Vince Ciotti retired from a 50-year career in health IT in 2019. He documented the history of the industry’s companies, people, and trends over that time in his HIS-tory series. He can be reached at vciotti@hispros.com.

A reader of your HIS-tory emailed me to ask that I provide more information about you, which is why we are talking today. Describe your background.

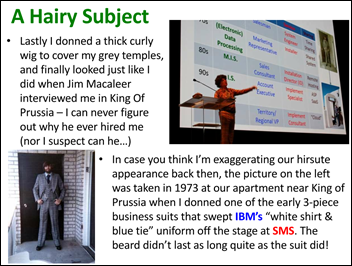

I started in the business 50 years ago, in 1969. I was an English major at Temple University. I couldn’t get a job in any kind of English. There was an ad in the Philadelphia Inquirer for a programmer trainee that said, “see Clyde Hyde.” He was one of the three founders of Shared Medical Systems. The rhyme caught my eye — Clyde Hyde.

I went up for an interview and Jim Macaleer, the president, was dumb enough to hire me. I didn’t know squat about hospitals, computers, or accounting. I learned it pretty quick and had 10 great years at SMS. Then I left them and went to about half a dozen smaller vendors. The first 15 years of my career were with vendors selling to hospitals, the usual job.

Then I got into consulting, first with Sheldon Dorenfest. I met a guy Bob Pagnotta up in New Jersey who’s a real HIS pro, one of the veterans in the industry. We started our own consulting company in 1989, HIS Professionals. It lasted for 30 years, which is probably a world record for consulting firms. Sadly, we just shut it down this year. Now I’m retired.

What will the future hold for health IT consulting firms?

When we started 30 years ago, there were small firms that gave advice to hospitals who were experts in HIT. Sheldon Dorenfest is a classic example. He started many vendors. He started telling hospitals how not to get snookered so bad. Other guys like Ron Johnson, a whole bunch of individual experts, were consultants. Today, I used the word in quotation marks because consulting firms are merely staffing firms. They’re gigantic, billion-dollar corporations that sell you people to do an implementation or to staff. They charge you roughly twice as much as the salary they pay and they make billions.

I’m a little out of touch with this stuff, but the four biggest, I think, are Computer Sciences Corporation, Xerox, Dell — which used to be NTT Data — and Leidos, which got the big Cerner DoD contract. They’re billion-dollar firms that just sell people. Their services are simply to do the implementation of Cerner, like they’re doing for the DoD. Whatever vendor you have, they’ll claim to have somebody that knows it. It’s probably a junior who you’re going to teach to become a more expert person, who they will then charge you more for in the next engagement.

Consulting has gone downhill in my mind. In the early days, it was wonderful. We gave hospitals good advice, saved them a ton negotiating contracts, and felt good at the end of the day to collect our few thousand dollars, not the few million dollars these guys collect today. A different world.

Is it inevitable that a company, regardless of its principles, will eventually get big enough to sell or perhaps to be managed differently?

Two-thirds of hospitals are not-for-profit, one third are for-profit. The non-for-profit ones just don’t know what life is like in a proprietary company. You start a tiny consulting firm, two or three guys, you barely make a few thousand each per month. You struggle to get into six figures. You start hiring a few people, then a few dozen people, you sell more and more, and you grow to hundreds of thousands of revenue, millions of revenue. The next thing is, let’s try to find a sucker to buy us and we’ll get $10 million for our pension fund.

It’s inevitable that a small firm — be it consulting, HIT, or whatever their business happens to be — grows. If they succeed, they’ll look for a buyer, because the original people are now getting kind of old and approaching retirement, like they have a huge stack of funds. So yeah, I’d say it is inevitable. Small consulting firms sadly grow, become giant consulting firms, and look only for the money, not for the good that they could do for their customers.

Your HIS-tory suggests that the same people repeat their success at making fortunes by selling companies that hire them as executives to do just that. What’s it like for the employees who have to just keep rowing down in the galley?

If you could see a bar graph of salaries, it’s mind-blowing. A typical vendor’s C-suite makes tens of millions a year, the managers make high six figures, and what the employees who do the bulk of the work get either in the five figures or just about $100,000. It’s a staggering variance and proportion of income from the C-suite to middle management down to the rank and file.

