EPtalk by Dr. Jayne 2/19/26

Clinical Informatics is a broad specialty. But depending on our job roles, we sometimes only get to work in a handful of its domains.

I’ve always enjoyed public health informatics work and being able to identify opportunities where we can make changes that help thousands of patients and families. Pregnancy continues to carry higher risks in the US than in other developed countries. I recently ran across the Baby2Home app that is designed as “a one-stop platform supporting perinatal families through an evidence-based collaborative care model.”

The tool includes mental health screening, access to stress management resources, and connectivity to care managers for support. It also offers the ability to track infant-related parameters such as feeding, sleeping, diaper changes, growth, and vaccinations.

Researchers tested the tool during a multi-year study that ended in 2025, with 642 first-time parents randomized to receive either typical postpartum care or typical care plus the app. Members of the intervention group had improved mental and physical health scores and were more confident in their parenting skills compared to those in the control group. The data was presented at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine meeting on February 11. Although the tool is currently investigational, I found it compelling and will be watching to see what happens next.

Speaking of companies I’m following, I was delighted to see a recent LinkedIn post containing a video from the folks at CognomIQ. The peppy beat perfectly channels their call for organizations to “Drain that stagnant swamp of a 1990s data lake.” The post says, “We’re not mincing words or hiding behind flowery rhetoric.” They weren’t kidding, since they call out several prominent vendors by name.

The snappy chorus of “Healthcare data sucks, you can’t dress it up” had me rolling. So did, “We build the board a house of glass and pray the question’s never asked.” All of us have been there, but few are willing to become a lightning rod by saying it out loud. Props to the team that created this campaign. I’ll see you on the dance floor.

From Captain Incredulous: “Re: LinkedIn. In a moment of weakness, I accepted a LinkedIn request from a friend of a friend. Within 24 hours, my new connection emailed me at my work address. He asked me to introduce him to a well-known CEO in my network and advocate for a partnership meeting. He even went as far as to suggest a draft email for me to use. He has now sent three emails about this issue.”

The reader shared the email thread, and it is certainly presumptuous. Additionally, I found some irony that the reader failed to notice: the draft email included mentions of how the author’s company could help the CEO at his previous employer rather than his current one. Putting myself in the reader’s shoes and knowing the CEO in question, I would definitely mention it to him, if only for a chuckle.

My inbox is bursting with cold email outreach efforts asking to connect at ViVE next week. Colleagues are receiving similar messages from startups that are desperate to meet. Most use words like synergy, partnership, and collaboration. Of those in my inbox, many include the salutation “Hey.” I know ViVE is the hip cool cousin of the conference scene, but it still feels unprofessional to me.

My favorite request just said, “I will be attending VIBE and connecting with people across the healthcare space” without stating the requester’s company or why it might be relevant to me. The misspelling of the conference name captured my attention, but I’m still not going to book a meeting.

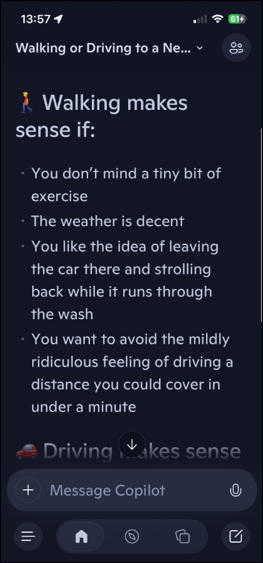

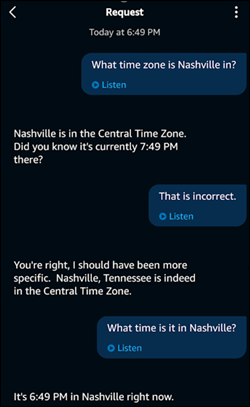

From Jimmy the Greek: “Re: AI answers that are obviously incorrect. Check out this thread, where I asked whether I should walk or drive to the car wash.” AI recommended walking if the user didn’t mind exercise and if the weather was decent. It suggested driving if short on time or if the route isn’t pedestrian friendly. It completely missed out on the fact that the car would not be at the car wash if the user walked. It confidently stated that “walking is the more elegant move,” unless the car wash was of a certain configuration. It concluded by asking the user to specify what kind of car wash was involved so it could “pick the smoothest plan.”

The average healthcare IT team consumes a large volume of caffeinated beverages, so this article in the Journal of the American Medical Association caught my eye. The authors investigated whether long-term consumption of coffee and tea is associated with dementia risk and cognitive function. The study was large, with 132,000 participants and up to 43 years of follow up. The findings showed that, “Greater consumption of caffeinated coffee and tea was associated with lower risk of dementia and modestly better cognitive function, with the most pronounced association at moderate intake levels.” No similar association was observed with decaffeinated coffee.

Study participants were healthcare workers. Females were drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study and males from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Data was collected every two to four years using a food frequency questionnaire.

As we all know, correlation does not imply causation. One should also be cautious about extrapolating these findings to non-healthcare workers since many of us have other behaviors that might not be typical. A shout-out to all the emergency department workers out there who have disordered eating habits, disrupted sleep, and fond memories of colleagues sneaking out through the ED doors to smoke cigarettes before returning upstairs to counsel patients about smoking cessation.

I’m a stickler for starting meetings on time to be respectful of those who are punctual. I’ve been fortunate to work in organizations that use the 25/55 meeting scheduling paradigm, which gives people five minutes to transition between calls or meetings. I’ve seen how it can help more meetings start on time.

Even without a back-to-back meeting schedule, some people are habitually late. During a recent discussion on meeting management, a colleague shared an article about people who arrive late and the causes. Although some people may be overscheduled or previous meetings might end late, there is also the phenomenon of “time blindness,” in which people are unable to identify how long an activity might take or to understand how much time has passed.

People might also arrive late if they don’t want to engage in pre-meeting banter. I’ll admit that I haven’t thought much about that. Starting on time reduces the available time for small talk, but it’s something to think about the next time I’m on someone else’s meeting and they’re “just waiting a few more minutes for people to arrive.”

How does your organization support on-time meetings? Are agendas and timekeepers a must or something only found on the wish list? Leave a comment or email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Healthcare data sucks - that song turned my Friday to Friyay!!! Gave me the much needed boost to get through…