Shivdev (Shiv) Rao, MD is co-founder and CEO of Abridge of Pittsburgh, PA.

Tell me about yourself and the company.

I used to be a corporate investor for a large hospital system, UPMC. A lot of my investments were focused on AI technology. We put a lot of capital into Carnegie Mellon University and started a machine learning and health program there. A lot of the founding DNA for Abridge comes from Carnegie Mellon, and a lifetime ago, I went to Carnegie Mellon myself. In the middle, I became a practicing cardiologist.

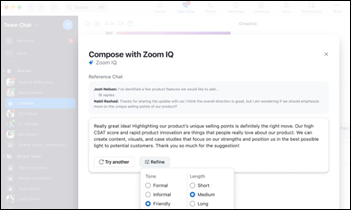

At Abridge, we’re building technology that can be a part of all of the conversations that I as a clinician have with patients, whether they are over the phone or even over telemedicine. The technology, in real time, creates clinical notes for me that can help with clinical care team communication. It also structures information for me, that can help with billing oriented workflows. And Abridge can also help my patients as an extension of my best intention, helping them better understand and follow through on everything we talked about, even when they’re not in front of me. Our goal is to unburden clinicians from clerical work and help them and their patients better understand and follow through on the healthcare plans that will improve experiences, and economics immediately, and also improve outcomes over time.

How do you differentiate Abridge from Nuance DAX?

This space is ripe with opportunity. Between Abridge and other companies in this space, we are pointed in different directions, which will lead us to very different destinations. Abridge is based on this idea that healthcare is really about people. Upstream of all the diagnostics and therapeutics in healthcare, the most important people in healthcare – providers and their patients – are having conversations. Being able to structure and summarize conversations in real time without any humans in the loop, and then being able to structure that data, means that we can start to unburden clinicians from the three customers that they’re serving every time they see a patient.

First and foremost, there’s the patient. We know that’s the most important. But then there are colleagues on the care team for whom they need to create a different kind of clinical artifact. Then there is everyone in revenue cycle, everyone on the coding and billing side, that they also need to be thinking about. We’ve taken the tack of building technology that doesn’t have any humans in the loop, that we can democratize across every single doctor and nurse out there, that doesn’t anchor on scribing per se.

That’s a word that that company, and other companies, might leverage increasingly if they’re using AI to basically power more efficient scribing. But that’s not really our positioning. What we’re building is more of a co-pilot that can be a part of all of these conversations that can create these summaries in real-time to help everyone better understand and follow through. As a tech company, our mantra is cheaper, better, faster.

It would seem useful for the provider to set aside 30 seconds at the end of the visit to intentionally dictate a summary that could benefit that provider, the patient, and anyone who has to interpret the chart downstream.

That is absolutely one of the key differentiators between Abridge and any other company in this space. While we are physician driven by me, we are also patient centered, and we are AI powered. We think that’s the key triad for clinician facing AI solutions. For everything that we are building from a product perspective, the person who’s going to benefit the most should be the patient. But we are AI powered. This is all about technology. We can partner with and help services companies, but what our offering is all about is being able to be in the workflow incredibly fast. We want to be able to create value for everyone involved, and that starts with patients and their clinicians.

When we started this company, we knew the kind of technology that we wanted to point at this challenge. We knew it was based on this new type of machine learning model called a transformer. One of the key papers about transformers came out in December 2017, and we started the company in March 2018. But from a mission perspective, we also knew that there’s such an opportunity to help patients better understand and follow through. Given the way healthcare is evolving, given all the increasing momentum around providers taking risk and payviders becoming a bigger phenomenon, being able to not just put the patient at the center of workflows, but actually demonstrate and measure how you can help them better understand, follow through, adhere to their care plan, and actually improve outcomes even over time, will be a game-changer in healthcare.

I started seeing patients eight or nine years ago as an attending after fellowship. I would pick up the phone after a procedure, like a Holter monitor or an echocardiogram, and I would start dictating the procedure report. People in the basement of the hospital were actively, synchronously on the line listening and typing, and then that report would end up in the medical record. In relatively short order, it evolved into this new world where I would pick up the phone and essentially do the same thing, but it would get recorded, and someone later on would listen to the whole thing and put the report in the medical record. Then it evolved in very short order to this other world, where there was a technology in the middle that was transcribing everything that I said into the phone and calling out where the speech recognition technology was less confident. The humans who were listening later could just focus on those words, correct those words, and get them back in the medical record. That created this huge efficiency.

