Cant you sue the F&B company for fraud if they said they paid you money but never did?

Readers Write 4/25/12

Submit your article of up to 500 words in length, subject to editing for clarity and brevity (please note: I run only original articles that have not appeared on any Web site or in any publication and I can’t use anything that looks like a commercial pitch). I’ll use a phony name for you unless you tell me otherwise. Thanks for sharing!

CDS by the Numbers: Three Useful Frameworks for Developing Clinical Decision Support Applications

By Lincoln Farnum

Clinical decision support, or CDS, is many things to many people. Ask any 10 healthcare providers what clinical decision support is and you’ll very likely get 10 (or maybe 20) different answers, all good ones. The answers are also likely to be tinged with some degree of frustration and mistrust.

CDS as a discipline stems from the original promise of computers developing artificial intelligence — actually practicing medicine, making diagnoses, and managing patient care. Obviously these early expectations have not yet been fully realized. Today, our understanding places computers in medicine into more supportive roles.

In practice today, one commonly seen CDS application is related to medication ordering — alerting for allergies; duplicate orders and therapeutic overlaps; and drug-drug and drug-food interactions. These applications have no doubt saved human lives and resources, but often do so at a high cost to prescribers in the form of confusing messages and alert fatigue from poorly designed or executed rules.

Also, ethical concerns can affect users’ experiences with CDS. Concerns that technology-driven decision making will affect the doctor-patient relationship or that it might fail to take into account the patient’s values, or produce a cumulative de-skilling effect on physician training have all been commonly cited. There are also frequent liability concerns relating to prescribers accepting erroneous advice from a computer. It’s the fallout from these common but very reasonable apprehensions that we as consultants must try to manage on a daily basis.

Designing effective CDS is as much art as science, and it’s a quite a bit of both. Detractors of clinical decision support enthusiastically point to the occasional bad examples, but are quite often not even aware of the good ones. They seldom see “good” CDS — in part because it’s so hard to do, but also because good CDS is often invisible. CDS applications are, at their best, an unseen hand gently guiding patient care and clinical decision making.

There exist today three common frameworks for designing effective CDS: the Three Pillars of Effective Clinical Decision Support, the Five Rights of CDS, and the Ten Commandments of CDS.

Let’s begin with discussing the Three Pillars.

The Three Pillars

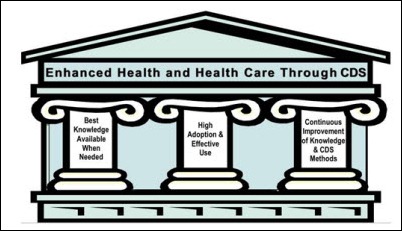

Osherhoff, et al, in “A Roadmap for National Action on Clinical Decision Support,” uses an image of three pillars supporting effective CDS. They are represented in the image below:

Pillar 1: Best Knowledge Available When Needed

- Represent clinical knowledge and CDS interventions in standardized formats (both human and machine-interpretable) so that a variety of knowledge developers can produce this information in a way that knowledge users can readily understand, assess, and apply it.

- Collect, organize, and distribute clinical knowledge and CDS interventions in one or more services from which users can readily find the specific material they need and incorporate it into their own information systems and processes.

Pillar 2: High Adoption and Effective Use

- Address policy / legal / financial barriers and create additional support and enablers for widespread CDS adoption and deployment.

- Improve clinical adoption and usage of CDS interventions by helping clinical knowledge and information system producers and implementers design CDS systems that are easy to deploy and use, and by identifying and disseminating best practices for CDS deployment.

Pillar 3: Continuous Improvement of Knowledge and CDS Methods

- Assess and refine the national experience with CDS by systematically capturing, organizing, and examining existing deployments. Share lessons learned and use them to continually enhance implementation best practices.

- Advance care-guiding knowledge by fully leveraging the data available in interoperable EHRs to enhance clinical knowledge and improve health management.

The Five Rights

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has published a CDS Toolkit in which safe and effective medication management is supported by the use of CDS, though these concepts can easily be extrapolated to health care in general. The Five Rights of Effective CDS — not to be confused with the Five Rights of Medication Administration — proposes that we can achieve CDS-supported improvements in desired healthcare outcomes if we communicate:

- The right information. Evidence-based, suitable to guide action, pertinent to the circumstance.

- To the right person. Considering all members of the care team, including clinicians, patients, and their caretakers.

