Rural Hospitals Need Federal Assistance to Strengthen IT Security Posture

By Kate Pierce

Kate Pierce, MSMIITA is senior virtual information security officer and executive director of the Subsidy program of Fortified Health Security of Franklin, TN.

The majority of my career in healthcare IT has been dedicated to working for a small and rural hospital, leveraging technology advancements to improve patient care and to keep those systems safe from cyberattacks. I spent 21 years with North Country Hospital in Vermont, starting as a systems analyst and working my way up to chief information officer and chief information security officer.

Growing up in a rural community in northeast Vermont, I have a deep understanding of the challenges faced by smaller hospitals, especially those in rural settings. I also understand how vital these organizations are to the communities they serve.

When I was asked to testify before the US Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee on the challenges that small and rural hospitals face in managing an effective cybersecurity program, as well as barriers to adequate funding and human capital constraints, it was an honor to do so, as this is a topic near and dear to my heart.

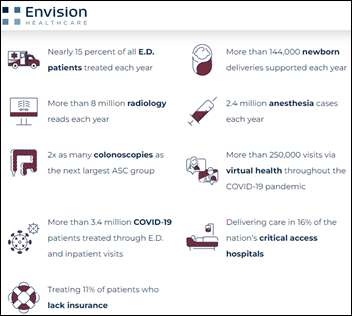

Even without the cybersecurity challenges, rural hospitals are experiencing unprecedented staffing and budget constraints. More than 40% operate in the red, and nearly one in three is at risk of closure. When it’s a daily challenge to deal with basic healthcare delivery while managing higher labor costs and shrinking margins, cybersecurity isn’t a top priority for most hospital executives.

Anyone who has ever worked in a hospital knows that change is constant. However, a cyberattack is among the most disruptive and devastating events that can occur within a healthcare environment. A 2021 study by the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) found that hospitals hit by ransomware often experience additional stressors that can be correlated with higher patient mortality rates.

This can happen at any facility, but criminals shifted their focus to attacking small and rural hospitals in 2022. Even though a successful attack against a smaller facility may yield less patient data or a lower ransom to release data, the reality is that they are often easier to breach and invariably connected to larger facilities.

When an urban or suburban hospital is hit with a cyberattack, it may inconvenience patients, but they often have other care options nearby. That’s not the case for rural hospitals. The nearest facility may be 40+ miles away, which doesn’t make it feasible to simply divert patients. Even if patients are diverted, nearby facilities can become overwhelmed, creating a cascading crisis throughout the community.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, as evidenced by a 2019 attack on an Alabama hospital that knocked out the hospital’s IT systems for three weeks and is believed to have resulted in the nation’s first fatality attributed to ransomware. According to the lawsuit, patient monitors were offline while the plaintiff was in labor, leading to insufficient monitoring of a fetus that was born unresponsive with the umbilical cord wrapped around the baby’s neck. Although the child was resuscitated, brain damage occurred, and the infant died nine months later. In a recent 2022 attack, a rural Washington State hospital was so overwhelmed that an ER nurse called 911 for help.

The urgency of improving the security posture of these small and rural facilities continues to escalate every year.

As the sophistication of cyberattacks continues to grow, the federal government should be stepping in to help secure these hospitals and keep patient data safe. As I testified to the Senate committee, implementing these four measures could improve the state of cybersecurity for our small and rural hospitals.

First, we must move beyond guidance and recommendations and create minimum standards for cybersecurity that all healthcare organizations must follow. These standards must be reasonable, effective, achievable, and continually evolving as cybersecurity requirements change over time.

Based on the items outlined in the Health Industry Cybersecurity Practices (HICP) document, recommendations can be grouped into five basic categories:

- Email security and protection

- Access management

- Asset management

- Network management

- Incident response

Simply put, regulators must spend less time suggesting and more time providing concrete solutions.

Second, we cannot leave our small and rural hospitals behind. We must create funding opportunities to allow all hospitals to meet the standards. Options include:

- Subsidies, which have found success among rural hospitals in other initiatives

- Grants, which may prove more difficult as smaller hospitals often don’t have grant-writing resources

- Incentives for small and rural hospitals to enhance security, a “Meaningful Security” type program modeled on Meaningful Use

- Enhancements in Medicare and Medicaid payments for eligible facilities, with hospitals showing how additional funds were used to boost cybersecurity

Third, we need better coordination of government cyber efforts for healthcare. While the guidance and services from government are appreciated, there is often a knowledge gap regarding the unique healthcare challenges that must be considered when applying cyber best practices in this sector. Due to time and budget constraints, many rural hospitals find it challenging to access or use available resources, so coordination must be streamlined to be effective.

Fourth, the federal government should establish a cyber disaster relief program, much like the assistance provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Such a program would provide this vulnerable sector with valuable resources in the event of attack, assist organizations in their recovery process, and increase the likelihood that hospitals could keep their doors open following a cyber-attack.

Overall hospital operating margins have been in negative territory for the past 12 months, according to a February hospital report from Kaufman Hall, and margins have decreased year over year for the past eight months. Operating margins are often higher for larger facilities that have outpatient clinics and more ancillary services than a smaller hospital can offer.

Adding to the challenging complexities, nearly 700 healthcare data breaches of 500 or more records occurred in 2022, according to the Office for Civil Rights. While the number of breaches is basically flat, the number of breached records topped 51 million for the first time, apart from the anomalous 2015, when just two breaches exposed 90 million records. Cyber insurance rates also continue to increase, with insurers demanding more monitoring and detection technologies that smaller facilities may not have if facilities can obtain insurance at all.

Because healthcare records are so valuable, hackers aren’t going to stop. Small and rural hospitals need help to protect their systems and patients, and these simple measures are a sensible path forward.

Comments Off on Readers Write: Rural Hospitals Need Federal Assistance to Strengthen IT Security Posture

Give ophthalmology a break. There aren’t many specialties that can do most of their diagnosis with physical examination in the…