I've figured it out. At first I was confused but now all is clear. You see, we ARE running the…

Book Review: “Bad Blood”

I’ll save you the $13.99 Kindle price right now. Theranos was a fraud in every possible way. Elizabeth Holmes was its paranoid, money-fixated mastermind who was enabled by media that were enchanted with the crowd-pleasing and unfortunately rare story of a young, female Silicon Valley founder. Holmes didn’t care a bit that patients were endangered by the company’s entirely inaccurate blood testing system. She was a paper multi-billionaire until a series of exposes in the Wall Street Journal took the company down and put her on “healthcare’s most reviled” leaderboard ahead of Martin Shkreli. Thanks for coming out, I’m here all week, try the veal.

Or, maybe the $13.99 is worth it just to see how the company used its heavyweight legal team and connections to keep the scam alive. Or for the guilty pleasure of reading how Holmes sweated as the noose tightened, eventually going all Hitler in the bunker as she realized that at 34, she would never be trusted or taken seriously again.

You’ll like John Carreyrou’s book if you’re a fan of “All the President’s Men” or “Spotlight” and would enjoy the dramatic (and overly dramatic at times) account of how the reporter bagged the story of a lifetime and then got to double-dip his WSJ salary by repurposing his work into a bestseller. He’s probably worth a lot more than Holmes at this point.

Everything about the company was an elaborate hoax and so was Holmes, coached to ditch her thick glasses, speak in a creepily low register, wear black turtlenecks, and make lofty pronouncements about changing the world. She was like a lipsticked Steve Jobs except her fake voice was deeper, she was even better at milking the reality distortion field except to commit fraud instead of inspire achievement, and instead of kicking a dent in the universe, she was sent kicking and screaming into shame and ridicule (with a vacation behind bars a distinct future possibility).

Like Jobs, she was petulantly demanding, leaving a trail of fired employees and board members who dared question whether the empress was indeed wearing any clothes other than that ever-present turtleneck. Her 20-member armed security detail marched out employees who questioned the company’s patient-endangering technology that never worked. She oversaw her empire from an office she had designed as a replica of the White House’s Oval Office, which is about as weird as you can get.

The book opens with the company’s CFO playing his dutiful Silicon Valley role in inflating his already-inflated financial projection at Holmes’ insistence that she needed one of those hockey-stick growth charts like everybody else in Silicon Valley trots out while trying to keep a straight face. The CFO wasn’t too inquisitive about why Holmes refused to show him the drug company contracts on which his fantasy financials were based. His downfall came when he questioned Holmes about a demonstration of her blood testing machine that he knew didn’t actually work, charging Holmes (accurately) with simply faking the whole thing. She fired the CFO on the spot and the board didn’t press her for a reason (hello, clueless board). He was the company’s first and only CFO – despite heavy investment and a $9 billion paper company value, Theranos never had one again (hello, clueless investors).

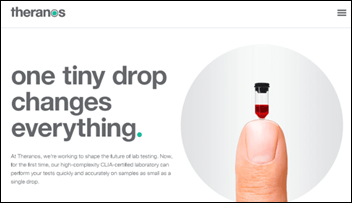

Holmes dropped out of Stanford’s chemical engineering program after two semesters and wrote a patent application for an arm patch that would both diagnose and treat medical conditions. Her only fear in life was needles, which she vowed to eliminate for blood draws in favor of a finger stick, which sounds great to a 22-year-old college dropout who didn’t know or didn’t care that entire companies are filled with experts who have tried and failed to make that idea work. The sample size is too small, the dilution is too error-fraught, the repeated microfluidic flow through the testing machine is too complicated, and the skin material that is sucked up along with the blood always throws the results off.

Asked to describe how its product works, Holmes provided The New Yorker with a “comically vague” explanation:

A chemistry is performed so that a chemical reaction occurs and generates a signal from the chemical interaction with the sample, which is translated into a result, which is then reviewed by certified laboratory personnel.

Despite having no product, the business plan Holmes cooked up was brilliant. She envisioned drug companies paying her fortunes to perform home blood testing of clinical trials subjects, claiming that real-time reporting could save them 30 percent of their research costs and alert them to stop the therapy if patients experienced problems. Holmes was healthcare illiterate, but at least she knew that in search of health riches, you go where the money is (drug companies).

