RE: Change HC/RansomHub, now that the data is for sale, what is the federal govt. or DOD doing to protect…

Readers Write: The Transition TO Paper Record Keeping

The Transition TO Paper Record Keeping, Featuring the "King of Desks"

By Sam Bierstock, MD, BSEE

With the digital age has come the rejection and vilification of paper. The entire healthcare industry has been on a writhing, agonal path to the adoption of electronic health records for more than a decade.

Have you ever wondered, though, about the transition to paper record keeping?

In a previous historical perspective, I paid tribute to Joseph Lister and his Herculean efforts to convince physicians and hospitals about the need for asepsis – the champion of champions of physician adoption. Compared to today’s challenges with physician adoption of technology, it took Lister almost 20 years to move past ridicule and 30 years to see his arguments fully appreciated and his recommendations put into practice.

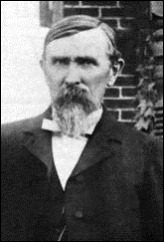

In the world of paper record keeping, another, less well-known 19th century figure deserves recognition – William S. Wooton.

We have been documenting on paper for centuries. It is fascinating to walk through Jerusalem’s Israel Museum and browse through the ancient, centuries-old handwritten documents dealing with issues that persist to this day – contracts of sale, employment, marriage, divorce, debt, inheritance, and all other matters of transaction, discord, and agreement. Record keeping of the day involved rolling documents and wrapping ties of various sorts around the resultant paper cylinder for storage in jugs or other designated compartments. Copies were reproduced by hand. Larger and longer documents were recorded on scrolls that piled up in corners and on tables.

Paper record keeping progressed slowly, the most major advance in printing of course coming as a result of the invention of the paper press by Gutenberg in the mid-15th century. Still, business transactions were maintained in ledgers and entered by hand. Essentially no written records were kept by physicians, even well into the 19th century. Past history and treatments administered were simply left to the physicians’ memory and the strength of physician-patient relationships over time.

In today’s world, we recognize the need for record keeping to maximize our ability to deliver the best possible care, overcome our limited memories, and ever increasingly, to protect ourselves as caregivers from medico-legal vulnerability.

In ancient civilizations, shamans with consistently poor therapeutic results were often dealt with simply and quickly by being killed. Evidently, iatrogenic patterns have been recognized for a very long period of time. Greece, Rome, and later Europe during the Middle Ages were much more forgiving, often having laws in place to provide immunity for misjudgments of doctors. During the Great Plague in the 14th century, almost one-third of England’s population perished, and people began to wonder if it was possible that physicians of the day didn’t actually know what the hell they were doing. But the idea of medical record keeping still did not occupy the concerns of physician for centuries after the Plague.

It is not clear as to when physicians began to understand the need for complete record keeping. I am old enough to remember my own family doctor maintaining my entire record on a set of index cards, and it’s not that long ago that I saw practices where physicians kept the records of an entire family in single file. It is my personal belief that medical note-taking probably became much more prevalent with the availability of the fountain pen, which made the act of writing much less arduous and certainly more portable. Beginning in the middle of the 20th century, we must reluctantly tip our hats to malpractice attorneys who made it painfully obvious to us that we needed to defend our decisions and actions.

The first recorded malpractice case was probably that heard before the court of John Cavendish of the Court of King’s Bench in 1375. A highly regarded surgeon by the name of John Swanlond had treated the crushed and mangled hand of one Agnes of Stratton. The condition of her hand had not improved after a few weeks and the patient consulted a second surgeon, who informed her that Dr. Swanlond’s treatment was deficient. When her hand became severely deformed, she sued Swanlond. Although the suit was voided because of a technical error made by the patient’s lawyer, the judge made the following note in his written opinion: "If a smith undertakes to cure my horse, and the horse is harmed by his negligence or failure to cure in a reasonable time, it is just that he should be liable." This case set the precedent upon which has rested all subsequent Western malpractice litigation.

The first recorded malpractice case in the United States (Cross v. Guthery) was heard in Connecticut shortly before the American Revolution. “When Mrs. Cross complained that there was something wrong with her breast, her husband sent for a doctor named Guthery. The doctor examined Mrs. Cross, diagnosed her ailment as scrofula, and amputated her breast. Shortly after the surgery, Mrs. Cross hemorrhaged to death. Dr. Guthery expressed his regrets to her husband and then sent him a bill for 15 pounds. Cross hired a lawyer, who persuaded a jury to dismiss Dr. Guthery’s bill and award Cross 40 pounds as compensation for the loss of his wife’s companionship."