But the final form of dictation of monologues was a product where I could pick up a Dictaphone and just dictate and see the words in real time show up in my medical record the way it does on our phones these days. I could correct things on the fly.

They say that history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. We think that this space of dialogues, not dictations, will follow a similar pattern. In this space, the first model was scribes or extenders in the corner of the room, writing the note in real time as I have an encounter with my patient.

For some companies, that evolved to humans who connect and listen in real time to the conversations through audio or video. More recently, we see companies record conversations for humans to listen to later on and be able to write the note. Those companies are trying to build technology that can help them be more efficient in listening to the conversation, writing the note, and getting it back into the medical record.

This is a key point of differentiation for us, because at Abridge, we are generating a note draft along with structured data that we integrate into the medical record in real time. We are not comparing ourselves against a human and saying that AI is going to be better than all the things a human can do in the workflow, especially at the clinician level in relation to a doctor or a nurse and how they might want to document or think about, especially the decisions that they need to make.

Instead, what we comp against is technology that in real time is listening to the conversation, generating a summary, structuring data, and putting it into all the different slots of the medical records. Your workflow is that much more frictionless, but we still require the clinician end user to be in the loop and work with the AI-generated output. It’s apples versus oranges compared to an AI-powered scribe model, but we think it also follows a similar pattern of evolution to what we’ve already seen happen in the dictation space.

ChatGPT has sucked up a lot of the technology air in the room in its few weeks of public availability. What advancements and disappointments do you think we will see?

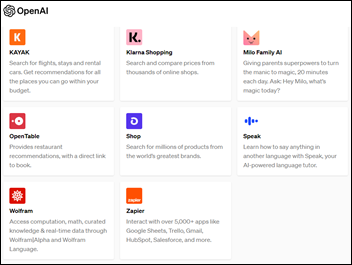

In terms of advancements, there’s no question that there’s an ability to leverage this kind of technology, these sorts of what they call foundation models or large language models in healthcare technologies. There’s no question that there is incredible value. At the same time, we are seeing in real time that t’s pretty easy to create a flashy demo with these technologies, but that doesn’t mean that that demo can translate into actual enterprise workflows inside of hospitals, inside of clinics, that have a different kind of standard in terms of reliability, credibility, transparency, and auditability. Those are all the different dimensions of trust, which is a requirement, which is table stakes.

Everyone is going to find a way to leverage this technology in some part of their stack, their modules, if you will. That doesn’t make an AI company, though. There will be also be AI-native companies like Abridge, and an AI-native company is not going to leverage one of those large language models in a superficial way. It’s not going to be a straightforward query or prompt. As an AI-native company, Abridge builds technology underneath those models and beside those models. We fine tune those models, we build technology on top of them, and we integrate them deeply into workflows. That’s where the magic actually ends up happening.

There’s a joke that every company in the United States is a healthcare company, because every company is offering healthcare benefits to their employees. There’s an interesting phenomenon now where every company will be able to say on some level that they are an AI company if they are leveraging an API like GPT. That’s not an AI-native company. AI-native companies will be able to commoditize different solutions in their space and drive value up the stack to new ideas. Those are the companies that are going to have to have the talent, the expertise, and the data to actually build their own models, which can coexist with the large commercial models that are out there.

Will technology companies see the danger in trying to promote their AI products as replacing the physician’s judgment?

It’s definitely a risk. There’s no question about it. The framework that makes the most sense is that AI can assist, augment, and automate. How you point any one of those — assist, augment, automate — frames at solutions is the key.

What does that heuristic look like? Imagine a two-by-two, where the risk, the consequences of making a bad decision, is on the X axis. The volume of decisions is on the Y axis. All the decisions on that half of the two-by-two that involve a high consequence for any given decision going sideways deserves a frame thinking about AI as something that can be assistive or that could augment, but not something that can automate anytime soon.

