"A simple search on the named authors (when presented) reveals another carefully concealed attempt at Epic influence..." The site is…

Monday Morning Update 11/1/10

From California Dreaming: “Re: privacy statement on Amazing Charts Web site. Funny stuff!” It is funny. “ … USE COMMON SENSE WHEN USING THIS SITE AND THE AMAZING CHARTS SOFTWARE, AS WE ARE NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR YOUR LIFE AND DECISIONS … USE COMMON SENSE WHEN GETTING INFORMATION FROM THE INTERNET, SOFTWARE, LIBRARY, ENCYCLOPEDIA, DOCTORS, OR ANYBODY ELSE. WEAR SUNSCREEN, USE SEATBELTS & CONDOMS WHEN APPROPRIATE, AND PROTECT YOUR EYES WHEN USING POWER TOOLS.”

From Ex-Concerro!: “Re: layoffs. Concerro laid off all but one of its QA department and demoted the VP of engineering. They have been unable to stabilize the product since 5.0, which was an attempt to turn a shift-bidding product into a scheduling product.” Unverified.

From Personal Problem: “Re: palm biometrics for patient ID. I would refuse to use it since those can be intercepted or hacked. Then what — get a new palm?”

From Nancydoll: “Re: GE Healthcare IT Enterprise Solutions. Laurent Rotival ousted – there on Monday, gone on Tuesday.” Unverified. GE doesn’t comment on personnel issues. His LinkedIn profile is unchanged.

From Aldonza: “Re: PKI security. Have solo practitioners or small groups tried it? Some technologists say its simple to implement, others are skeptical.” Your comments are welcome.

The Dubai government talks up HIMSS Middle East 2010, expecting 300 people at the November 8-10 conference.

A new report by HIT research and advisory firm CapSite covers the HIM market: vendor penetration, mind share, buying plans, etc. based on information gleaned from 500 hospitals. They sent over the full report for me to check out and it was interesting – hospitals are considering lots of new HIM vendors for buying opportunities of an extremely short time frame (less than a year). The table of contents is here (warning: PDF).

The eClinicalWorks user conference started Sunday in Orlando, with over 2,500 attendees.

Weird News Andy rises to the “beer bottle in the colon” challenge, saying, “I raise you some precious gems. I suppose this guy wanted to be the King of Diamonds. what a card!” Police in India arrest an airline passenger on the rumor that he is carrying diamonds. His bags were found to be empty, but he fidgeted suspiciously during questioning, claiming his hemorrhoids were acting up. The hospital X-rayed him and found 42 condoms’ worth of precious stones that he had swallowed. The diamonds were re-mined with the help of laxatives and bananas.

From the last poll, it’s an even split whether “best places to work” companies are really all that great to work for. New poll to your right: will you be participating in the upcoming HIMSS Virtual Conference?

Epic put up a fun Halloween-inspired home page for the weekend, including some bats randomly flying around (since they’re in the Midwest, that made me think of John Candy and Dan Aykroyd in The Great Outdoors, if you’ve seen that scene).

Quality Systems (NextGen) reports Q2 numbers: revenue up 14% to $81.5 million, EPS $0.46 vs. $0.41, with both revenue and earnings falling short of expectations. The Street was looking for $85.7 million and $0.49.

Meditech’s quarterly numbers: revenue up 23%, EPS $0.89 vs. $0.57.

CPSI’s Q3 numbers: revenue up 24%, EPS $0.45 vs. $0.37.

Memorial Healthcare System (FL) signs up for ExactCost’s Cardiovascular Service Line software, allowing it to support activity-based costing.

Chubb Group adds an insurance program for the healthcare IT industry, covering defective software that causes patient harm, liability for data breaches, and the cost of notifying consumers of a data breach.

States don’t have the expertise or money to develop the Health Insurance Exchanges, consumer insurance marketplaces that are mandatory by 2014. HHS announces Early Innovator grants that will be available to up to five states who develop systems that other states can use. HHS announces said that it will announce financial help for all states in February.

A Massachusetts court gives the OK for a private equity firm to take over Caritas Christi, Boston’s Catholic hospital system, for $895 million. Cerberus Capital Management will turn it into a for-profit entity. Closing is expected within a month. The company can cleave ties with the Catholic Church for a $25 million payment.

Microsoft’s HealthVault personal health platform will enter the Chinese market as the company signs an agreement with iSoftStone Information Technology. The announcement says that a total of 150 hospitals are connected to its platform worldwide, which seems pretty skimpy.

St. Joseph’s Hospital (CA) devotes its annual gala to raising money for its EHR, raising $160K from 600 guests who got to play around with iPads and the Microsoft Surface coffee table thingy.

West Penn Allegheny Health System (PA) will lay off 400 employees, most of them from West Penn Hospital, in a restructuring plan.