Holmes whipped employees into working crazy hours, spied on their email and telephone calls, hired private investigators to follow them, and didn’t allow company groups to interact with each other for fear of compromising her intellectual property. Her second-in-command was Sunny Balwani, her secret lover who was 18 years older than she. She marginalized the company’s board as “just a placeholder” that she charmed into giving her 99.7 percent of the voting rights, rendering the aged former heads of state and billionaires irrelevant as they joined the company’s investors in breaching their fiduciary duty. They treated her like a darling granddaughter who could do no wrong, smacking their lips approvingly at the inedible Easy-Bake Oven cake she proudly served them.

The blood testing technology didn’t work, so engineers jury-rigged a glue-dispensing robot to move pipettes around. Holmes immodestly named it the Edison. It was fraught with the same problems that plagued everything that Theranos ever designed – it could perform only a few tests, it wasn’t suitable for home use, and it ran only one sample at a time. Most importantly, it delivered inaccurate results. She had a very slick, Apple-looking case designed for it, though (it was not known to wear black turtlenecks).

Theranos ran an admirable “fear of missing out” scam on Walgreens, playing on that company’s fears that CVS would sign a deal first. Walgreens invested heavily even though Holmes refused to show them her lab and wouldn’t allow them to run side-by-side samples with commercial labs to verify the Edison’s accuracy (hello, clueless due diligencers).

Theranos avoided CMS and FDA oversight by claiming that its technology was “laboratory-developed tests” that fall between their respective jurisdictions, with the government predictably paying no attention. All Theranos had was a CLIA certificate and lab that was being run by a dermatologist with no lab experience. Holmes tried to work her connections to have the military use her product, only to become infuriated when a military expert said she would need an IRB-approved study and FDA approval. Holmes tried to get him fired. It didn’t matter anyway since she simply lied in claiming to anyone who would listen that the military was using Theranos in Afghanistan battlefields. She said it, so it must be true, and at some point she probably repeated it enough times to believe it herself.

Also scammed was the grocery chain Safeway, which envisioned a sexy future in wellness. It spent $350 million to add swanky Theranos testing stations to its stores somewhere back between the meat department and the rotisseried chickens.

Theranos started developing the MiniLab in 2010. Its only innovation over commercial machines was a smaller footprint for home and retail use. Holmes kept a straight face in calling it “the most important thing humanity has ever built.” She hired Apple’s former marketing company for $6 million to orchestrate a splashy product rollout and her own photo shoots.

Theranos couldn’t make its technology work in time to meet a Walgreens deadline, so Holmes simply bought a bunch of commercial blood testing machines and hacked them to try to make them work with the fingerstick samples. The friendly, fawning press asked no awkward questions. Her orchestrated fame emboldened her to fudge the numbers even more – she assured one investor that the company would make a $1 billion profit in 2015, while nearly simultaneously telling another investor that it would be $100 million. Her patient result numbers were equally all over the place, as the company performed untested processing on the modified commercial machines in its Phoenix-area rollout at Walgreens. They were just Fedexing samples back to California, which introduced another problem Theranos hadn’t thought of – the sweltering Phoenix summer sun was ruining the samples as they sat on hot Fedex planes. Doh!

The hoax started to unravel when a pathology blogger noticed that a paper Holmes co-authored had been published by a pay-for-play online journal in Italy and it involved a study of only six patients. The blogger contacted Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou, who conducted his own test by having blood drawn at an Arizona Walgreens. He thought it was odd that it was a traditional needle draw rather than a finger stick, becoming even more puzzled when his same tests performed by LabCorp gave wildly different results.

While Carreyrou was investigating, the Theranos deception continued. The machines kept screwing up during demonstrations, so engineers rigged a “waiting” icon on display so the company could blame connectivity problems and then run the samples later on commercial machines that actually worked. Holmes would encourage investors and reporters to have blood samples drawn in her offices and would show them the sample being inserted into the MiniLab, but as soon as they left, employees would pull out the sample and run it on a commercial lab machine.

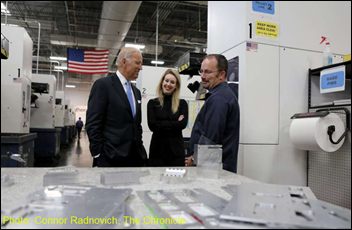

In honor of a visit by Vice-President Joe Biden, Theranos built a fake lab in a conference room, stacking up non-functional MiniLabs and ordering employees to stay home in case anyone asked embarrassing questions.

