The story from Jimmy reminds me of this tweet: https://x.com/ChrisJBakke/status/1935687863980716338?lang=en

Curbside Consult with Dr. Jayne 12/24/13

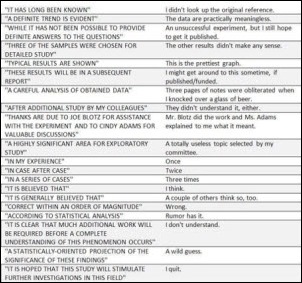

I’ve seen this graphic about the interpretation of scientific jargon multiple times. It seems to turn up on Facebook or in an email every now and then. I read a fair amount of scientific literature and thinking of the alternate meanings always makes me smile. You could use it to play a kind of Mad Libs substitution game to liven up whatever article you’re reading.

As a medical informaticist (Now improved! With Board Certification!) I read the literature with a pretty critical eye. That probably goes back to my medical school training when I learned the importance of understanding whether the patient population in a clinical study was similar to the patient in front of me before deciding whether to use its data to alter my treatment plan. I’ve also read far too many studies that lack statistical validity or pursue therapies that although clearly proven are just irrelevant in real-world medicine. I’ve spent most of my medical career in the community rather than in the academic space and know that they can be vastly different environments.

As part of my preparation for taking the American Board of Preventive Medicine Clinical Informatics certification exam, I attended the AMIA Clinical Informatics Board Review Course. Although it was great to actually sit down and discuss informatics with others in the field, it was a little surreal at times. I’m used to working in a bit of a vacuum – most of the time I’m the only clinical informatics professional in any given meeting – so being surrounded by scores of my peers was a bit overwhelming. The fact that several people in the room were the authors of the texts I had been reading to prepare added to the intellectual climate.

By listening to some of the questions asked during the class, one could tell that some of the attendees were significantly more academic than others. I ended up spending most of the breaks off to the side with several attendees who were more community/clinical-based like I am. After the course, AMIA launched a listserv for attendees and being a silent participant has been entertaining. Watching highly-intelligent physicians interact over minute details of one thing or another can either be educational or mind-numbing depending on the topic and the people involved. Since we’re in a fairly new field, the group is very good about bouncing ideas off one another and one recent series of posts revolved around the idea of the environmental scan.

In a nutshell, an environmental scan is a review of the political, environmental, social/cultural, and technical factors around a business, industry, or market. Organizations benefit from doing an environmental scan periodically to understand the factors influencing their business and the challenges they may face now and in the future. One member was looking for evidence demonstrating a clear return on the efforts of doing such a systematic review. Her employer wanted it proven before they agreed to conduct one. Respondents quickly piped up with examples of business practices that may not be evidence-based but are good ideas, such as paying bills on time (which is pretty funny in and of itself) but one response had me laughing so hard I had to physically get up and walk around after reading it.

This particular scholarly work was published in the British Medical Journal and is titled “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomized controlled trials.” Although it’s subscription-only, the abstract is available. The authors set out on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials “to determine whether parachutes are effective in preventing major trauma related to gravitational challenge.” Essentially they did searches of Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and other sources to try to find literature proving parachute use is a good idea. Not surprisingly, they could not find any randomized controlled trials of “parachute intervention.” The conclusions are what pushed me over the edge (somehow the more formal-appearing British spellings make it even more humorous):

As with many interventions intended to prevent ill health, the effectiveness of parachutes has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation by using randomised controlled trials. Advocates of evidence based medicine have criticised the adoption of interventions evaluated by using only observational data. We think that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence based medicine organised and participated in a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.

It just goes to show that even those among us who are most academic can still have a sense of humor. It also reminds me (along with the original “show me the money” question about the environmental scan) that there are a lot of administrators and other people out there who still don’t understand what we do or what we can bring to the table as part of this new discipline. I’ve got a couple of people in mind that I’d like to enroll for that parachute trial. Perhaps you know a few candidates? Email me.

Email Dr. Jayne.

Liked your post but parachute metaphor is incomplete. What us rational evidence based folks would say is not that we want proof that parachutes save lives. We want a conversation where we say are parachutes a low cost or a high cost way to save lives? Is it a reliable way of saving lives? Is there a better way to do it? why does the data show we use the parachute hundreds of different ways? Are they all just as good? The intersection of hitech, evidence base, and payment reform is here…somewhere.