Where it’s nicest is the tiny startup firms. I was so lucky. SMS was almost a family, just wonderful people. They really gave a damn about their customers. Made sure they delivered the product. The first five to 10 years were just glorious. Then slowly they went public, became a giant, billion-dollar company, and those standards changed. It was purely the money. How can we cut costs and increase income? I bet that’s the truth of almost any company, be it a vendor, consulting firm, or even a for-profit hospital.

How has it changed as hospitals are seeing dollar signs in innovation and startups?

Not much. Every small firm that started way back then had the intention of making money. The successful ones did and got bought up, or bought up others, and eventually sold out themselves for even larger sums. I don’t think that has changed. That’s part of capitalism. I don’t mean to be critical. Believe me, I’m not a communist. I hated communism and Gorbachev is gone. But capitalism has its flaws, too. If making money is the only goal of everybody on earth, it’s a pretty ugly society. It’s the small firms that really care. That family kind of orientation that I really loved. They were the best years, the early years of a small firm.

Last time we talked, I threw out a few company names for you to react to. Let’s start alphabetically with Allscripts.

I get confused. They have bought so much stuff and have so many products. They’re a confusing company. Cerner, Epic, Meditech keep saying just what they are, just what they have. But Allscripts is a little more complicated. I wouldn’t be too optimistic about their long-term future compared to the monsters, Cerner and Epic. But they’re pretty good capitalists and I’m sure they’ll keep making money. I just don’t get too excited about their product line.

Cerner.

They’re the monster. My god, the VA and DoD will keep making billions for them for decades and it’s our tax money. Very sad.

In the original DoD contract, the majority of the money went to Leidos. Of the $8 billion contract, Leidos is going to get something like $7 billion and Cerner only $1 billion for licensee fees. For the VA, wow, the opposite. I think the last note on your site was something like $15 billion is the latest budget estimate for the first part of the VA to go on Cerner. Most of that money is going to go to Kansas City. So I’m very bullish on Cerner from an economic standpoint.

From a product standpoint, they still have a terribly weak revenue cycle. You seem to get a headline every couple of months of a hospital with a catastrophe. Great EMR, solid clinicals, but they still haven’t fixed what used to be called ProFit that’s now called Cerner Revenue Cycle. It still seems to be their weak link.

How will the company’s culture change now that Neal Patterson isn’t involved in running the company his way as the passionate founder?

Brent Shafer was an odd choice. You would think Zane Burke as president would have been the perfect person to be the CEO. He knew Neal real well, knew the culture and all that stuff. Then for some reason they go with this outside search and bring in an outsider. He’s going to be a pure revenue guy who will just want to make money. He doesn’t know much about hospitals or Cerner’s product line. That’s the classic capitalism problem, pure dollars. I don’t think they’ll sell many hospitals, but they’ll make a fortune out of the taxpayers on the DoD and the VA. They’ll stay at the top for a long time.

Epic.

Oh, Judy. Such a miracle. No sales and marketing. She’s so different. It’s just staggering that she’s made such a success and I think it’s going to continue. You know, the large hospital sales are all going to Epic. Many from Cerner, many from Allscripts as the old Siemens customers buy a new system.

Judy has a stunning future. Staggering success. It’s true hospital businesses, not taxpayers and DoD and VA. It’s really hospitals. She refuses to buy another vendor. Has had the same product now for almost 40 years, but the only vendor that has never acquired another vendor. I can think of no other that has been just their own system, period.

They have their weaknesses, too. They’re human. The kids, the young youngsters that they hire that don’t have much experience. The partner consulting firms that rip you off to give a lot of staffing for an Epic conversion. They have no homegrown ERP. Just like Cerner, you have to go buy another ERP and build interfaces. But boy, overall Epic … if I were a large hospital, that’s where I’d go.

Meditech.

Neil Pappalardo gave Judy a lot of advice when she formed Epic. She has followed his rules, which was never acquire anything, just build your own product. In those days, Meditech hired their own people fairly young like Judy did. Built all their own products, no interfaced partners, and they’ve got a complete set of applications.

