Today marked the closing of AMIA, with presentations in the morning and a final keynote by Robert Wachter, MD, one of the founders of the hospitalist movement. I had been looking forward to the keynote, but due to an unforeseen crisis at one of my clients, I had to leave earlier than planned. That’s the hazard of being a workforce of one. At least I have enough clean clothes in my bag to pull off an urgently-scheduled board meeting. Unfortunately, my flight was delayed, so I’m now camped out at the San Francisco airport catching up on work.

I mentioned the other day my disappointment at not being able to attend Monday’s ONC Listening Session. ONC Chief Health Information Officer Michael McCoy, MD graciously emailed me to apologize because they did indeed have room for more attendees. I sorted out the problem and the miscommunication was on my end, with my new (and very part-time) assistant confusing the ONC session with another meeting next week that I was also trying to register for. I haven’t had an assistant since I left the health system and I am reminded that “what’s the status on that meeting for Monday” is an ambiguous question. I truly appreciate his reaching out and I apologize for the confusion. I heard in passing that the session went well. I’d be interested to hear specific comments from anyone who attended.

My absolute favorite panel of the conference was on Tuesday and was titled “What Could Go Wrong? Migrating From One EHR to Another.” Since I have done quite a bit of work in the migration and conversion space, I was interested to hear how my experiences stack up against those of others. I was hoping to have the slide deck before I wrote about it, but it doesn’t look like it has been posted yet. Luckily for this session I joined the legions of people snapping pictures of the slides, since not only was it content rich, but had some outstanding clip art ideas.

The session was heavily attended. After some excessive microphone checking “check check, hey hey, check check” it was off to a great start. Richard Schreiber, MD, CMIO of Holy Spirit Hospital (a Geisinger affiliate) talked about the published research literature to date looking at system migrations. It’s scanty at best, with only five peer-reviewed studies and a few surveys. Not surprisingly, there are numerous blogs and anecdotal stories, however. One study looked at a hospital one year after migration and found heavy access of the legacy system. The hospital’s legal team consulted with AHIMA and recommended that even with a data conversion, they may need to have the legacy system live for up to 10 years in a read-only status.

Data conversions were a hot topic, specifically the fact that customers might not get what they asked for or paid for. There was discussion around the need to manage expectations around a system transition, as some sites have noted lower satisfaction due to high expectations that were unrealized. There was some interesting data in some of the studies: that 40 percent of providers are on their second, third, or even more EHRs. As practices and hospitals continue to consolidate, this will only continue. My former employer is on its second ambulatory EHR headed for its third and is consolidating multiple hospital systems into one. Schreiber noted that EHR changes often accompany cultural and political shifts in addition to ownership changes.

He went on to talk about the “think freeze” that occurs around EHR upgrades. Because of code cut-offs and system and environment freezes there is less consideration of what the end users need. With a migration, this is even worse, with that freeze occurring for potentially years rather than months or weeks as the organization prepares for the transition. Community hospitals are particularly challenged by a lack of resources, training, and support. Physicians experience “large efforts with small teams” that mean “army swarms and then retreats.” For providers who aren’t in the hospital consistently, they may have limited support after a go-live.

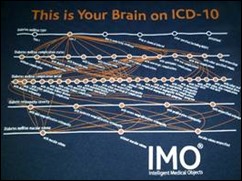

Sociologist Ross Koppel, PhD of the University of Pennsylvania then took the podium. I got a kick out of the fact that his bio in the AMIA app lists him as, “Among most hated by some vendors, but appreciated by clinicians.” He talked about the fact that the average hospital has between 150 and 400 separate IT systems that link with the clinical system, not counting outside systems such as reference laboratories. “Each one is an opportunity for a screw-up” also known as a “vulnerability.” He talked about how “hospitals are unique fiefdoms” and the fact that new systems bring a loss of institutional memory, such as the work-around done by a unit secretary to actually get things done for patient care.

He discussed the problems that customization can cause with system migrations. Looking at two different Epic systems in neighboring hospitals revealed that the systems were related “like Spanish and Italian” but that “data and interfaces differed enough that assumptions of similarities could be treacherous.” Having gone live on Epic at two community hospitals in the same summer several years ago, I can agree with that assertion. Koppel also discussed issues with calculating return on investment and the difficulties with hospital bookkeeping on some projects. ROI research is also commonly done by vendors, confounding the issue. He discussed the $1.7 billion implementation at Harvard as being $400 million in software, $700 million for Deloitte, and the rest internal.

