was one for JB that said, “I CPR’ed some random guy.” Meanwhile, Elliott Management’s Paul Singer had best hope that JB isn’t the only bystander if he goes to ground.

From Info Blocker: “Re: health system not sharing information with an HIE. That’s not like Epic.” Epic isn’t the problem here, it’s that one of their customers that doesn’t want to share patient information. Suggesting that EHR vendors are the bad guys distracts from reality. You only need to find one user of any EHR system that is sharing data by any means (HIE, Carequality, CommonWell, API, internal app, etc.) to disprove the idea that it’s not possible for that system to share information. The only way the vendor is the villain is if they charge unreasonable fees to make it happen.

From See Me, Feel Me: “Re: National Federation of the Blind. Is suing Epic for discrimination, saying that Epic’s failure to support screen readers prevents blind people from working in Massachusetts hospitals.” That’s actually old news from July of last year. The organization does of lot of suing for inaccessible websites, self checkouts that don’t work well for the blind, universities that don’t make every function and benefit accessible, and hospitals that don’t offer all materials in Braille or electronic form. Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires the federal government to make its own technologies usable by the disabled, but I don’t think the requirement extends further and I’ve only heard of it in the context of public web pages. I can’t imagine that Cerner – the federal government’s most expensive IT system in history – is natively accessible, so if it supports use by the blind, it’s probably through a third-party screen reader. Good intentions aside, I don’t know how someone who is blind could navigate information-packed displays that require clicking, choosing drop-downs, and displaying dynamic patient information. The lawsuit notes that Epic’s patient-facing applications have been made accessible and concludes that “Epic thinks that blind people are only fit to be patients, not healthcare workers.” I’m not sure the sarcastic tone and claims of discrimination will win friends and influence people.

HIStalk Announcements and Requests

We’re putting together our HIMSS19 guide that features HIStalk sponsors, so if your company is exhibiting or attending, contact Lorre to get our information collection form about your booth, giveaways, or activities. You’re probably spending a fortune to be there, so you might as well get some free exposure. She also convinced me to offer some sweeteners to cash-strapped startups who sign up as new sponsors, especially those who realize that their exhibit hall time leaves them out of the spotlight for the 362 days of the year afterward.

HIMSS will have some holes in its agenda if the federal government shutdown continues for 33 more days, which I assume would leave some attendees and presenters unable to attend.

Ellkay sent some fun stuff my way (via Lorre) for the holidays – a beautifully packaged sampler box of their honey (from their rooftop bee hives) and a really cool drawing of their Christmas party guests with a find-the-object game included. I’m generally indifferent to unimaginative corporate giveaways, but Ellkay does it perfectly in not only providing something novel and useful, but that also expresses who they are.

Webinars

January 17 (Thursday) 1:00 ET. “Panel Discussion: Improving Clinician Satisfaction & Driving Outcomes.” Sponsor: Netsmart. Presenters: Denny Morrison, PhD, chief clinical advisor, Netsmart; Mary Gannon, RN, chief nursing officer, Netsmart; Sharon Boesl, deputy director, Sauk County Human Services; and Allen Pendell, SVP of IS and analytics, Lexington Health Network. This panel discussion will cover the state of clinician satisfaction across post-acute and human services communities, turnover trends, strategies that drive clinical engagement and satisfaction, and the use of technology that supports those strategies. Real-world examples will be provided.

Previous webinars are on our YouTube channel. Contact Lorre for information.

Acquisitions, Funding, Business, and Stock

Physician and hospital information publisher Healthgrades acquires Influence Health, which offers web services, listings, reputation management, and CRM.

Change Healthcare and Experian Health will combine their healthcare network and identity management capabilities, respectively, to create an identity management solution.

Patient engagement technology vendor Vatica Health acquires the technology of the defunct CareSync, for which it made a $1 million stalking horse bid to the bankruptcy court in October 2018. CareSync, founded in 2011, burned through nearly $50 million in funding before abruptly shutting down in June 2018.

Analysts predict that Amazon will create Prime for healthcare, which could focus on offering lower drug prices via its acquired PillPack mail order pharmacy, Alexa services, using its recently announced medical records analytical service to scribe clinical encounters, and providing services such as telehealth and medical devices.

Patient matching technology vendor Verato raises $10 million in a Series C funding round, increasing its total to $35 million.

Sales

- St. Luke’s University Health Network (PA) signs a three-year Epic managed services agreement with HCTec.

- Boston Medical Center Health System chooses ZeOmega Jiva for advanced care management in its Medicaid ACO.

People

CHIME names Stanford Children’s Health CIO Ed Kopetsky, MS as 2018’s John E. Gall Jr. CIO of the Year.

Isaac “Zak” Kohane, MD, PhD (Harvard Medical School) joins the board of Inovalon.

Announcements and Implementations

Vocera launches a new hands-free, voice-powered Smartbadge that offers a larger color screen, improved audio, a dedicated panic button, and extended battery life.

Another 12 health systems representing 250 hospitals join Civica Rx, which will manufacture its own generic drugs – many of them in IV form — to save money and reduce shortages.

Withings will offer consumers a less-expensive EKG device than the Apple Watch with its $129 Move ECG, which hasn’t yet earned FDA’s marketing clearance. AliveCor’s $99 KardiaMobile came out two years ago as the first and arguably best of the lot.

