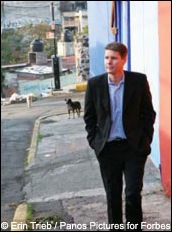

John Gomez is executive vice president and chief technology strategy officer of Eclipsys.

The HIStalk reader who suggested I interview you said that you are the Steve Jobs of healthcare IT – the industry’s leader, visionary, and celebrity. Do you see yourself in that way?

No, I don’t see myself in that way. It’s kind of funny, but no, I do not see myself in that way. I guess it should be flattering, but I don’t think I see myself as the Steve Jobs of healthcare.

His reasoning was that the areas you’ve worked in for Eclipsys have thrived, that customers follow what you do, and that employees get your message. Is it good for the company for you to have such a strong customer following and loyalty within the company?

It depends. I’d have to look at the mix of clients that we’re talking about, but I think it’s good. I think it’s great that clients love the message that I deliver, but that message is put together with all of my peers, the teams that I work with. I don’t certainly believe that it’s a one-man show.

I think it’s part and parcel for the company itself, and the company is delivering the message. If I’m the instrument or the megaphone for that, then I’m just happy that the message is resonating and that the people that are receiving the message actually are resonating with what’s being said.

But I don’t certainly think that it’s just me. It’s just the culmination of everything that’s going on around me, and the people that I’m fortunate enough to surround myself with.

Company executive turnover has made you the one constant over the past several years, the continuity between one group of executives and the next. Is there anything that you have to be cognizant of or anything you do differently knowing that you’re the continuity in the customer’s eye?

I don’t know. Although I don’t consciously sit there and go, “Ah, I think I need to make sure this is preserved or not.” I think for as much change as there’s been — and I certainly think all the changes happened for the right reasons — I kind of view it and when I talk to clients about it is that these are evolutionary changes and they’re, in my view, not disruptive.

But that said, I think the one thing that is important, at least from my standpoint — and whether this is me actively doing it or just part of the fact that it’s the way the company’s been operating — is that the message has been consistent. At least for the six years that I’ve been here and through any of the management changes, the messages have continued to be consistent. Now, more than ever, I think that message is going to continue to propel forward. The strategies and the views that we’ve been delivering to clients, that’s something that has prolonged regardless of any changes in the management.

Phil’s been with the company for six months. What changes has he made?

I think Phil is an extremely interesting person as a CEO. He has a strong technical background. He has a very strong financial sales and marketing background. I think he’s able to bring together the different perspectives. I think one of the things he’s been able to do is truly create a cohesiveness amongst the executive team, which is translating into everything we do across the company.

I think more than ever, that we’ve got a very strong synergy between our service and support, development, marketing, and sales organizations. He is also holding, very strongly, more so than ever before, people accountable through the commitments we make to our clients.

Overall, I’m actually loving working with the guy. I’m not brown-nosing if he reads this answer or not. I just think that he’s actually doing a very strong, very good job. Overall, he’s just brought a whole new set of disciplines to the company. I think it’s the right change at the right time, bringing him on board.

As a technology guy who’s worked outside of healthcare, what do you think about an industry that’s dominated by healthcare-only development tools, like MUMPS?

I think it’s time for a change, but I think not just because of the technology around MUMPS. We’ve got products at Eclipsys that are built on MUMPS, although we’re moving off those. I think that there’s a lot of opportunity in healthcare. I think the way that things are done from a technology perspective, we need the change.

I can say it’s kind of a sad situation that healthcare is so far behind the rest of the world from a technology perspective. There’s very little innovation in healthcare around pure technology. There’s a lot around the modalities, but if you think about it, the core essence of innovation doesn’t come from healthcare. That’s really sad because this is the one industry that really affects peoples’ lives every day.

One of the things I tell my engineers all the time is this is the only job you will ever have, even if you work for like a 911 system or for the government, that your code could kill someone. It seems really interesting to me that we have that responsibility in our hands, but yet overall as an industry, very, very little innovation comes from this industry. To me, it’s just upsetting, that kind of state of affairs for us.

Would you say that the limitations of today’s systems are because of their technology, or because of their design? Or, because it’s just the inertia of having to go back and start over?