Meditech probably has the most comprehensive set of apps of any vendor out there. With Expanse, they finally came out with a physician practice system. The last piece they were missing was an integrated doctor piece. So I’m very bullish on Meditech. Their sales were slow for a couple of years. I think for four years in a row, their sales declined, their revenue declined. Last two years, its finally come up. So hats off to Ms. Waters.

I’m fairly bullish on their future. It’s just, darn, there’s not a lot a hospitals that are going to change EMRs. They stick with what they have. They spent so much money on it, they’re reluctant to go to the board and ask for a couple of million dollars for a new system. It’s just hard to get sales.

How much weight do you give technology when you choose your own doctor or hospital?

None. I go for the personality of the doctor. Do you like the guy or the gal? Does she like you? Can you get along with them? Can you smile? Can you talk?

I’ve got a family physician here in Santa Fe who’s so good that I’ll fly here from Florida 2,000 miles just to see him if I’m sick and then fly back. The ones I have in Florida suck. I just can’t stand them. To me, for a doctor, it’s the human side, the personality. Can you talk and you trust them? Do you think they really care about you?

For the hospital side, I had no choice. You may remember that I had a grand mal seizure in January. It’s kind of ironic. After 50 years in hospital computers, I retire and I go to my doctor’s office for a checkup and I have a seizure and they put me in a hospital and stick a computer in me. I got a pacemaker inserted in me and it saved my life. I’d have probably died. Still don’t know the cause, some kind of micro-stroke, but the pacemaker has been a damn miracle. Doctor’s say the battery’s good for 14 years. I told him I may not be good for 14 years. I’m thrilled to have it and it’s working like a charm.

The technology for the patient, when it’s interfacing with you personally, is priceless. Boy, the advances are glorious. You know, my father or grandfather would have dead with this seizure, and I’ll probably get 10, maybe 15 more years. So I love technology on a personal standpoint. But as far as the hospital’s computer system, I couldn’t care less.

I went to UCLA Medical Center and they have Epic. It was phenomenal to be able to see my whole chart on the screen with the security code and all that stuff. That was nice. And if I go to other Epic hospitals, they’ll know all about me. But a fourth of hospitals are are Epic, a fourth are Cerner, a fourth are Meditech, and a fourth are CPSI. If you’re admitted because of an emergency, you have no choice. If I had the choice, I would probably go with Epic now that I’m on that with my UCLA record, but again, when there’s an emergency, you have no choice. You go where ambulance takes you.

How do you see the dynamic among health IT vendors, salespeople, and health system executives?

In the early days at SMS, I was an early education manager. I had to train the new installers, as we called them then. Today they’re consultants, I guess, but then they were IDs, installation directors. I had a two- or three-week class to go through every single report, every single profile option, every master file, every transaction, whew. Took two to three weeks to train them and then they could still go out and botch up their first install. Took a couple of installs before they knew what the heck they were doing.

We hired salesman at SMS and they spent one day walking around all the offices, saying hello, shaking hands. Who are you? What do you do? Oh, OK. Then boom, after one day, they were out there selling. They had no idea what they were selling. It doesn’t matter. Sales is commissions. If you sell a lot of systems, you make a lot of money and you get promoted and you become a big cheese. If you don’t sell any systems, you get fired. You’re going to go to another company and try again.

You don’t learn the product. You haven’t been an installer or a customer service rep. You haven’t worked with the system. You have no idea how the system works. What you know how to do is smile, be pleasant, buy lunch, buy dinner, shake hands, be charming, have people trust you, get them to sign the contract, and then run like hell because you’ve got to make some more sales.

That hasn’t changed to this day and never will. It’s capitalism. There’s nothing wrong with it. It’s just what life is like. Think of a used car salesman. What does he or she know about the engine, the transmission, or the differential of a car you’re buying? They know that they want you to sign quick before the end of the day. It’s not immoral. It’s not nasty. It’s just the truth.

Hospital, it’s so sad, they just spend time talking to salesmen. Hospitals should ask to talk to their installer. Who’s going to put the system in? I want to see him or her, have them walk around my hospital and tell me what good or bad things are going to happen. No hospitals do that, but that would be the dream, to see your installers before you sign that contract. Salesmen again are not immoral. They’re not liars or nasty people. It’s just their job. The job of used car salesman is to get you to sign that contract and HIT is not much different.