Omrom launches a $499 blood pressure watch that uses an inflatable cuff built into the band rather than the usual questionably accurate optical sensors. It also announces Complete, which adds EKG capability to the blood pressure monitor.

AT&T and Rush University Medical Center will create the country’s first 5G-enabled hospital and will explore ways that a faster cellular network can improve operations and patient experience.

California health data network Manifest MedEx goes live on NextGate’s EMPI.

Other

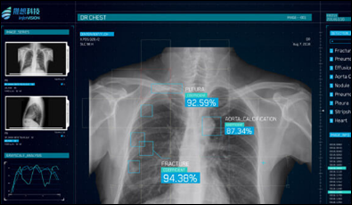

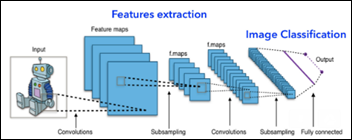

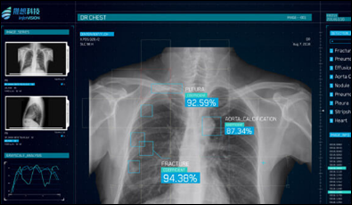

Wired magazine notes that China’s healthcare AI efforts, such as imaging analysis, benefit from that country’s less-rigorous privacy regulations that allow vendors to train their systems using millions of readily available patient images. An example is InferVision, which is being tested at Wake Radiology (NC) and Stanford Children’s Hospital.

Vox finds that the ED of taxpayer-funded Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital intentionally remains out of network for all private insurers, which the hospital explains is necessary to generate the money it needs to offset charity and Medicaid care. The hospital billed a 24-year-old woman whose broken arm was treated in its ED $24,000 (12 times the Medicare price), of which Blue Cross paid $3,800, leaving her on the hook for over $20,000.

A study published in Health Affairs finds that the 20 top-funded digital health companies have had minimal documented impact on disease burden or cost, with few published studies and an avoidance of measuring outcomes in sicker patients.

A large-scale consumer survey by NRC Health finds that 80 percent would change providers based on convenience alone; long waits and lack of respect are big dissatisfiers; people want to provide feedback quickly after their encounter and preferably by email; and patients don’t care much about provider brand identity and instead focus on their experience with individual clinicians.

Observer polls a panel of experts to name its 20 best “flyover tech” digital health companies that aren’t on either coast:

- Bind (MN) – insurance management for consumers

- Solera Health (AZ) – connecting patients to community organizations and apps

- NightWare (MN) – intervention for PTSD-caused nightmares

- ClearData (TAX) – cloud computing and information security

- Healthe (MN) – eye protection from computer device blue light

- MyMeds (MN) – medication adherence

- Visibly (IL) – online vision testing

- Higi (IL) – health kiosks

- HistoSonics (MI) – non-invasive treatment robotics

- Lumea (UT) – digital pathology

- Springbuk (IN) – actionable health insights

- Sansoro Health (MN) – healthcare data exchange

- LearnToLive (MN) – online mental health treatment

- Smile Direct Club (TN) – teeth straightening aligners

- SteadyMD (MO) – remote primary care that matches the lifestyles of patients and doctors

- Collective Medical (UT) – ED patient data sharing

- Limb Lab (MN) – prosthetics

- Upfront Health (IL) – care journey “next best action”

- AbiliTech Medical (MN) – robotic assistance for those upper-limb with neuromuscular conditions

- Vivify Health (TX) – remote care mobile devices

Tennessee pays contracted doctors a piecework rate for reviewing disability applications, with one of them finishing cases – of which 80 percent were denied — in an average of 12 minutes, allowing him to make $420,000 in the past year and $2.2 million since 2013. At least two of the contracted 50 physicians are felons, while others have had their medical licenses revoked.

In England, experts take a hard-eyed view of sloppily handwritten prescriptions after female patient irritates her eyes with what was supposed to be a soothing ophthalmic lubricant, which the pharmacist mistook as an order for a cream for erectile dysfunction. One might assume that the pharmacist ignored a series of computer warnings for issuing a drug for an inappropriate route of administration and patient sex.

Sponsor Updates

- Divurgent and Gevity will offer their combined healthcare information systems consulting expertise.

- Access and Dimensional Insight will exhibit at the MUSE Executive Institute January 13-15 in Newport Beach, CA.

- AdvancedMD announces the winners of its annual Healthcare Innovator of the Year Awards.

- Tampa Bay Tech awards AssessURHealth with its Emerging Tech Company of the Year award.

- The Best and Brightest names Burwood Group a Wellness Winner.

- The Chartis Group publishes a new report, “Why Your Provider Workforce Plan Isn’t Working.”

- The local news highlights UCSF Medical Center’s use of Collective Medical technology to help “frequent flier” ER patients.

- Divurgent and Gevity announce a strategic business alliance to expand their services across the US and Canada.

- DocuTap announces its 2018 student scholarship essay winners.

Blog Posts

Contacts

Mr. H, Lorre, Jenn, Dr. Jayne.

Get HIStalk updates. Send news or rumors.

Contact us.

I generally follow AP Stylebook style guidelines: Do not use all-capital-letter names unless the letters are individually pronounced: BMW. Others…