I think it’s all three and more. I think that we have a lot of hospitals that are comfortable with the technologies that they’ve put in place. It’s not just hospitals. I think it goes across everything from physicians to long-term healthcare facilities. Across the spectrum of healthcare, they’ve become either comfortable or they resist it because of the fear of adopting technology and what that may mean to them in the learning curve.

Which goes back to innovation, it shouldn’t be that hard to implement and embrace these systems and put them to practical use. I think the technologies themselves create very, very challenging barriers to entry. For some cases they’re very old, twenty-, thirty-year-old technologies like the MUMPS stuff.

I think we also don’t pay attention to paradigm shifts. Right now we’re seeing paradigm shifts in other industries, like cloud computing. We’re seeing things scaled down and scaled up to either mobile platforms or large-scale, interactive platform kind of environments. We don’t embrace that. We’re not leading that, yet it can make a tremendous difference to healthcare.

Interoperability is a huge one wherethe way that this industry’s worked, has been not embracing the ability to exchange or interoperate between systems. We’ve been kind of proprietary. I think that also creates a challenge and a barrier for hospitals to move.

I also think that there’s just kind of, at least from a technology perspective — and I’m first and foremost to talk about Eclipsys, but I think we’re fortunate that we have great people — I don’t know if the industry is attracting great technologists. That also creates a challenge through this inertia of innovation.

But if it’s a perfect market, customers get what they ask for; assuming that someone would step in and give it to them if the current vendors didn’t. Are hospital customers too easy on their vendors?

That’s an interesting question. I think hospitals could push vendors much, much harder to drive the evolution of technology. I think there’s an inherent responsibility that when you work in a healthcare facility or a healthcare information technology vendor, that your responsibility is at the end of the day, to try to get the best quality care for the patients that are using that technology. If you’re not driving the vendors to innovate and evolve their product lines and embrace new technologies, then I think the hospitals are being too easy.

The studies that have come out in the last couple of weeks are suggesting that systems are not meeting expectations for improved quality and reduced cost. What should hospital software vendors do if that’s true?

If it’s true, it probably goes down to a lot of the cryptic things that you just see in a lot of the vendor systems. They’re difficult to implement, they’re difficult to configure, it’s difficult to maintain online. Quality is not what people expected it to be. The usability is, in some cases, ten-, fifteen-year-old paradigms. Those kind of things need to change, right?

The vendors need to be in a position where they’re affording people solutions that are usable, and if they’re usable, I think you can drive adoption. When you drive adoption and you can apply technology to patient care, you will translate it to better outcomes. I mean, we’ve just touched the tip of the iceberg in terms of using things like analytics or predictive informatics or diagnostic decision support instead of clinical decision support.

If you look at the Gartner Scale, there are very few vendors that are Generation 3. I think there’s only three. I could be wrong on this, but I think it’s us, and I’m thinking Cerner. Generation 4 is what vendors should be striving for. HIMSS Level 6 is just starting to become something that most vendors are able to do, and really, they should be driving for HIMSS Level 7. The hospitals should be using and applying those tests and saying, “This is where we want to be. This is our vision, and we’re just not going to buy from anybody that doesn’t allow us or enable us to get there.”

You mention data; and everybody wants to use data, but not be the one to have to create it. Eclipsys is pretty well acknowledged as the CPOE expert. Is that paradigm valid, or do you see anything changing that makes that somewhat of a dated concept itself — the idea that physicians need to type into a system to be able to reap these other benefits or provide someone else some benefits?

I think that yes, things have to get easier for physicians to want to enter the data or provide the data. I think that’s a great way to paraphrase it. Until we lower the bar or the difficulty of the user of the system to enter that data, then we’re not going to have the richness there. We’re not going to have the full picture that allows us to treat patients effectively.

What’s interesting is we’re kind of in a situation where if we can lower the bar, get people to provide the data in easier and easier ways, it actually helps all of us long term. Not just as vendors or hospitals, but even our own interest.

At some point, we don’t just want to look at episodic care, we want to look at womb-to-tomb kind of care and long-term care. The more data we have, the better outcome we’re going to have individually. Then when we go to a doctor or we go to a hospital we want that level of care, yet we’re not, in most cases, doing anything to enable it.