Whereas where there are low consequences of decisions, and where there’s a lot of volume of those low consequences of decisions happening as well, that’s low-hanging fruit for this kind of technology. When you think about the healthcare workflows inside of clinics, it’s probably not at the point of care that you’re necessarily automating doctors or nurses and the decision-making that they’re doing, the creativity that they are having to bring to the table. It’s probably way more likely that it’s in the back of the office in the rev cycle, authorizations, coding, and all those workflows where there isn’t the same sort of stakes from an outcome perspective.

How could technology in general help healthcare scale to address the clinician shortage and their uneven geographic distribution?

That’s part and parcel with the mission of Abridge. When we think about the current climate, healthcare systems are underwater. We hear from the president of UPMC on the physician services side that staffing is the number one concern for hospital CEOs, because nearly two-thirds of doctors are experiencing at least one symptom of burnout. We keep seeing headlines around hospitals actually closing departments or ending services. When you think about hospital margins, they are as slim as ever before.The cost of labor is a 19% expense growth per discharge. The drivers here are absolutely putting so much pressure on the system at large to figure out how they can increase productivity from a dwindling labor force, and at the same time, actually have that labor force be smiling all the while. How can they bring joy back to that labor force in such a way that they’ll actually end up seeing more patients? It’s a very, very tricky line to walk and pull off.

That’s where technologies like AI can come in, and generative AI specifically. The way that we leverage AI at Abridge is that this is technology that’s getting out of the way. You can bring it into your conversations. This is technology that can scale because it’s all technology, it’s real time, and it’s flexible enough that we have an API that can integrate with telemedicine, for example, or call center conversations. Not just doctors, but nurses, PAs, medical students, and trainees. Everybody can benefit from this technology. That will lead to people having better conversations with their patients, being more present, and patients having better experiences. In the case of Abridge, since we also have an offering on the patient side, we want to be able to demonstrate that it is improving understanding, and better follow through. The aspiration is to demonstrate better outcomes.

Financial markets are down and health systems are struggling with their bottom lines. How will the market look in the next 3-4 years and how do you position the company?

The idea more than anything is to leverage technology to rise to the moment of this public health crisis. In terms of strategy, there’s a great quote that startups get disruption when they get distribution faster than incumbents get innovation. It summarizes all the Clayton Christensen books. The name of the game from a strategy perspective is finding a way to create as much impact as possible. That’s always the promise of technology, that it can scale infinitely and that we can distribute this at a price point that all the healthcare systems, all the clinics can actually afford. Not just for their doctors, but their entire staff over time. That that aspect of our strategy is crystal clear, that we have to be cheaper, better, faster. We have to leverage technology and all of the affordances that come with it to get this out there at this moment in time, right now in 2023 when the need has never been greater.

In the moment right now that we are in, it feels like we have two huge waves that are starting to intersect. At Abridge, we are riding both of them. One of those waves has to do with this public health crisis, clinicians burning out, margins remaining slim, and this challenge around us as a society of the healthcare system not having enough clinicians to actually deliver the care that everybody needs, that our communities require right now. How are we going to respond?

In parallel, we have this other huge wave around generative AI, and all of us as a society starting to understand that this is a solution, there is a lot of magic in this. How do we find a way to get them to intersect to point generative AI at this public health crisis and create value?

Paradoxically, generative AI can be just the thing to highlight the humanity in healthcare, to help people be more present and focus more on each other. That more than anything is going to improve experiences, outcomes, and start to solve this challenge that healthcare systems are dealing with. At Abridge, that’s our mission, that’s what we’re all about, that’s what we’re focused on. We have been super excited to be able to partner with large healthcare systems, not just UPMC, but we recently announced University of Kansas Health System, where over 1,500 clinicians are going to be able to leverage our technology in real time in a very deeply integrated way with their healthcare electronic medical record system. We are excited to be able to demonstrate that we can scale this across systems and across the entire United States over time in a very short order.

Comments Off on HIStalk Interviews Shivdev Rao, MD, CEO, Abridge

![image[6] image[6]](https://histalk2.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/image6_thumb.png)

This is a great point—many discussions about patient wait times still focus on staffing or technology, while the real issue…