What do you think about the recent health IT IPOs?

It’s part of capitalism. Initial public offering is inevitable. The reason you form a firm is to get that stock on the market. Get double, triple, quadruple and away you go.

I joined in SMS in 1969. I got the 200 shares that Jim Macaleer gave to every new employee. I went to my boss and said, what’s a share? He explained it to me, and I said, what’s it worth? He showed me that it said 1 cent per share, so my 200 shares were $2. I was going rip it up, but he said wait five years, you’ll be very glad. Sure enough, we went public around 1975. I think it was $14 a share. The stock had split several times before then, so my 200 shares were now like 800 or 1,600 shares. I was suddenly a very rich man. That’s the goal of capitalism, money, and it’s going to be the future as well as the past. That’s the American way. Nothing wrong with it, nothing immoral, it’s just the truth, it’s what our economy does. Nothing but money.

The only time I’ve sensed that you were star-struck was when you visited Judy Faulkner at Epic’s campus as you described in your HIS-tory. What surprised you about that visit?

She’s a very humble person. I walked into the lobby. There’s nothing massive, it’s just a lobby. Usually what you get is that the executive secretary comes over, asks if you want coffee, takes you into some big, glamorous conference room, and then after five minutes — there’s always a delay — in comes the executive. Shakes your hand, has two or three assistants on either side of them because they don’t know all the answers to your questions you’re going to ask.

I walked into Epic. I’m sitting in the lobby, you know, handsome couch. I look in the bathroom over there. There’s only a toilet, there’s no urinal. It’s a very female-oriented company. It’s kind of cute. All of a sudden, across the lobby, here comes this lady walking towards me. I suddenly recognize that it’s Judy Faulkner. No executive secretary, no setting me up in a big conference room.

She walks over, shakes my hand, takes me into her fairly small office, sits down, and says, “What are you here for? What do you want to do?” She’s such an open, humble, honest person. If you went to visit Brent Shafer at Cerner, you would probably get 45 minutes of introductory talk from other people before he finally came in the room, with seven assistants to answer all your questions. Boy, she just sat down and talked and said such honest comments. It was amazing. So yeah, she’s unique in our industry. Very a wonderful lady.

The one sad thing about her and Epic is that she is the company. I think she’s as old as me, 74, 75, something like that. At some point… she won’t retire. She’s not that kind of person. Epic has been her life and she’s very proud of it. I don’t blame her. But at some point, she’s human. She’s going to die, she’s going to retire, she’s going to have a heart attack. Who knows? Her successor can be nothing as good as she is. The company cannot have as bright a future once Judy is gone. She is the company. The company is her.

Sort of like Cerner and Neal Patterson, maybe Meditech and Neil Pappalardo. Neal and Neil slowly started to give the power of the company to their subordinates. I think Judy still runs Epic completely. I just can’t see a replacement for her. She is the company, personally.

Who are your heroes of our industry?

The folks at SMS, just because it’s the company I knew. Jim Macaleer and Harvey Wilson were the two bosses. Jim was just an incredible guy. He could be a mean son of a gun at times. A real Theory X manager. He was tough, but then the other half of the time he was funny, he was charming, he was pleasant. He just died, I think it was last year, 18 months ago. I’m really sad that we had to lose him. Harvey’s still around and doing wonderfully well. He not only helped form SMS, he was the number two at SMS, but then he formed Eclipsys and sold out to Allscripts.

We’re having our SMS reunion in a few days, the 50th reunion of SMS. One hundred and fifty people are showing up in King of Prussia and Harvey’s giving an introductory speech. To me, that’s a wonderful life, to have such a success and so many people coming to see you again and such a family feeling.

I can’t think of too many others that I really respect, that is until you get to the current vendors, and Judy would be at the top of that one.

How has retirement been versus what you thought it would be like?

Well, that’s an interesting point, because frankly I’m bored to tears. I’ve always been into motorcycles, Honda motorcycles. I started as a kid and that’s become my full-time occupation. I have six of them. I just sold one. I used to have seven, one to ride every day.