From an Eclipsys standpoint, we are doing a lot to try and lower that bar. There are technologies we’re looking at and changes to the way that we’re collecting data and allowing providers to be immersed with an experience that hopefully will start making things much easier to do. I appreciate you saying we’re kind of the experts in CPOE, but I don’t think we can stop. We have to keep pushing things further.

When will we see what kinds of things that you’re looking at in technology?

From an Eclipsys standpoint, not to be a teaser or things like that, there are a variety of things that we announced at our Eclipsys User Network around visual workflow and our new solutions platform and where we’re headed with that.

But in terms of the UI, we’re doing a lot to move our UI forward. Now one of the challenges for any vendor is that you don’t want to create disruptive change because that becomes very costly and becomes, in and of itself, a barrier to the healthcare institutes. What we’re trying to do is take an evolutionary approach to our UIs and incorporating usability as we go. But some of the things you’ll see in our next release are that the UI adjusts to you, it learns from you depending on where you are in the system.

One of the other things we’re doing is working on a concept of Workbenches, which create an immersive experience for a particular type of provider. So if you’re a nurse, the assistant is tailored to you as a nurse and reflects the support of your workflows. If you’re a physician, it supports your specific type of workflows.

The other thing we’ve been working on for a long time is thinking through how we can apply gaming concepts to the UI. In fact, one of the key things in terms of getting data or responding to data that involves a patient is being able to present information in the UI in a way that doesn’t overwhelm the practitioner. So we’ve been working very hard on providing the right information at the right time for whatever that practitioner may be doing in terms of their scope of the workflow.

Those kinds of changes have to be very specific. We hope you’ll start seeing some of those things come to market in the Q1 timeframe, and then we also have some things slated for the Q3 timeframe in terms of uplifts to usability and things like that.

Wall Street has typically punished publicly traded companies that rewrite. Is the technology there to allow those sorts of changes without really scrapping the database and the underlying architecture?

We started back in what, 3.5, which was about 2004, and we’re now coming to market in Q1 with our 5.5 release for our clinical solutions. We’ve been evolutionary all along, and so we’ve introduced things like ObjectsPlus, aligning third-parties that develop applets. We opened up our MLM library to allow people to develop these kinds of self-contained macros. We’re building on top of that. Our platform, going forward, we’ll continue to move those things forward.

One of the big areas that we’re investing in now is opening up the APIs so that they’ll be a service-oriented architecture. We very, very have seriously been looking at cloud computing and seeing how we can invoke that and provide kind of a healthcare information technology as a service.

None of these are disruptive. I mean, we’ve had a great legacy of our upgrades just being in-place upgrades and not requiring you to do schemas or lose the work you’ve done or redevelop the add-ins that our third-parties or our clients build. We want to just keep going forward, and the big thing we’re trying to do is open up the platform, allow for third-party innovation. Hopefully, we’ll even have competitors build on top of our platform.

We’re charting a course where none of that will occur with disruptive changes. I think there’s a time and place for disruption. I don’t think this industry is, right now, ready for disruption as they’re trying to get their arms around everything going on with the government trends and outcomes and everything else.

Some people would say that a lot of the reasons the same old systems keep selling is that IT departments want to avoid risk and perceive that that’s less risky. Do you think that that whole concept of extensibility versus just buying everything from a single vendor, even if it’s not very good, is going to be a message that will resonate with the right people who make hospital decisions?

I think you’re starting to see both. I think you’re starting to see that kind of the larger hospital systems are taking risk in saying, “Look, we’re going to change and swap out systems.” They’re starting in probably the departmentals because they’re seeing the benefits of fully integrated applications.

We’re moving down the path very strong. We have a fully integrated platform. That said, though, if you’re going to have innovation and you’re going to really drive vendors to continue evolving, I think it’s really rare where you can have one vendor that is going to continually innovate as such a pace that it will allow you to meet the needs of the hospitals in terms of patient care over the long-term.

You know Apple — you mentioned Apple at the beginning of the talk — Apple’s a very unique situation. They get innovation right and they’ve been very good and strong at what they do. I think it’s hard to replicate Apple’s success, so the answer to that is have an open platform.

Sure, you can go with integrated; you can go with single-vendor, but never tie yourself into a position where you can’t innovate on top of the platform that you’ve chosen. That openness should allow you to bring in third parties, to build your own applications as the institutions, but protect you from not being locked into a single vendor solution.

