I use a wiki and was exploring some of the extended character sets. I was startled to learn that the…

Curbside Consult with Dr. Jayne 3/18/19

There was another big story about telemedicine in the news this week, this time about a young man who had to undergo what sounds like a competency evaluation via video prior to signing a “do not resuscitate” document. Regardless of the telemedicine situation, the story is heartbreaking. A young man with testicular cancer is dying. His wife did not have power of attorney, and it sounds like the hospital was concerned about his ability to legally sign the document.

The focus of the story is the telemedicine angle, whether it’s poor connectivity, level of compassion, etc. I haven’t seen a news piece, however, that addresses the other issues that are brought to light by the situation. Namely, how it got to that point in the first place.

This was a patient with a recurrence of testicular cancer, which is a serious situation. Of course, we don’t have all the medical details of the case, but there are some non-medical issues at play here. For an oncology patient with a young family, we should hope that a comprehensive advance care planning session should include not only discussion of end-of-life wishes, but also the need to have the appropriate legal documents in place. These discussions need to happen early in treatment, while the patient can discuss with their family and make good decisions and before events unfold that put decision-making capacity in question.

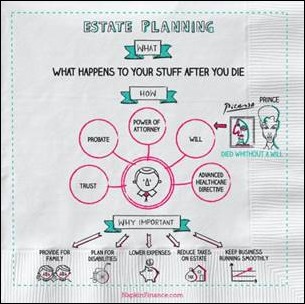

Seeing the pictures of his young daughter made me wonder if he had a will, and if so, did the attorney involved (if there was one) also advise on advance directives and power of attorney documents? We always think about healthcare organizations supporting patients in these situations, but what about legal organizations? Are there channels for attorneys to volunteer services to families like this to ensure they have the supports they need? Why is it always the physicians and hospitals that bear the brunt of responsibility for failure in these heart-wrenching situations?

I know I’ve covered this topic before, but everyone needs to have these conversations, whether you’re sick or well. We never know what is going to happen, what illness or speeding car might strike us down. However, in the situation where someone potentially has a terminal illness, it should be happening without fail.

I don’t know about the laws in the jurisdiction where this story occurred, whether a psychiatrist specifically was needed for the determination of capacity or whether anyone else in the hospital could have done it. We don’t know if this was the middle of the night or the middle of the day. Perhaps the video consult was offered up as a way to speed things, if it would have taken longer to bring the appropriate clinician into the hospital. There aren’t a lot of facilities that keep psychiatrists in-house at all times, so maybe the choice that was made was the best one at the time even if it didn’t play out as the family expected. Approaching end of life is challenging enough even when all the paperwork is in place and the family is supportive of the patient’s wishes.

My thoughts go out to everyone involved. I encourage everyone out there, young or old, healthy or not, to have these conversations with your family members and to make sure you have the right paperwork in order to make the best of a terrible situation when the time comes. Eventually, death comes for us all.

Another situation I ran across this week that demonizes technology without addressing other “comorbid conditions” was an interview with Eric Topol. This time, EHRs are the bad guy, but artificial intelligence is going “make healthcare human again,” at least according to his newest book. I don’t know Dr. Topol other than by what I have ready in his books and in various interviews, but I’m awfully tired of people who seem to have all the answers to what are undoubtedly very complex problems.

Topol lists EHRs as “the single worst part of the deteriorating doctor-patient relationship.” Although I agree they’re a factor, I personally think the worst part of the deteriorating relationship is the devaluation of the relationship itself. Because our medical system in the US is so broken, people no longer value the concept of a lifelong primary care physician who is going to know you as a patient and understand what optimal health means for you. We’ve sacrificed it on the altars of cost and convenience because those elements are more important for many of the people in our society. We’ve decided that it’s more important to treat populations (numbers) than people (outliers) and have incented people to behave in a way that supports that. Providing clinical expertise has become transactional and commoditized.

I feel this acutely every day that I see patients, especially on those days when I am part of a story that starts with a seemingly minor medical problem and ends with, “I went to the urgent care and now I have cancer.” I never dreamed that as an urgent care physician I would diagnose the number of life-threatening conditions that I see on a regular basis. It falls to us because people don’t have primary care physicians, they can’t get in to see them, or they can’t afford to get medical care. Once I diagnose people and refer them to the appropriate subspecialists, they’re generally lost to me unless they follow up with a card or a note. However, they don’t leave my mind and their stories haunt me every time I see a patient with a similar presentation.

Fixing EHRs isn’t going to fix the fragmentation in care. First, we have to decide as a society that unfragmented care is important. We have to decide that primary care and public health are important and we have to support those decisions with our pocketbooks.

I have a friend at a large health system that just spent half-billion (with a “b”) dollars on an EHR rip-and-replace. How much was she able to get as a grant for a school-based health clinic to serve children who never see a physician or other clinician? Zero. She had to pull together a coalition of community organizations to fund it despite her non-profit employer sitting on one of the largest cash reserves in the nation.

