Giving a patient medications in the ER, having them pop positive on a test, and then withholding further medications because…

EHR Design Talk with Dr. Rick 3/12/12

Humans Have Limited Working Memory

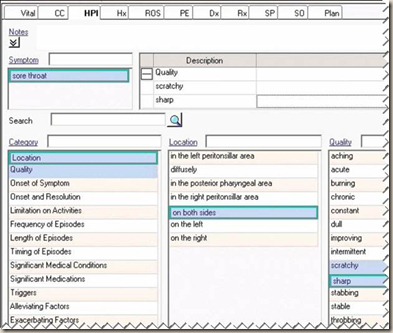

Consider a very common, high-level EHR design. The screenshots that follow are from a particular EHR, but many vendors use a similar design.

A row of clickable tabs at the top of the screen is used to designate the different categories of data that make up the patient visit. When a tab is clicked, the window for that category of data opens to full screen size. The tabs can be clicked in any order.

The screenshot above shows what I would see after having clicked on the History of the Present Illness (HPI) tab and having entered some data.

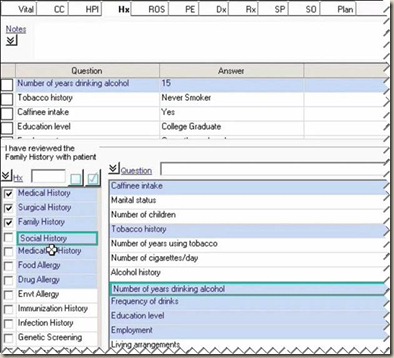

If I were then to click on the History (Hx) tab and enter some data, the new screen would look like the one above. The HPI data is no longer visible because the HPI window automatically closes when the Hx tab is clicked.

This EHR design is completely logical. It is also completely usable, if usability is defined as being able to easily navigate from one part of the record to another with a single click. In fact, it is a totally reasonable design if it weren’t for one problem — humans have absolutely terrible short-term (working) memory.

It used to be thought that humans could retain about seven unrelated elements in working memory, but recent work suggests that the actual number is more often in the range of four to five. In contrast, a modern computer has no problem retaining thousands of unrelated data elements in random access memory.

Given our severe limitation in working memory, this EHR design doesn’t work very well. Every time I click on a new tab, the previous window closes and that data is no longer visible. I have to carry that information in my head. Furthermore, the row of tabs itself contains no information. It just serves as a navigation tool.

In other words, this design is based on how a computer — not a human — thinks. It is a computer-centered, not a user-centered design (see my first post).

As a clinician, I need to devote my full cognitive resources to my patient’s health issues. I need to be able to retrieve information from any part of the record quickly and effortlessly. While completely logical, this very common EHR design just doesn’t do a good job of extending my working memory. From personal experience, I can tell you that using a system like this is enough to drive you crazy.

So what’s the alternative? The alternative is to design an EHR based on what humans are good at — using our visual system to make sense of the world. The data needs to be organized spatially, assigning each module to a fixed location on the screen the way that T-Sheets and other paper forms do (see my previous post). Instead of making the overview of patient data just a row of information-less tabs, display the actual data in a one- or two-screen view, allowing the clinician to see the information rather than forcing him to remember it.

Of course, every design requires compromises. If you decide to use a compact, fixed spatial layout for your high-level design, then you need to solve the twofold problem of what to display in the default view and how to display more information on demand.

In my next post, I will present an example of one widely used EHR design solution to this problem.

Next post:

The Problem with Scrolling

Rick Weinhaus MD practices clinical ophthalmology in the Boston area. He trained at Harvard Medical School, The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and the Neuroscience Unit of the Schepens Eye Research Institute. He writes on how to design simple, powerful, elegant user interfaces for electronic health records (EHRs) by applying our understanding of human perception and cognition. He welcomes your comments and thoughts on this post and on EHR usability issues.

Dr. Weinhaus, I train this EHR. Most docs think it an improvement to paper charting. If you want to see CC/HPI simply click that tab (like turning a page). There are also summary note views, icons and “sliders” for various history displays like allergies, medications, patient demographic, etc. Screen real estate seems to always be the bug-a-boo. Looking forward to seeing your improvement ideas though.

EHR Trainer — Thanks so much for your comment and interest.

For me, the issue is not whether an EHR is an improvement over paper charting (although one could make good arguments for some aspects of both paper and electronic charting), but whether the design of the EHR supports the way that humans best take in, organize, and process information.

You are right that clicking on the Chief Complaint/History of the Present Illness (CC/HPI) tab, for instance, is something like turning a page in a paper chart, but with many EHRs, you would need about eight or ten chart pages just to document and review a single patient visit. A paper chart of this design would soon become unwieldy to the point of being unusable. In other words, the data density on a page in a paper chart is frequently much greater than the data density on an EHR screen.