The company invested in EPSi and practice management. Are those key to the single strategy, or is that just a way to broaden the front that you put out to customers?

It’s kind of both. From one standpoint, we’re working right now to natively integrate those offerings, but the way we’re doing native integration is that everything can also stand alone.

For instance, EPSi will be integrated with our core solutions platform, so it means it’ll share security and auditing and other pieces of our platform with all of our applications. If you were to buy EPSi and you didn’t own any other Eclipsys app, when you install it, it’ll lay down the core platform. If you buy another application from us, then it will use what has already been put in place. You don’t have to redefine security. You don’t have to redefine auditing or roles, or places within the hospital or anything else — cost centers or cost codes, billing codes.

But that said, if you were to just buy EPSi and you wanted to integrate a third party, you should be able to do that without having to buy anything else from Eclipsys. So, we see that. EPSi certainly pushes forward our ability to move into new market areas and integrate in places that don’t previously own Eclipsys products. We also see it as a complete offering on top of an integrated platform. That core comes from Eclipsys so, there’s a little bit of both.

Do you see any possibility that either customers or third parties will develop open source components that work with your products?

That’s a really interesting question. For us, one of the things we announce at the Eclipsys User Network was the Eclipsys App Exhange, which will roll out in Q1. The App Exchange will be an opportunity for not only clients, but for third parties to actually build applets or MLMs or visual workflow add-ins and things of that nature on top of our platform.

If the third parties or the clients wish to put that into the public domain or license it specifically as open source, it’ll be their choice. We won’t regulate that. It’s very similar to the Apple Apps Store concept. We have not worked out yet whether or not we will invoke a commerce engine on top of our platform.

For now, we’re just seeing that clients can either exchange content or applets with each other, or get them from third-parties and then work out the revenue model between themselves. What we really wanted to do is be a facilitator and take the work we’ve done in the platform and now extend it out to third parties.

We’re talking to third parties now, who actually are competitors of ours, and they’re learning about what we’re doing and they’re saying, “Ah, this actually would reduce my cost of ownership because you guys are going to do all the plumbing work. Then, I could just snap on top of you.” What we’re saying to them is that’s great. We’d be happy to have you on the platform, but we may compete with you.

So far we’ve gotten feedback that people are saying, “Well, then let the games begin.” I think that kind of stuff is great for healthcare because it lowers costs, it opens things up, third parties can innovate, and hospitals aren’t tied into a single solution at any point in time. It kind of feels like it’s the right kind of place to be doing this.

Does Eclipsys have what it takes to compete for the long haul against some pretty formidable and well-funded competition like Epic and Cerner?

It would be hard for me to say no to that question, but my honest gut-level belief is yes. Think of it this way. Our clinical are considered the best in breed. One in four physician orders, I believe, in the US electronically placed is placed on an Eclipsys system. We’ve been improving steadily our KLAS rankings. Our customer satisfaction is up. So from that perspective, we’re doing all the right things.

We’ve just now announced the new Sunrise Financial Management product that comes out in early 2011. That’s our full-blown revenue cycle system with ambulatory billing and international support, fully integrated into our clinicals. Not interfaced, but true integration.

We’ve got fully object-level integrated pharmacy. We’ll very shortly have fully-integrated lab. Then on top of that, we’ve got one of the few fully-integrated clinical analytic packages, which will allow you to do data warehousing out of the box; do all your core measures and do visual query by example.

Then you’ve got the EPSi and the Premise workflow stuff on a single platform. On top of that you’ve got the visual workflow tools which will allow you to use Vizio-style diagramming to actually visually draw your workflows.

On top of that, that visual workflow tool can work with any web service in the world. It doesn’t matter whether it’s an Eclipsys web service or a third-party web service. So I look at that and I go, “Wow, that’s the breadth of the platform and we’ve got a very strong vision of where we want to go.”

We’re lowering the bar in terms of how usable the system is and allowing third parties to create an ecosystem through the Eclipsys App Exchange. I not only think we have the ability to compete with the Epics and the Cerners and whoever else may come along, I think in very short order they’ll be wondering like, “Holy crap. What have we been doing all along, and how are we going to deal with this?”

What does Epic have to do to stumble enough to let somebody else get back into the big-hospital game?