The next presenter was John McGreevey III, MD of the University of Pennsylvania, talking about the PennChart project. With six hospitals, 2,524 beds, and 84,000 admissions a year, this is a massive project. He talked about their lessons learned:

- Not enough operational leaders. He felt they needed three to four times what they had.

- No health system budget for clinical subject matter experts to design note templates, order set content, etc. EHR tasks were added on to their regular responsibilities. Doing a project like this without SMEs and adequate human infrastructure is like a fire department that tries to fight a house fire by hiring firefighters after it’s already started and paying them zero.

- Not enough “internal housekeeping” prior to the project. He stated that after signing a contract, vendors should tell the hospital “thanks for your check – call us in a year” after you’ve done your housekeeping.

- Vendor liaisons were relatively green – most had only one or two implementations under their belts. They could not cite definitive best practices from other academic medical centers or make good recommendations about decisions. He did note, though, that other customers were very gracious with their time despite being heads-down in their own implementations. This might be a future role for AMIA, as a clearinghouse for best practices.

- Build decisions may have created barriers to interoperability. Standardized approaches to naming, organizing data, etc. are needed. This results in “big data we can’t use and can’t share.” Vendor guidance often oversimplified complex decisions, leading to rework.

- Siloed project teams led to lack of understanding, fragmented work, and wasted time.

- They got a late start on changed management, leading to lack of shared urgency or mission. He recommends “bathing the organization” in change management before any work starts, not just before go-live.

Catherine Craven, MLS, MA of the University of Missouri closed out the panel talking about system migrations among Critical Access Hospitals. There is even less data on these hospitals, because as of 2010, fewer than 3 percent had EHRs. A good number of facilities (300) haven’t attested for MU Stage 1 yet, although 150 did receive Adopt/Implement/Upgrade funding. She completed her doctoral dissertation last year and studied four hospitals. The statistics are shocking: many CAHs have less than 30 days’ cash on hand and often the cost of an EHR is between 75 percent and 100 percent of total cash assets. In other words, these hospitals have to bet the farm on their EHR project. Craven did an excellent Peggy Lee impersonation.

She went on to note that the CAHs she visited did only basic installations without workflow transformation. They often relied wholly on vendors because there was no budget for consultants. They were also rushing to implement, with one hospital having less than five months from contract signing to its go-live.

Tuesday afternoon I ran into a friend from the VA and attended a session on human factors. The room was packed as presenters shared their work. Topics included observational studies of user workflow while accessing both the EHR and a RHIO, cognitive demands of EHR via task analysis, and cognitive support for ICU data. I noticed Brian Dixon in the front row with his jacket from The Walking Gallery, but wasn’t fast enough to get a picture.

Throughout the conference, there were a couple of things nagging at me, although they are decidedly first-world problems compared to the plight of the many homeless in San Francisco:

- The use of “MD” as a substitute for physician, not only in presentations, but in the official printed publications. There are plenty of DO informaticists and international physicians with slightly different degrees.

- Interchangeable use of the terms “sex” and “gender.” Especially among people who are talking regularly about coded data and the need for specificity and interoperability, it’s time to learn the difference between the two.

- Continued references to Epic, even if they’re veiled. We know it’s the predominant system among academic medical centers, but it’s not the only system out there. I got a kick out of two physician users of a less-prominent EHR vendor who looked at each other and said, “Ours does that” when the speaker lamented a particular lack of Epic functionality.

- Late arrivals. The conference encourages people to drop in and out of sessions to “follow the conference buzz,” but that doesn’t mean you need to enter the room like a herd of elephants or climb over and disrupt those that area already there.

- Seating arrangements included excessively close chairs that nearly prevented people from sitting next to each other unless they were both less than 14 inches wide. This led to a lot of empty chairs between people, but that made it a little easier for those with large bags that they’re using as a mobile office. Also the rows were close front to back, making it difficult for people to slip in and out without tripping over legs, feet, and bags.

On the flip side, I was happy to see one of the presenter’s children at the conference, complete with badge and ribbons. I’m sure the conference was a highlight for both of them. I also saw a couple of dogs at the conference, which made me chuckle. They didn’t appear to be service or support dogs, but they were well behaved.

I was considering attending AMIA’s iHealth conference in May since its more focused on clinical and operational informatics. I may already have something on the docket for that week, but would be interested to hear people’s impressions on that conference’s usefulness to CMIOs vs. the annual symposium. I want to make the most of my conference budget, and considering that this one set me back almost $3,500, I want to choose wisely. For those of you in the MOC trenches, that’s nearly $175/hour for the sessions I attended.

What’s your favorite conference? Email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Fun framing using Seinfeld. Though in a piece about disrupting healthcare, it’s a little striking that patients, clinicians, and measurable…