Topol says EHRs are “uniformly hated” and that’s just not the case. Sure, we dislike clunky interfaces and click-happy screens, but we sure love being able to process a drug recall in 90 seconds and notify 10,000 patients with a dozen clicks. We never loved our paper charts (and some of us hated them), but in reality, how many people “love” the tools they use for their work? Do mechanics love their tools? Do bankers love their tools? Do teachers love smartboards more than they loved chalkboards or whiteboards? Talking about the dynamics of love/hate just raises emotions and makes it harder for us to rationally evaluate what we’re really working with and how we are able to use it well vs. struggle with it.

Topol does at least give a passing mention to the healthcare disparities in the US, noting that increased use of AI and data “could make things much worse if these tools are only provided for affluent people.” We’re already at that point, where people struggle to pay for basic healthcare. If we can’t universally deliver vaccines (proven cost effective) to all people, are we really going to be able to afford gathering and analyzing all their data (not yet proven to be as spectacular as some people think)?

Fixing the EHR might make the day smoother, but it’s not going to fix the major underlying issues in healthcare. It’s not going to fix a hospital system that lowballs physician salaries in the name of value-based care, but turns around and builds a multi-million-dollar imaging center. It’s not going to fix an insurer that will pay $30,000 for a gastric bypass for a teenager after it wouldn’t pay $2,000 for an intensive weight management program that might have prevented or delayed the need for bariatric surgery. It’s not going to fix nursing ratios on patient care floors that are inhumane, not to mention unsafe.

I don’t have all the answers, but I’m pretty good at stirring up a discussion. What do you think is the worst part of the deteriorating patient-physician relationship? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Regarding technology and the state of patient/physician relationships… I’m in general agreement but would add another factor. In today’s environment physicians are much more mobile than they used to be. In days gone by, (and I’m old enough to remember) physicians were a part of the community they served. Usually long term to the point of being a ‘fixture’. With most of today’s physicians being employed by systems it is far too easy and tempting to jump ship to a new environment that offers more money, better technology, less call and a host of other advantages. You state that ” people no longer value the concept of a lifelong primary care physician who is going to know you as a patient and understand what optimal health means for you” and I think that is a true statement. I also think that statement applies to both patient and physician. How many people today can say they have had the same PCP for most of their adult lives? I’m sure that number grows smaller every year.

We are way too quick to see the latest tech innovation as the silver bullet fixing all that ails healthcare. While quality may improve somewhat, the most noticeable impact is increased complexity and cost.

Thanks for this article Dr. Jayne. I found this to be thought provoking and insightful. I have been in the healthcare industry for years and am guilty of not having a PCP. I had never really thought about the “relationship” aspect of a physician and why it would be beneficial to have someone engaged in my care that has seen me over a period of years rather than a quick trip in when I am not feeling well. Technology continues to change how we interact and socialize with others. It will be interesting to see how the doctor – patient connections morph as technology continues to be more readily available and acceptable in new areas.

All great points Dr. Jayne. Agreed, very tone deaf of Topol to claim AI is going to make healthcare human again.

I am very fortunate that I have long had concierge healthcare which has really helped me manage my health. I’ve had only 2 PCP’s for over 20 years and these guys know their stuff. I can always get in to see one of the docs as needed. Now, I know this is not the usual arrangement for most people, even those in healthcare IT. I have a lot of friends and acquaintences that use urgent care as their PCP so I know what you’re writing about is true. As a patient you have to be committed to good healthcare. Having a good insurance plan is vital for this. Most people here at the office purchase the least costly insurance plan available while I have the opposite philosophy. This is a world of “you get what you pay for” so if you want good healthcare, tick the PPO box. Also, watch your diet and weight, exercise, and get a physical every year. It ain’t that hard unless you make it that way. In other words, the patients who walk into urgent care and come out with a life threatening illness, have some responsibility.

As a CIO I’ve led the implementation of a number of EHRs in my career. I’ve always been embarrassed by the poor design of these systems, particularly in how they shifted the burden of documentation onto the shoulders of the highest paid workers in the work flow. I think through the influence of Leapfrog and the Fed’s incentives, we took an inefficient manual documentation process and made it worse by inflicting an “automated” clone on our physicians and nurses. All in the name of “patient safety” improvements that remain unproven.

No-one took the time to redesign the health care process first and develop roles and tasks that automation could efficiently support. A quick read of the Toyota Production System’s approach to adopting new technology shows how backward EHR adoption has been.

We do have great examples in health care where automation was handled properly. Voice recognition reduced radiology turn around times to minutes from days. Lab automation and electronic communication linked robotic testing results to the medical record with near instantaneous availability. Bedside MARs measurably improved patient safety. But when it came time to do the big one we dropped the ball.