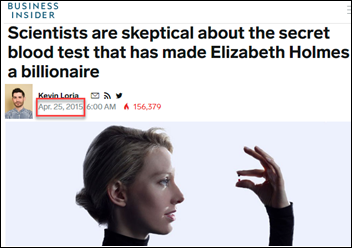

Carryrou’s first article created a firestorm, although Business Insider’s Kevin Loria scooped him by a full six months in running a skeptical article quoting scientists in April 2015 – he really should get the credit. Many people defended Holmes, while others questioned how a medical company’s board and investors could have only healthcare-inexperienced people.

Holmes took to the airwaves to defend her company, proclaiming, “When you work to change things, first they think you’re crazy, then they fight you. And then all of a sudden you change the world.”

You know the rest. FDA declared the nanotainer to be an unapproved medical device. A surprise CMS inspection said Theranos was posing immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety. Holmes made Balwani her sacrificial lamb, firing him and breaking up with him. All Edison test results were voided, Walgreens and Safeway ended their Theranos partnership, Holmes was banned from the industry, and everybody involved sued Theranos, which had burned through $900 million of investor money and was rapidly going broke defending itself. As icing on the cake, the SEC began an investigation, declaring Theranos to have been a “massive fraud” from the beginning.

I’d like to think that most of us in healthcare eventually saw through the Theranos scam, or at least would have been skeptical enough to ask the questions that its investors and Holmes fanboys didn’t. The company made big claims without publishing peer-reviewed data. Its value proposition wandered – was the story the finger stick, the consumer access to blood tests, or the cost-lowering threat to LabCorp and Quest? Dropouts in their early 20s might well start technology companies like Facebook, but the Theranos board and leadership team were remarkably inexperienced and naive about healthcare and the huge players entrenched in it that had already already tried and failed to commercialize fingerstick testing. They also had the advantage that in terms of lab services, it’s all about draw-station locations and the economy of scale of running thousands of tests per minute through a highly automated factory, and Theranos would have needed to scale to thousands of times its volume to take even 1 percent of their market.

Theranos is a good reminder to healthcare dabblers. Your customer is the patient, not your investors or partners. You can’t just throw product at the wall and see what sticks when your technology is used to diagnose, treat, or manage disease. Your inevitable mistakes could kill someone. Your startup hubris isn’t welcome here and it will be recalled with great glee when you slink away with tail between legs. Have your self-proclaimed innovation and disruption reviewed by someone who knows what they’re talking about before trotting out your hockey-stick growth chart. And investors, company board members, and government officials, you might be the only thing standing between a patient in need and glitzy, profitable technology that might kill them even as a high-powered founder and an army of lawyers try to make you look the other way.

Told her to change the name of company to TheRawAnus

Well said! We have seen big players (Microsoft) attempt to faciliate “change” but don’t know or understand our world. It’s not about profit. It’s about the patient. They will never get that.

Read it in two days. Couldn’t put it down, despite that it is the most depressing, soul-crushing stuff.

This woman is a narcissistic maniac…Stanford should add a class on humility and humanity. She reminds me of McAfeee and even the Enron clowns.

I’m strongly of the view that all STEM programs must include History, Philosophy, and Ethics courses as core requirements in order to obtain a degree.

I mean, can you even IMAGINE?

$9 billion and the product doesn’t even do what it was advertised to do. We’ll never see a scandal like that again.

Given your comment history, wondering if this is a vague dig at Cerner’s government work

Was is really that vague?

Mr. H., this is one of the best things you have every written. Your passion, which is what makes HISTalk relevant, comes through, and you rightly point not merely to Elizabeth Holmes as the culpable party but to the multiple, willfully clueless parties who took way, WAY too long to question this ridiculous charade.

Thanks, but all I did was summarize what Carryrou wrote in choosing the most interesting parts that were new to me. He did the heavy lifting even though Theranos was threatening him and the WSJ constantly — more specifically, their $1,000-per-hour attorney turned board member David Boies (another bad company choice — board members are supposed to protect investors, not defend the company of every perceived wrong).

Great writing and a great review! You should do more of these.

Happy to. Let me know what I should read!

My review of your review. Having chronicled for my own readers the Fraud That Is Theranos, your article added a caution to all those healthcare ‘revolutionaries’ out there that we are holding their lives, not their watches. http://telecareaware.com/the-theranos-story-ch-52-how-elizabeth-holmes-became-healthcares-most-reviled-histalks-review-of-bad-blood/