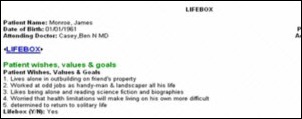

I really like this idea: a team from Norwood Hospital (MA) and its community health partners use a $200,000 grant to create a LifeBox within their EMR. Hospitalists interview patients about their backgrounds and record the wishes, values, and goals of those patients in their LifeBox so that other caregivers can understand what’s important to them. I think Norwood is one of the Caritas Christi hospitals that will soon be going for-profit.

Sponsor Updates

- Three hospitals in Sweden will implement iMDsoft’s MetaVision for their ICUs, ORs, and PACUs.

- eClinicalWorks announces its Version 9.0 and a new site, 100millionpatients.com, as a patient portal with PHR access.

- RelayHealth’s RelayClinical EHR receives ONC-ATCB certification from Drummond Group.

- Allscripts was a joint presenting sponsor of the Walk to Cure Diabetes held October 30 in Raleigh, NC.

Article Review

Health information technology: fallacies and sober realities

A reader asked me to review this paper, which just appeared in the October issue of JAMIA.

The first thing I noticed is that it was published as a “viewpoint paper.” Rightly so: it’s a lot of footnoted opinion. The problem with opinion papers is that those who agree with their conclusions laud the work as pivotal, long-overdue, and seminal. Those with different points of view say that fancying up personal opinions in a published article, by grant-funded academics, is no more credible than watercooler chatter.

It’s a mildly interesting piece, but the only folks likely to proclaim it as a work of great insight are those who have already convinced themselves that electronic health records, the companies that sell them, and the providers use them successfully are clueless and/or evil (I should mention that the authors use the broad term health information technology, but are writing specifically about clinical information systems from what I can tell).

My red flag went up immediately with this sentence in the abstract: The twin issues of the failure of HIT adoption and of HIT efficacy stem primarily from a series of fallacies about HIT. An article that can definitively state the reason that providers don’t use EMRs or that they underperform would indeed be useful, right? Only if the statement is backed by proof, which I don’t see here.

The authors come up with a Letterman-like list of 12 "misguided beliefs about HIT.” Who holds these beliefs is not documented, but the implication is that the authors observed them in some capacity. Maybe they are right and these exact 12 misguided beliefs mean that HIT is in need of a reboot. Or, maybe they worked back from the conclusion that HIT needs a shake-up and selectively chose the ones that made their case.

Here are the 12, reworded to make the opinions of the authors clear:

IT risks are not as minor or easily manageable as IT people think.

The article says that “many designers and policymakers believe that the risks of HIT are minor and easily manageable” (without referencing how they know that). They correctly observe that it’s hard to develop and implement systems as planned, that humans are fallible, and that software problems are hard to prevent and can have widespread impact. Everybody reading that paper or this post probably already knows that.

Being an opinion piece, the authors recommend as a solution: regulation and/or independent, external validation. I agree that some degree of oversight is needed for specific types of HIT. That’s still just an opinion (that of the authors and me). I’d like to have seen citations of articles researching the outcomes of getting the government involved in product regulation.

HIT is a medical device.

This is stated as a fallacy: “the belief that HIT can be created and deployed without the same level of oversight as medical devices.” That’s not really a fallacy since that’s the current state. It’s just another way for the authors to opine that the government should start regulating clinical software.

The article makes a good (but obvious) point: humans can’t be relied on to catch computer mistakes. It doesn’t make another equally good and obvious point: computers catch a lot of human mistakes. Based on the conclusion that HIT can’t be trusted unless it’s regulated, hospitals should immediately stop using bar code scanning, CPOE, clinical decision support, etc. because they might mislead gullible but otherwise error-free clinicians.

The following unreferenced conclusion about lack of FDA oversight would have been struck out of any article not labeled as an opinion piece: “The current approach can no longer be justified.” Says who?

Humans are not the problem when software fails to improve outcomes or efficiency.

This is another obvious point. Outcomes are system-related (people, processes, oversight, etc.) Bad users acting individually aren’t usually the problem. I also don’t know anyone who would say that — is this really a common fallacy that required debunking?

Just because clinicians use a system doesn’t mean it works.

The conclusion seems to be that “meaningful use” is situational, which is absolutely true. Sometimes users don’t get a choice in the decision to use or not use a system. Still, we’re talking about highly educated and licensed professionals who still bear the responsibility to speak up if a system is unsafe.

It’s also true that the same problem happens with paper. Individual providers don’t necessarily get to decide for themselves whether to complete certain kinds of paper documentation, regardless of whether they see value in that activity.

Clinical work is messy and can’t be rationalized into something linear.

It is true that programmers think linearly and logically, so IT systems are designed that way. But it’s also true that software often organizes and standardizes, which is the only hope to improve medical care beyond individual decision-making with whatever information is at hand.