- In the right CDS intervention format. Such as an alert, order set, or reference information to answer a clinical question.

- Through the right channel. For example, a clinical information system (CIS) such as an electronic medical record (EMR), personal health record (PHR), or a more general channel such as the Internet or a mobile device.

- At the right time in workflow. For example, at time of decision, action, or need.

The Ten Commandments

Finally, David Bates, et al in JAMIA published “Ten Commandments for Effective Clinical Decision Support: Making the Practice of Evidence-based Medicine a Reality,” in which he modestly proposes the following ten commandments for CDS:

- Speed is everything. Even if the decision support is wonderful, if it takes too long to appear, it will be useless.

- Anticipate information needs and deliver in real time. CDS must be presented at the moment the user needs it.

- Fit into the users’ workflow. Users won’t go looking for CDS — it needs to be in their workflow.

- Little things can make a big difference. Small changes in delivery can have an oversized effect in outcomes.

- Recognize that physicians will strongly resist stopping. Don’t bring clinicians to a dead end when making suggestions.

- Changing direction is easier than stopping. Propose alternatives when advising against something.

- Simple interventions work best. Complex and multi-paged guidelines will not be readily accepted.

- Ask for additional information only when you really need it. Try to obtain all necessary information passively. Ask for additional information only if it is absolutely required.

- Monitor impact, get feedback, and respond. Verify that interventions are producing the desired outcomes and communicate with your customer base.

- Manage and maintain your knowledge-based systems. Suggestions based on outdated information are dangerous and worse than no suggestions at all.

Obviously, this is a very high level overview of these frameworks. The below links will provide more information and context. The simple take-home lesson is that effective CDS isn’t easy and even good CDS isn’t always accepted or performs as its developers intend. The development and deployment of clinical decision support should be undertaken with an understanding of the challenges and recommendations for best practices, and with the strong cooperation of and input from the user community.

A Roadmap for National Action on Clinical Decision Support, Jerome A. Osheroff, MD, et al.

AHRQ, Approaching Clinical Decision Support in Medication Management

Ten Commandments for Effective Clinical Decision Support: Making the Practice of Evidence-based Medicine a Reality, David W. Bates, MD, MSc, et al.

Lincoln Farnum MMI, RRT-NPS, CPHIMS is a senior consultant with Vitalize Consulting Solutions, an SAIC Company and a graduate teaching assistant in the Master of Science in Medical Informatics program at Northwestern University.

I’m a Believer in Diagnostic Decision Support

By Scott W. Tongen, MD

When I read a vendor’s brochure about diagnostic decision support software that mirrors how medical students and physicians in training are taught to diagnose patients, I had an epiphany. My peers and I today are not diagnosing patients the way we were instructed in medical school and residency. As a result, we — and our patients — pay a heavy price.

As students and residents, we were asked to provide a list of all possible diagnoses based on patient’s symptoms, medical tests, accumulated medical knowledge, and other information. Next, we would use the data at our disposal to eliminate diagnoses that did not fit until we were left with one diagnosis.

However, advances in imaging software and electronic health records, revenue pressures, and crushing time demands had led us to stop using that “differential diagnosis” methodology on a daily basis, leading to misdiagnoses or missed diagnoses.

None of us likes to admit our mistakes and fallibilities when we’ve misdiagnosed or missed a diagnosis, but it happens: 40,000 to 80,000 patients die annually due to misdiagnosis, according to a 2009 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I believe a major reason for an inaccurate or incomplete misdiagnosis is due largely in part to the increased use of powerful EHR systems. Those systems are deemed so efficient now that they lull highly skilled and trained professionals into a false sense of security. Too many physicians rely on electronic alerts and images to help them solve the mystery of a patient’s illness, forgetting that technology can be a poor or terrific tool, depending on whether it is used correctly.

Also, doctors and hospitals do not realize that EHRs are not sold “out of the box” with diagnostic decision support that generate potential diagnoses and flag high-risk “Don’t Miss” diagnoses when patient’s symptoms and vital signs are entered into the application. When clinicians do not know what they do not know or are not thinking about a possible diagnosis, they certainly will miss it.

Another reason for misdiagnoses and missed diagnoses is physicians’ busy schedules, as continual reimbursement cuts are forcing them to squeeze in more patients. This, combined with other demands competing for their time, make it impossible for doctors to remember all pertinent details that could potentially explain a patient’s problem, much less keep up with the massive explosion of peer-reviewed studies and medical discoveries published in numerous medical journals.