Furthermore, with a paper chart, you can keep a finger on one page while flipping back and forth to other pages. The physical pages don’t disappear the way that screen data does when you navigate to a new screen.

In my opinion, the summary note views of many EHRs don’t work very well for two reasons. First, many of the categories of data are omitted from these summary views, so you still have to navigate to other screens to get an overview of the patient. Second, you can get a proliferation of different summary views, each showing a slightly different subset of data, without any of the summaries supporting your task at hand.

You are absolutely right that screen real estate is always the issue. The digital solutions for dealing with limited screen real estate are necessarily different from the solutions for packing information densely on a piece of paper. In my next post, I look forward to presenting one widely used solution to this problem — scrolling — for discussion and debate.

Rick

Dear Rick,

I totally agree with your recent posts on EHR usability.

Actually there is one whole chapter on Usability in my forthcoming book which starts along the same lines of thought raised in this post.

A tentative solution to the issue of breaking the clinician’s cognitive process

is offered as well.

If you’d like – please send me your email address and I’ll send you this chapter as a PDF.

Best regards

A. Scarlat MD, Bsc Computer Sciences

Dr. Scarlat,

Thanks so much for your note. I’d like very much to see your chapter. It is very nice to know that you are working on these issues.

My email address related to these posts is:

drrickweinhaus@gmail.com

Rick

Dr. Rick,

I couldn’t agree with you more. Since reading your post on EMR usability I’ve referenced your “tic-tac-toe” example in countless discussions I’ve had with hospital staff all over the country. Admittedly I am a salesman with one of the vendors supporting HISTalk. I frequently share with my colleagues statements like: “clicks count,” “aesthetics matter,” and “individualized usability trumps all.”

More often than not, as demonstrated in the screenshots you provided above, these systems are constructed by engineers who think of clinical encounters within engineering eye. Physicians are not engineers, rather, they are more tacticians then anything else. It is incumbent upon physician’s to review an entire set of challenges globally. Doing so while constrained to the limited amounts of information displayed by the engineer at any one time is at best, frustrating.

I applaud you for your efforts to bring these concerns to light. You’re obviously not the first to hold these opinions, but you’re one of the first I’ve read who can communicate it so effectively.

EMRs and EHRs should indeed be consistent with human abilities. Many disciplines lay claim to this territory, but I’d like to call attention to the human factors sub-discipline within industrial engineering (increasingly called industrial and systems engineering).

An EHR designed and implemented using industrial engineering principles and techniques is a fundamentally different EHR. Instead of starting with a user interface that looks like a paper form, it is derived, using scientific and engineering principles, from the human body’s response to physical, physiological, and cognitive workload. Perception, attention, cognition, motor control, memory storage and retrieval interact with work environment and job demands to result in knowledge about mental workload, vigilance, decision making, skilled performance, human error, human-computer interaction and training.

Resulting EHRs do not look like what has gone before. Computer displays in aircraft cockpits first mimicked physical dials and switches. Today’s “glass cockpits” do not. Many EHR designers are seduced by the idea that since users are already familiar with paper forms that the paper form metaphor is a good user interface. It is not. EHRs that try to mimic traditional paper medical records are not well designed for high-usability, high-productivity data and order entry. Of course, EHRs do still need to generate hard copy and digital forms that resemble traditional medical forms, but this is a different issue.

Many cite Steve Krug’s “Don’t make me think”. Designing EMRs and EHRs that don’t make you think requires a lot of thinking about cognitive science, and not just psychology, but also linguistics, artificial intelligence, anthropology, and even philosophy and neuroscience. Krug gave a presentation several years ago in Toronto, at which was tweeted: “Krug on learning UX: Take an intro to cognitive science course to learn the theory of UX. #uxbcto”

http://twitter.com/chrismendis/status/8258187659

Yes!

I look forward to the rest of your series on designing simple, powerful, elegant user interfaces for EHRs by applying understanding of human perception and cognition (in your simple, powerful, elegant words).

Chuck

P.S. Relevant to your post:

“Don’t require a user to remember things from screen to screen.”

Usability Expert Jakob Nielsen Would Like EMRs/EHRs with Big Targets, Less Functionality and Better Workflow Management

http://ehr.bz/9z

“workflow, by reducing cognitive work of navigating a complex system, makes such structured data entry more usable”

The Cognitive Psychology of EHR/EMR Usability and Workflow

http://ehr.bz/up

“Apply cognitive science to improve the human-computer interface; you get usability engineering”

ostensibly about “usability checklists” (though, to be clear, not checklists within EHRs, which I certainly favor), but also about cognition and design.

The Cognitive Science Behind EMR Usability Checklists

http://ehr.bz/ui (By the way, this short link? Just a coincidence! Really!)