This is the “medicine is an art” argument, which has some merit. But the argument that primitive clinical decision support systems interrupt clinician workflow (true) means we need “new paradigms for effective HIT design” is a leap. I don’t really know what they mean by that. I suspect the authors don’t, either – it’s easy to say that today’s systems don’t always perfectly match the work clinicians do, but hard to say exactly what they should be doing differently. Today’s systems continue to evolve, albeit a lot more slowly than I’d like.

Rightly or wrongly, clinical practice — within the same organization, on the same medical service, and by individual practitioners — is inconsistent, situational, and often illogical. Paper couldn’t fix that problem and neither can technology. I’m all for taking shots at the HIT industry where it’s warranted. However, if the argument is being made that clinical work is admirably illogical, then turning programmers loose to somehow pave that particular cow path doesn’t seem like a great idea.

Front-line users are stuck with poorly designed and inefficient IT systems because people above them incorrectly think they will solve problems.

I’ll buy that. End users often get a few productivity aids, but are stuck with awful features otherwise. Hospital executives make decisions for employees whose work they can’t begin to understand.

I found this statement a bit of a lark even though I agree with it in a pie-in-the-sky kind of way: “Healthcare does not exist to create documentation or generate revenue, it exists to promote good health, prevent illness, and help the sick and injured.” If the authors have figured out a way to improve healthcare by eliminating documentation or working for free, then I’d like to hear it. If not, then they should not blame software for reflecting reality.

Providers drive the design and adoption of HIT by voting with their dollars. If products aren’t meeting their specifications, they presumably wouldn’t be buying them. Software reflects the way things are, not the way we wish they could be. Vendors would go broke fast trying to sell systems that don’t reflect reality.

Software designers assume that their software is perfect and any problems must be due to bad users. Computer consistency is not the same as intelligence.

I’ve worked in the industry for a long time and I’ve never heard this belief expressed. Software designers (among which are often the users themselves) know the limits of what they can envision and deliver. They expect bugs, reworking unforeseen design flaws, and improvement by iteration.

Software is designed to do things that humans are not good at: keeping lists, calculating, and reminding. There’s no doubt that sometimes user interfaces (like the Three Mile Island example cited) are misleading or allow important information to be missed.

The conclusion is that “HIT must support and extend the work of users,” which sounds nice but is hard to define. It also seems to presume that none of today’s HIT systems do that, which I would say is just plain wrong.

HIT systems are designed for a single user working on a single patient doing individual discrete tasks.

That’s often true. Systems don’t always optimally facilitate collaboration, but that doesn’t mean they are worthless. It’s early in the HIT adoption game, so today’s systems are actually yesterday’s systems, designed in the 1980s and 1990s with simple functionality: record, calculate, display. Customers are buying those systems, though, and deriving benefit. You don’t see many hospitals going back to paper.

I agree with this argument. We need better systems that go beyond today’s 1980s paradigms of simply automating repetitive tasks. However, as long as customers keep buying available systems instead of working to demand and design these new ones, this kind of innovation probably won’t happen.

Computerizing paper processes doesn’t help much. Paper will persist.

The article says that paper forms are more than data repositories – they are artifacts that support situational awareness and coordination. Suggesting that “HIT designers and administrators” are unaware of that fact is insulting.

Hospital executives and HIT vendors may toss around the “paperless” buzzword, but nobody’s paperless and that’s not necessarily bad. I don’t see either providers or vendors who are so enamored with the “paperless” concept that they fully believe that paper is bad and computers are good.

Frankly, I don’t get why this is a “fallacy” and a bad one at that. It seems too obvious to be a fallacy.

Putting clinicians together with programmers won’t necessary create usable systems.

That is undeniably true. Asking users what they want and then turning programmers loose to deliver it is not exactly IT leadership. Users are way too limited in their perceptions and preferences. Their world view is often limited to a single facility, profession, and specialty. That makes it hard to design a one-size-fits-all application that vendors can sell to hospitals of all sizes (which should have been on the fallacy list – that no product meets the needs of all sizes and types of hospitals, no matter who else has implemented it).

The article suggests involving a lot of people who aren’t working in the industry (like the authors). That sounds great on paper, but software designed by committee is usually terrible, a Frankenstein of pet ideas that make the cut only because the most aggressive and outspoken committee members convinced the silent majority to agree.

Conclusions

The authors of this paper are academics. I like their objectivity, but I’m left with the feeling that they are disillusioned about this fact that is distasteful to them: both healthcare and healthcare IT are businesses that, rightly or wrongly, make decisions based on their own self-preservation, not high-minded academic ideals.

If HIT is as bad as the authors say, why are customers buying it? Nobody’s putting a gun to their heads (although HITECH is a step in that direction).