In the United States, the years following the Civil War began an age of remarkable industrialization and business growth. Until then, most businesses were run by one or two principals, often in the same family. Services were provided directly and most material products were constructed on site. Paperwork requirements were therefore low. Customer interactions were recorded by hand in ledgers, and payment for employment services was generally in coin or via bank draft. After the war ended, enormous growth of commerce combined with technical advances allowed for massive growth of business. White collar workers were needed and their numbers increased at a very rapid rate. At the same time, the first fountain pens and typewriters appeared, as did carbon paper and the first rudimentary copying machines.

Within the space of one or two decades, businesses had a new problem – a lot of paper and a need to keep it filed in an orderly fashion and readily accessible.

William Wooton was born in 1835. He was employed during the 1860s as a furniture maker in Illinois. The idea struck him that if he could build school desk and chairs in a single unit that folded up and could be moved, a classroom could serve multiple purposes, including such activities as both teaching and gymnastics. After obtaining a patent on his design for a foldable school desk and chair assembly, he opened his own furniture-making company in Indianapolis in 1870 and achieved rapid success selling school and church furniture.

As his business grew, he observed his own employees taking and fulfilling orders, and struggling with paperwork strewn about. Wooton then realized that businessmen needed an efficient way to file and keep their ever-growing accumulations of paper organized. From this realization, came his design which ultimately earned him the title "King of Desks" – the Wooton Patent Desk.

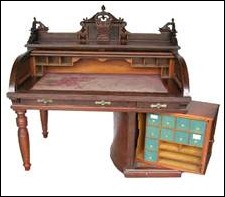

Produced between 1874 and 1885 to 1889 (it is unclear when the actual last desk was produced – some may have been produced into the 1890s), the Wooton Desks were (and are) magnificent pieces of furniture, with 110 compartments for storing documents. Two large swinging doors open to reveal a folded-up desk top, which when lowered, exposes more storage bins. A slot is usually present on the left front of the desk for a built-in mailbox. A horizontal hidden cabinet is present above the desktop for even more paper storage. Wooton also patented and produced a flat desk with pedestals containing rotating sections which contained filing bins and shelves.

The upright Wooton Desk came in four styles: Regular, Standard, Extra and Superior. Although production peaked at one point at 150 desks per month, it is estimated that as few as 12 Superior-grade Wooton desks were produced. Ownership of one of these desks was considered a status symbol and a privilege of the wealthy. They ranged in price from $75 to $750, equivalent of $1,531 to $12,765 in 21st-century dollars. Four US presidents are known to have been Wooton desk owners: Grant, Garfield, Harrison, and McKinley, as well as John D. Rockefeller, Joseph Pulitzer, and railroad magnate and speculator Jay Gould. Queen Victoria also commissioned a Wooton desk. Three are in the possession of the Smithsonian Institute, one being President Grant’s. One of the desks purchased new by the Smithsonian in 1876 has now been in continuous use for 137 years.

William S. Wooton conceived of, designed, patented, and produced the both the Wooton Patent Desk and the Wooton Pedestal “Rotary” Desk between 1872 and 1885. In 1884, he abruptly left his successful company to become a Quaker preacher, leaving the company management to others. Business reversals followed as the company could not keep up with demand, leading to slowed production after 1885 and closure around 1889. Wooton died in 1907 at the age of 72.

I saw my first Wooton Desk in the office of a realtor when I was setting up my practice in 1977 and was instantly smitten. I immediately offered to buy it, but didn’t have the money. Today, I am a proud owner of a Standard style Wooton desk, and find an ultimate irony in placing my laptop on the desk surface. Having spent my professional career advocating the adoption of electronic health record systems and the elimination of paper, beginning almost exactly 100 years after Wooton dedicated his life to maximizing the efficiency of working on paper, the irony seems exceptional. To use a computer on a Wooton desk seems to bring together two completely contradictory forces of history – one representing the ultimate and revolutionary means of its day for controlling paper record keeping, and the other a tool designed as the ultimate solution to the elimination of as much paper as possible.

Original “Standard” style Wooton Desk

“Standard” style Wooton desk with doors open and desktop down

An “Extra” style Wooton desk

A pedestal-style Rotary Wooton Desk

Rare single-pedestal roll-top Wooton Desk

The Ultimate Irony

If anyone is interested in learning more about Wooton desks, please feel free to contact me at samb@championsinhealthcare.com.

Sam Bierstock, MD, BSEE is the founder of Champions in Healthcare, www.championsinhealthcare.com, a widely published author, and popular featured speaker on issues at the forefront of the healthcare industry.

Where are they sold? Beautiful desks. How many do you have? I saw several in the Red Lion Inn in the Berkshires several years back.

I need to organize all of the papers laden with gibberish that are printed because of the user unfriendliness of the EMR.