Hi Dr. Weinhaus,

I have read only this article yet, and have opened the other two (you refered to in its text). In the last ten years of designing hospital IS and EMR, I have often come across these issues. It is interesting to note that they are pretty much global. We all are the same humans after all… More interestingly however, I see that the approach of the software developers is also much the same.

Thank you for pointing them out, and I am sure they will help me put across my case better as I am to facilitate a workshop on EMR: Issues and Opportunities, in a fortnite. couldn’t help myself write already, before reading the next two artricles.

Have a good day.

Zaman.

Court Jester and Zaman —

Thanks so much for your comments! It is very gratifying to know that I am not writing in a vacuum. The goal of my posts is to make a contribution to the national (and international) discussion on how to improve EHR design — to contribute to the development of a new healthcare information language, so to speak. Your feedback makes the hard job of trying to conveying my ideas succinctly worth it.

Chuck —

Thanks so much for your comments. You raise many critical design issues.

I agree completely that human factors in general and systems engineering in particular are essential to good EHR design. The question is — are they sufficient?

In my opinion, before applying human factors and systems engineering to EHR design and workflow, the first step is to define the goals, not the tasks, of the clinicians and other users. The second step is to make the high-level design of the EHR user interface conform as closely as possible to the clinician’s mental model of patient care.

I agree with you that in general, most metaphors from the mechanical age do not work very well when replicated digitally. I also agree that specifically, trying to replicate the design of the paper form unchanged in an EHR does not work very well.

I am not suggesting that one should try to exactly replicate the paper form in designing an EHR user interface. The solutions for organizing and displaying patient data digitally are necessarily going to be different from paper-based solutions.

That being said, I would propose that a viable high-level EHR design is to assign each category of data to a fixed location on the screen and to have that single screen provide both an overview and details on demand.

I very much look forward to your continued input as I present some of these design ideas in more detail in future posts.

Rick

Rick

Great insight from a physician. I am curious about your last comment (3/14 @ 8:53 pm) wanting ‘each category of data to a fixed location.’ Are you looking for something to reference quickly during your office visit without having to leave the office visit screen? Most any EMR has this data in the ‘chart’ but this means leaving the office visit to reference the history/data.

I am asking because I sell and EMR and have been involved in building a patient summary template for users to reference within the office visit itself. One page, fixed locations, same data, data updates during the visit, but is for reference only. Once built, I showed some customers and each one said ‘ohhh’ this would help me and my short memory.

Mike —

Thanks for your comment! Yes, I am definitely suggesting a design that presents an overview of all the data categories in a single screen view, with this view representing a snapshot in time of the patient’s health.

Rick

Dr. Weinhaus,

I always enjoy reading your articles. Two comments/thoughts (for disclosure, I do work for a major EHR vendor, though not the one you’ve mocked up in this case):

1. In your example of documenting HPI/Hx/etc., I would say that there are two separate activities being performed by the physician. The first is simply documentation – collecting information and recording it. The second activity is using the collected information to make a clinical decision.

To me, the UI presented is appropriate for the first activity – the collection of information. It’s certainly true that you won’t be able to hold all the pieces of information from another tab in working memory, but if your goal is to simply document the information, in general you wouldn’t need to.

I wholeheartedly agree that this UI is completely inappropriate for the second activity – reviewing the information collected and making a decision based upon it. What would your thoughts be about a hypothetical design that used the exact same UI for collection, and presented the information in a second, summarized form for the purposes of review and decision-making?

2. To what extent do you think the optimal logical organization of information varies from person-to-person? Clearly things such as the capacity of working memory are less variable, but to again go back to your tab-based layout – there’s a new generation that will be highly familiar with this UI, as it’s the fundamental way that a web browser organizes pages. How do you think their experiences will shape the optimal way to format information for them?

An EHR Developer —

Thanks so much for your note! You raise two very interesting issues.

1. We are so used to thinking of collecting and recording information as one task and summarizing and reviewing it as another that we tend to program a separate user interface for each. An alternative design would be to use the same pane for both tasks. For instance, a summary view of the past medical history could be assigned to a pane in a particular location on the screen. For data entry, that same pane could expand to a larger size (but not full screen in order to preserve as much screen layout as possible) and then contract to its summary size afterwards.

A design of this type would reduce the total number of screens and views needed to present the patient data. It would probably be more difficult to write the code for this kind of dual-purpose pane, but the reward would be a simpler user interface.

2. I have been thinking about the tab design as well and why it works for some applications and not others. I think that the difference is that with many websites and applications, the user is looking for a particular piece of information. In this case, tabs can work pretty well.

For instance, you might visit the website of a university to see your team’s basketball schedule or you might visit it to see what a particular faculty member had recently published, but you probably wouldn’t be looking for both pieces of information at the same time.

In contrast, when using an EHR, the clinician is always trying to explore connections between different categories of data. Having the data visible on the same screen facilitates these kinds of open-ended queries.

Rick