The authors conclude that the right HIT metric should be not be adoption or usage, but population health. They are correct. I’ve been saying that for years. We’re still in the primitive stage of HIT, automating simple care delivery tasks that may or may not have profound health impact. People are paying millions of dollars for systems that sometimes behave like 1980s database programs: they accept data entry, store it, and regurgitate it in ways that are useful, but hardly revolutionary. I agree that in many cases, providers should be spending the money elsewhere. But it’s their money.

It’s easy to criticize any industry for doing the wrong things or not doing the right things. It’s also mostly irrelevant. MBA 101 tells you that business aren’t good or bad, they simply meet the needs of their customers. Otherwise, they would cease to exist. If you don’t like vendor products, blame the customers who are buying them (and who in many cases, directly influenced their design). As an analogy, it’s too easy to blame the fast food industry for obesity than to fault their customers for creating the demand in the first place.

The track record of vendors who rewrote systems from scratch certainly doesn’t encourage more of the same. The development of Millennium nearly took Cerner down. Soarian turned Siemens into a punch line. A vendor thinking about rewriting a major clinical suite will need to be willing to live without 5-7 years of sales (since prospects don’t want to buy an orphan product) and had better not have impatient shareholders or investors. Not many vendors are strong enough to sit on the sidelines for that time, much less to amass the resources and expertise needed to undertake such a project.

I have less confidence than the authors that adding government oversight and a bunch of non-industry academics to the mix will make things better. That’s how the government does things, and government systems reflect all the bad characteristics the authors decry: they are user-unfriendly, task-oriented, outdated, and massively expensive.

I agree with two major themes from this article: (a) independent oversight of clinical information systems would be a good thing, and (b) the state of healthcare software is as disappointing as the state of healthcare itself. I didn’t need this article to tell me that, though.

RE: JAMIA

Hmmm…didn’t read the full article (though I’m not sure I’d want to bother) because I’m too cheap to buy a membership, but it sounds like these folks need a reality check. Frankly it sounds like a job for No Duh Man.

No company is ever going to deliver what they seem to want – a software system that can treat a human being without another human being’s judgement being called in. HIT is a tool. Period. You can use the tool the way it is meant to be used (i.e. use a hammer to pound in a nail) or you can use it poorly (i.e. use a hammer to perform surgery on a NICU patient).

Use the tools for what you can but don’t expect them to do the job for you. HIT can help automate health alerts, trend your pediatric patients’ growth and maybe even help you tap into some of those MU dollars so you can keep your doors open and treat more patients more effectively.

Happy Halloween…here’s to more ‘treats’ than ‘tricks’.

More than 500 words! “No company is ever going to deliver what they seem to want – a software system that can treat a human being without another human being’s judgement being called in.”

The only medical device makers who do not seem able to accomplish getting it right (even on the 10th try) are those who make the devices that are the subject of your essay. Might it be, might it just be, that other medical device producers have better quality control and can get it right the first time because they have to abide by the FDA’s quality processes?

Great essay and rebuttal anyway. I like the way you write.

“RE: PKI security. Have solo practitioners or small groups tried it? Some technologists say its simple to implement, others are skeptical.”

The HIE-Bridge Health Information Exchange (HIE) in Northern Minnesota has been using Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) since it was built by MEDNET in 2009. PKI allows for the protection of the over 3 million records in the HIE-Bridge system by providing a two-factor authentication system. After each healthcare professional goes through a simple process of in-person identity verification, the user is added to the HIE-Bridge system via the release of a digital credential. Then, a user may access the HIE-Bridge system by visiting the web portal and entering their PIN number. Users must access the web portal on a computer with their digital credential, but have no other limitations or impediments.

The process of creating, distributing and utilizing each digital credential is made easy by MEDNET’s Privacy & Security software module. Thus, each user must verify their identity only once, receive a digital credential, and then use the HIE-Bridge system with the same ease as accessing an online banking site. In this scenario, PKI has been implemented as an easy-to-use solution for secure authentication. Similarly, PKI is leveraged in the HIE-Bridge network to provide data integrity (“the transferred message has not been compromised in any way from the original message”), data confidentiality (“only the intended recipient can read the message”) and data non-repudiation (“the transferred message has been sent and received by the parties claiming to have sent and received the message).

Interesting to know, MedNet. Did you have a help desk set up for practices that had any problems with installing the PKI? What if the clinician had a hard drive failure or something – is there a recovery mechanism?

MEDNET offers a complete help desk with technical staff and infrastructure support to all of our customers. In the case of a hard drive or server failure, MEDNET has assisted the provider location in restoring secure access for all authorized users in a timely fashion.

It seems you are really confused on the “clinical work” cannot be rationalized into something “linear” method/fallacy.

Humans (clinicians) are flexible and clinical work in high stress situations such as in the ER or ICU, current systems do not allow to help with such workflows.

I’d write more but I’m utterly distracted by the dozen animated advertisements on the left.