It is incredibly stressful once you leave the Epic center of gravity. I have spent my ex-epic career wondering if…

EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 5/7/20

This week is National Nurses Week. I salute all the nurses who taught me what I really needed to know to be successful on the wards, since most of it wasn’t covered in the formal curriculum presented by the medical school faculty.

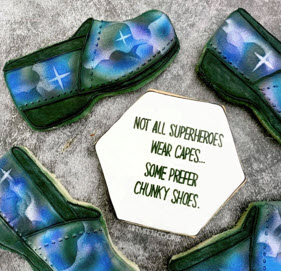

I came across this pastry shout-out to nurses from physician Cindy Chen-Smith @artmeetscookie and was blown away by the airbrushing. Whether you’re a superhero in chunky shoes, New Balance sneakers, sassy heels, or tactical boots – I salute you.

I also enjoyed reading the comments on National Nurses Day from Patti Brennan, director of the US National Library of Medicine (and a nurse herself). She notes, “While the Library can’t manufacture more time, fabricate personal protective equipment, or stand beside the bed of a patient in need, we can help nurses find freely accessible literature.” Brennan mentions special search strategies such as LitCovid, which I admit I’d never heard of. It’s a curated hub for tracking the most recent scientific information about our current situation and categories articles by topic and by geographic location.

I enjoy seeing the breadth and depth of the projects my clinical informatics colleagues are working on. This research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine last week looks at “Internet Searches for Unproven COVID-19 Therapies in the United States.” Since we’re looking at a disease with no reliable proven treatments there are plenty of ideas floating around the internet (and directly from political figures) that are catching people’s attention. The authors looked at internet searches that were “indicative of shopping for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine” by monitoring Google searches “originating from the United States that included the terms buy, order, Amazon, eBay, or Walmart” in combination with chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine.”

They cross referenced the data against the dates when Elon Musk and President Trump endorsed the drugs, as well as the date when news reports on treatment-related poisonings were published. The authors found that “queries for purchasing chloroquine were 442% higher following high-profile claims that these drugs were effective COVID-19 therapies.” Searches for buying hydroxychloroquine were 1389% higher. Searches for purchasing the drugs continued to remain high following news reports of their dangers, although at a lower level (212%).

In the discussion, the authors note that “Google responded to COVID-19 by integrating an educational website into search results related to the outbreak, and this could be expanded to searches for unapproved COVID-19 therapies.” I’m sure there will be more research questions to come in this area as the pandemic rages on.

Most of my physician colleagues have been doing at least some level of telehealth, and after a couple of months, some of them swear they don’t want to go back to in-person care at the same levels they practiced previously. Many patients don’t want to go back either, especially in economically depressed areas and among patients who previously had to travel long distances to receive treatment. A Stat news piece looks at patients in coal country, where the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) has seen a 3,700% increase in telemedicine visits.

One of the reasons for greater patient satisfaction during telehealth visits was noted by UPMC’s CMIO, who noted that who “doctors are able to type notes while facing the patient, instead of looking over their shoulders.” That seems like an operational / technical issue to me. Perhaps UPMC should look at reconfiguring their exam rooms and employing laptops on carts or a better type of device to make their in-person visits more hospitable. He also notes the struggle with initial visits, with patients succeeding on the second or third attempts.

Although many physicians are assuming that the wild, wild west of telehealth (non-HIPAA-compliant platforms, reduced requirements on service location) will continue, we’ll have to see what the payers decide to do. We’ve already seen many of the cross-state licensure waivers end, and there’s already a lot of financial pressure to return to the status quo. (How do you justify charging a facility fee when neither the provider nor the patient are in the facility? Inquiring minds want to know.)

As hospitals start to pass the peak of COVID-19 and clinical care teams start to learn to breathe again, the folks in finance are continuing to have increased anxiety. They have to figure out what it will take to make their balance sheets positive again, or at least less negative. A recent article featured Dan Michelson of Strata Decision, who discussed what CFOs will need to weather the long-term changes after the COVID-19 storm. I’ve chatted with Dan a couple of times, and he’s usually spot-on in his observations.

Among the things he recommends: rolling budget forecasting, adherence to coding guidelines for complications and secondary diagnoses, and being able to anticipate patient behavior changes, especially the desire for non-emergency procedures. Organizations will also need to truly understand their costs, including PPE, overtime, and additional supplies in the new world post-COVID. They’ll also need to understand the role of self-pay in their overall financial picture, since many patients have lost the health insurance that was tied to their employers.

Another issue in the “new normal” post-COVID is understanding how we catch up on diagnoses that were missed due to multiple months of delayed preventive services. A report from the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science looks at trends in the US for five common cancers. The report estimates that 80,000 cases may be missed across breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers based on decreased screening volumes in April compared to February.

I’m high risk for two of those conditions and am behind on my regular tests due to the closures, so I can definitely understand concerns about screening delays from the patient perspective. Interestingly, I’ve received no communications from either of the providers involved in my regular screenings, so I suppose I’m left to assume that their strategy for handling patient recalls during the pandemic was to just stop contacting people. That’s not much of a strategy for patients who might not be as compulsive about their health as I am. I’ll just keep bumping my calendar reminders forward a few weeks at a time until I hear the hospital is back in the screening business.

The American Academy of Family Physicians came out with a checklist for reopening practices to non-essential face-to-face visits. Usually their advice is pretty practical, but one bullet caught my eye. They recommend that common areas such as patient waiting rooms and staff break rooms should remain closed if possible. Although they recommend allowing patients to wait in their cars until it’s their turn to be seen, they conveniently avoided any recommendations on where staff should take breaks. In my travels, I’ve seen plenty of people eating in clinical care areas because they don’t have time to take an actual break or the office doesn’t have adequate facilities.

Seeing patients face-to-face in these new conditions is more tiring than before and staff do need a place to take a break (not to mention a safe place to take their mask off so their skin can breathe). They also call for staff to wear face masks, gowns, eye protection, and gloves when caring for suspected COVID-19 patients, We’re still in a shortage of gowns, so that’s just not realistic.

There was a recent story on “Good Morning America” encouraging graduates to donate their unworn gowns for healthcare providers to use as personal protective equipment. Although I appreciate the sentiment, I’m horrified that several months into this situation, we’re still in crisis mode. Will the surgeons be asked to wear hand-me-down graduation gowns to the operating rooms now that they’re starting to book cases? I think not.

Does your staff get to use the break room, or to do they take their meals in their cars? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Dr. Jayne! Thanks, as always, for your insights. On your point about exam room configuration; my former employer (an EHR company) had onsite primary care clinics for all employees that were also set up as somewhat of a showcase of how to “EHR” well. All the exam rooms had two armchairs facing a large monitor that the physician’s laptop was connected to. After the exam the doc would move the conversation over to those chairs to write up the note and finish the visit, making the act of writing the note more of a collaborative experience. As a patient, it felt a lot better than the doc plugging away on a laptop on their little stool while the patient sits on butcher’s paper.

Great post! Thank you.