I literally do ride a motorcycle every day. I get home about 1:00 or 2:00 from lunch and then wonder, what the heck am I going to do? I usually take a nap on the couch and I’m bored to tears. So I’m looking into some hobbies, other hobbies, maybe learn the piano, some other stuff. I love to look your site every morning, five minutes to get an update on what’s going on. Still keep up with a lot of good old CIO friends and consulting friends and even some people from vendors and we get together often.

Retirement is a bit of a shock. I had no idea what I was going to do and I still don’t. I work one day a year. I teach a class at Brown University, in their MHA program. I’m going out there two weeks and I probably spend about a week updating my vendor review and present it to the students. I should say “students” in quotes because they are CFOs, CMOs, CNOs, very sharp people. I probably learn as much from them as I teach them. But that two-hour class is the only thing I do all year.

When you meet someone and they ask what you do, they expect you to describe your job as your primary identity. How do you introduce yourself now?

I’m usually on a motorcycle when I meet somebody. We start talking about Hondas. I don’t meet professional business people any more, but if I sit next to someone on an airplane who wants to know what I’ve done, I tell them that for 30 years, I was a hospital computer consultant, and then for 20 years, I used to work for vendors in hospital computers, and now I ride motorcycles. That kind of sums it up.

You’ve got to think ahead of retirement. I didn’t and I’m sorry for it. I didn’t have any plans at all and I’m struggling with it now. If I didn’t have the Hondas, I’d go crazy.

Do you feel any springtime pull toward the HIMSS conference?

I live down in Orlando right next to HIMSS. I used to go every year, and the thing got so big. I started to get totally bored to tears with 40,000 people in one hall and hundreds of vendor booths. At the booths, the few old guys or ladies I knew were just not there any more. Dozens of young sales reps. So no, I have lost my affection for HIMSS. When it was small and you knew everybody, it was wonderful. It was glorious. It was a family kind of thing. As it has grown to the gigantic size of today, I haven’t gone for the past two or three years.

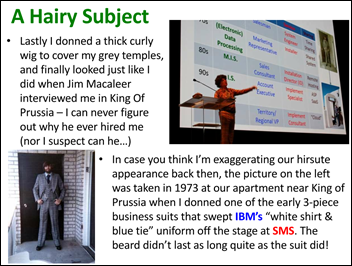

When I presented there, that was a lot of fun. Thank you for having me to do that HIS-tory presentation there and dress in the wacko hippie suit. Got me into the whole HIS-tory file, those 120 episodes you ran on your website, but I had never presented at HIMSS. If they wanted me to present the HIS-tory thing again, I would do it. That I love. But to just walk around the halls and meet all those green salesmen who I never knew and they never knew me bores me to tears. I can’t stand it.

Not many people seem to be interested in health IT’s past. How would you convince someone to read your HIS-tory, either now or 25 years from now?

It’s the same as reading the history of the human race, history of America, history of Europe, history of homo sapiens. You can only learn from the past. You can’t learn from the future. It’s not here yet. The mistakes made in the past will be made in the future unless you learn from them and change them. It’s such a priceless thing.

I just bought a book on the history of warfare. I’m a reader, I own thousands of books. And the first page has an incredible statistic. Of the past 5,000 years of human history, roughly back to 3000 BC, only in about 300 years have we not had a war. If you haven’t read history and learned that, you’re not going to appreciate the risk that we’re going into World War III with nuclear weapons and all this horrible strife between small countries around the world. You have to learn from the past to be able to avoid those mistakes in the future.

In HIT, what vendors did back in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, they’re doing today in the 2010s into the 2020s. Only when you read it and learn what they’ve done will you know what they’re going to do in the future and how you can avoid it. You avoid being a victim and help your hospital get a little bit of its money’s worth. I think it’s priceless in any industry — automobiles, transportation, education, automation, you name it. You learn from the past to do better in the future. If you just go into the future blind, you’re going to make the same mistakes.

What will your epitaph say?

If I could be remembered for anything, it would probably be my HIS-tory files, which I thank you for posting over such a long time, two and a half years. I hope some of the future CIOs read them and learn from them. I hope that’s what they remember me by, the guy that warned them about not repeating these mistakes of the past.

Couldnt help thinking of this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QBV7HRGM7ns&t=174s