All those thoughts flashed across my mind as I read the brochure, which ultimately led to my convincing administrators to fund and offer the tool to our physicians. Diagnostic decision support software can help doctors address those problems while minimizing misdiagnoses that harm or kill patients.

For that reason, every physician and hospital in the country should implement diagnostic decision support software that highlights and enables them to access relevant information about potential diagnoses. They will find the tool extremely valuable, particularly when diagnosing difficult as well as rare cases. A useful objective review of these tools was published recently, “Differential Diagnosis Generators: an Evaluation of Currently Available Computer Programs” by William Bond, MD, MS et al from the Lehigh Valley Health Network.

To be clear, I am not proclaiming diagnostic software needs to emulate a physician’s thinking. What I am advocating is that doctors should use it to bring up diagnoses they otherwise would not have considered or remembered. The tool will more than pay for itself if it prevents a single fatality or serious misdiagnosis. More importantly, it will enhance quality and safety of care.

At the time this article was written, Scott W. Tongen, MD was medical director of clinical documentation, compliance, and quality at United Hospital, part of Allina Hospitals & Clinics in Minneapolis. He has since joined Vitalize Consulting Solutions, an SAIC Company as medical director.

Nice overview of key CDS frameworks Lincoln.

FYI, the CDS Five Rights framework was first described in the 2009 HIMSS guidebook on applying CDS to medication use and outcomes – the AHRQ link you cited is an excerpt from that book.

Further details on applying the CDS Five Rights framework to improving outcomes are provided in the 2012 update to the ‘classic’ 2005 CDS guidebook.

Information about both these guidebooks is at http://www.himss.org/cdsguide.

>>> “As students and residents, we were asked to provide a list of all possible diagnoses based on patient’s symptoms, medical tests, accumulated medical knowledge, and other information. Next, we would use the data at our disposal to eliminate diagnoses that did not fit until we were left with one diagnosis.

However, advances in imaging software and electronic health records, revenue pressures, and crushing time demands had led us to stop using that “differential diagnosis” methodology on a daily basis, leading to misdiagnoses or missed diagnoses.”

When I have a difficult case, I go online to use free resources on the ‘net, s.a. the Medscape’s eMedicine online textbook. I really don’t think or want my EMR/EHR to do this for me for multi-thousands of dollars. An EMR is a great tool to follow patients- and that’s all. I have yet to see a well-randomized, prospective, unbiased study showing that the EHR decreases errors (and some studies show may actually increase them), decreases cost (and most likely increases costs by $60000/yr as per my and other editorials), and increases “quality.”

>>> “For that reason, every physician and hospital in the country should implement diagnostic decision support software that highlights and enables them to access relevant information about potential diagnoses. They will find the tool extremely valuable, particularly when diagnosing difficult as well as rare cases. ”

It’s like religion- some may actually like artificial decision support. Call me an EHR atheist- all I ask is that big government and the insurance industry mandates keep out of my office.

Sincerely,

Dr. Borges

Agreed, nice summary. But to help further this debate, may I ask if we are blending a couple of concepts here? I’m afraid that this is might cause confusion.

When David Bates and others discussed CDS or Clinical Decision Support, I pictured alerts and reminders at the point of service such as drug interactions (as Lincoln mentioned) or “patient is due” alerts. Diabetic overdue for HgbA1c. COPD patient needs a pneumovax. Specific, high value, shown to improve clinical outcome and patient well being.

Diagnostic decision support is another animal, isn’t it? Accumulating a series of symptoms that may suggest a list of diagnoses, each with a certain likelihood? And perhaps also what test would help distinguish one from another?

In either case, there is the problem of information overload, alert fatigue and confusion from vague advice. Who hasn’t had a drug interaction alert that was mistakenly triggered by a minor ingredient (e.g. yellow dye) that is present in two completely unrelated drugs. Talk about alert fatigue!

For CDS, I believe that the scholarly discussion of the future needs to be “how can researchers and policymakers help vendors of CDS technology know where to draw the line.” Today the safety net of CDS is cast widely, maybe too widely. Let’s demand that high quality evidence of improved health and safety be the expectation, and information overload a marker of poor design.

Thanks very much for your clarification and information Dr. Osheroff!

…we’re using the new edition of ‘Improving Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support: An Implementer’s Guide’ in the CDS course at Northwestern I’m currently assisting with. Lot of excellent new content!

Thanks again!

Lincoln