Good question. I’ve met Judy a few times. I think she’s a very, very brilliant person. She’s doing a great job at what Epic does. I think that right now, Epic’s situation is that they seem to be doing the right things, but I’m not really sure they’ve done anything hard.

I think they’ve gotten some preliminary implementations done. They’ve done some good large hospital implementations. But when you get into the real serious acute care, when you get into the real treatment of very, very sick patients; to the best of my knowledge, I don’t know if they’ve proven themselves yet. So it’ll be interesting to see where they go with that.

We’ve been doing long-term care, long-term disease management, critical care, oncology; you know, real in depth stuff for a very long time. Now we’re pushing very, very, very actively into the ambulatory market. So it’ll be interesting. I think it’ll be, through the next two to three years, a very interesting battle. I’m not sure if I, specifically, would feel comfortable saying that if Epic does these three things, they’ll stumble. But I think that there’s a short-term…

I would compare Epic to Netscape in that they were kind of an industry darling for a long time, but then when people wanted to get to the next level of the Internet and really start pushing things really hard, Netscape didn’t seem to be the answer. We’ll see if that turns out to be reality or not, but the reality is I think they’re a great company and Judy’s a great person. The people I’ve met from there are really talented people, so it’ll be an interesting competition.

The problem is they’ve taken away this window of time that’s driven by everybody’s first big clinical implementation and the HITECH possibility is there. They’re grabbing all the big customers who aren’t going to just dump them after they’ve spent $50 million. Are there going to be enough customers left to buy somebody else’s innovative product?

I’d let somebody else in the company talk to our financial sales, but from what I’m seeing, I think you will see that we continue to have strong, steady growth. The piece in terms of, are there other people left, right now there are selection processes going on that we’re beating up again. It’s actually good things.

We’ve introduced the “Speed To Value” methodology which reduces our implementation timelines by a dramatic amount and improves the quality. We’ve introduced a warranty that helps provide and drive our ability to assure that clients will get HITECH certified. I think if anything, we probably just aren’t talking up enough all the things that we are doing. But I don’t see that, “Wow, Epic’s doing all this stuff and Eclipsys isn’t.” So if anything, I think we just kind of walk a silent path and just keep doing what we’re doing. So far what we’ve been doing seems to feel and be on the right track.

Do you think offshoring of development has done as well as everybody expected?

I think we’ve learned a lot about offshoring. At this point, it’s just another office. The one thing that I think has helped us is we’re being able to bring a lot of young talent on board. That’s helped a lot with our ability to actually evolve the platform and evolve the other things that we’ve been doing.

I think that if I were to do it again, I might approach the problem differently, but I would certainly do it. I don’t think there’s anything in my mind that makes me go, “Wow, we shouldn’t have done this,” or “I would never do this again.” So far, it’s been an effective tool, and at this point in time, it’s another office for us.

We have development teams that have different geographic rotations. We’ve put the technology in place, like Cisco TelePresence and other things, to help coordinate those teams. We’ve got strong management layers in place to assure that those teams are held accountable. At this point, our offshore teams are no different than any of the other teams that we have.

Last question. What would you say the most important priorities are for the industry? Or what should they be over the next five to ten years?

I think interoperability’s huge. If you can’t interoperate, it does put hospitals into a position where they’re stuck with a vendor. If that vendor doesn’t get it right, it becomes really hard to whip into place. So proprietary systems that are not open and don’t interoperate with other systems, I think, are a tremendous detriment to the industry itself and so forth.

I think the second thing is we’ve got to make it really easy for people to adopt the technologies at all levels. If we don’t do that, then we’ll have great systems that can talk to each other, but no reason to talk to each other. I think usability has to be addressed. We have to see more innovative user interfaces. We have to have systems that are helping physicians and not just providing data and just kind of being like a ledger.

The third thing is I think we’re not really recognizing the value yet of home health and integrating the patient more directly into the systems and the technologies. I think the third big area that we have to concentrate on is the integration of the patient into the system, and kind of reaching out to the patient. This goes way beyond portals or mobility, I think, which is not really reaching out to our own healthcare opportunities.

Those three things, I think, will probably be the big priorities that I’d love to see. I think it would fundamentally change how healthcare information technology’s done, and thereby, help transform healthcare in the United States.

Amazing that the takeaway is that its easier to buy a gun than to get credentialed as a physician is…